Antonin Artaud’s The Theatre and The Plague: A Film by Wolfgang Pannek

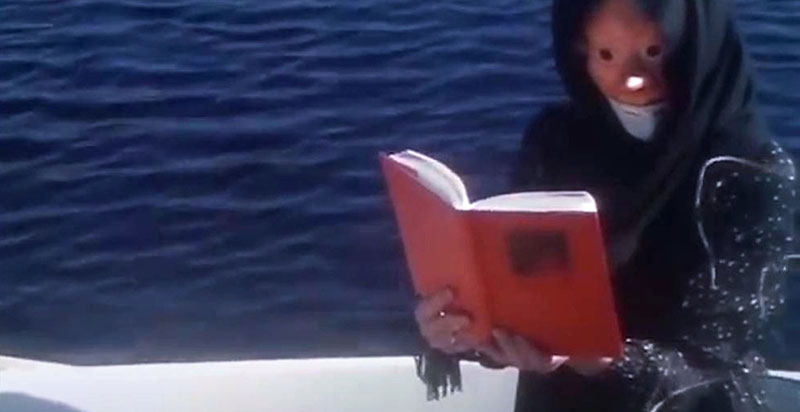

Image: Reha Bliss, “Human Sacrifices”

Antonin Artaud’s The Theatre and The Plague: A Film by Wolfgang Pannek

by Anton Bonnici (Paris, France)

OF all the essays in Antonin Artaud’s seminal collection, Le Théâtre et son double (The Theatre and Its Double, 1938), there is one in particular that leaves an indelible impact not only on its readers but also on the rest of Artaud’s work, its reverberations reaching out to redefine both what came before it and what would come after. This is an essay of such gravity, and such insight into the heart of theatre and the pits of man, that it traces the ambitions at the very limits of all our artistic endeavours.

Artaud draws an unthinkable analogy, sifting through a history of fatal contagions we label as “the plague” and arriving at the eponymous observation that it is here, in the plague’s own ambiguous method of appearance and reappearance, of individual bodily invasion, and of societal terror and collapse, that we may find theatre’s own raison d’être. The plague destroys all that enslaves man in his daily shackles of norms, rules, and constructed realities, all that deprives him of the essential truths found within. Theatre, so Artaud, should act as just this purgatory power, this moment of societal dissolution which allows its witnesses to come face to face with a plane of being otherwise always locked away behind the thick iron curtains of what Artaud calls a society that is unknowingly killing itself.

The essay’s bold observations throw down the gauntlet for future generations of theatre makers, not only challenging their conception of why they make theatre but also challenging them to engage over and over again with Artaud’s text itself, its symbolism, its language, and its uncompromising images and visions. It is this challenge that Wolfgang Pannek has taken up and shared with the international group of performers, artists, and academics that came together in 2020 for their own timely filmic interpretation of “Theatre and the Plague.”

Wolfgang Pannek, “An Imaginary Line”

Keeping to the virtuous tradition of the artist as the poetic voice that addresses the curses of its own day and age, Wolfgang has chosen the ideal text to sink our teeth into whilst the world was literally on pandemic lockdown, fighting the latest “plague,” and we had to rethink not only our methods and means, but also the nature of our work as people whose lives depend on the public space.

Thus was born this project, an audio-visual collection of eighteen cinematic narratives from five continents, each reading a segment of the essay in its own language, all filmed and recorded with whatever resources were available in 2020, some under full lockdown conditions. Once collected, the contributions were re-edited into a full feature film by Wolfgang himself, giving us a complete reading of Artaud’s essay, moving from language to language, country to country, image to image, creating a kaleidoscopic audio-visual interpretation of the text juxtaposed with the all-too-real pandemic conditions experienced by the collective.

Florence de Mèredieu, “Le Grand Saint-Antoine”

The film opens with the segment “Le Grand Saint-Antoine” by Florence de Mèredieu, a sequential collage ranging from obscure domestic environments to historical illustrations and maps of Marseille with superimpositions from F.W. Murnau’s eerie Nosferatu (1922) setting the stage for what will clearly be an unrestrained journey of audio-visual exploration. Yet the full impact of the project dawns on us with the second segment, “Symptoms” by Nabil Chahhed, as we shift from French to Arabic, from Paris to Oueslatia in Tunisia, and the inter-cultural tapestry woven by Wolfgang out of the artists’ individual creative efforts starts to emerge, mimicking Artaud’s own textual meanderings as he attempts to trace the untraceable movements of the plague across civilizations and eras.

Jorge Ndlozy, “The Most Terrible Plague”

The journey is as tumultuous as it is compelling. It takes us from the pale, old face in the dark, reading against cold, Icelandic landscapes in Trausti Ólafsson’s “Magnetic Phenomena” to the strong, dark face of Mozambiquian performer Jorge Ndlozy, reading in Changana and seemingly behind the bars of a sunlit, concrete cell in “The Most Terrible Plague,” and from there to a young girl in a princess costume playing amongst the mausoleums of a Berlin cemetery in “Human Sacrifices” by Reha Bliss. The internal battles and transformations of the plague-ridden body as described by Artaud are turned into a battle of sound and image playing itself out beyond restrictions of geography or age. Young and old, strong and innocent alike become fair game not only for the plague, but also for the symbolism these artists endeavor. The sequence climaxes into one of the most iconic physical performances of the film, by Candelaria Silvestro from Argentina, as her twists and contortions in “The Consciousness” lead up to a harrowing image of a stretched-open face in the bright light of soul-crushing data spewed out of a mobile phone.

Candelaria Silvestro, “The Consciousness”

The cities we inhabit, their spaces under attack by unknown forces, are explored in the segments “An Imaginary Line” by Wolfgang Pannek, showing images of a desolate Paris, and “Tragic Actor remains enclosed within a Perfect Circle” by Or Kittikong from Khon Kaen in Thailand, which ends on the equally mundane and menacing image of an ordinary lock, bringing us face to face with the “lockdown” in a painfully vivid and literal manner. This stark imagery is immediately subverted by the clownish antics of Jürgen Müller-Popken in “Paroxysm.12 / Walk” as he plays with a variety of symbols such as the bell, the tightrope, and the masked figure in a boat, nudging us to disambiguate an apparent freedom that might be enslaved in its own repetitive behaviours. We then move on to Brisbane, Australia, where that most enslaving of domestic technological toys, the flatscreen television, is used to full effect by Shane Pike in “In Splendid Health.”

From the cities, we dive ever further, ever deeper, into archetypal zones of the unconscious. Over the latter half of the film, we watch the artists build a repertoire of performative gestures that break the same social assumptions Artaud grappled with. In “Symbols,” Candelaria Silvestro takes us back to a primordial age of cave paintings and faun-like images, creating a mystical aura which is also evoked by Trausti Ólafsson in “This Contagious Delirium” as religious imagery is pitted against cold video recordings of a liminal space which could only be inhabited by lost souls. A sense of ritual and sacrifice is also explored, this time via fire and fire walking, by Jürgen Müller-Popken and Insa Popken in “Anabella’s Song: ‘It’s not that I cry out of repentance’,” leading to what might be the first liberating image of this fragmented narrative as the clown and the masked figure leave behind the fire and the alarming bell to head out onto the stream in their emblematic boat.

Jürgen Müller-Popken and Insa Popken, “Anabella’s Song: ‘It’s not that I cry out of repentance'”

Our collective search for a way out of the dark is further tapped into, as if instinctively, by Reha Bliss and Théophile Choquet in “Image of Absolute Danger” and “A Superior Notion of the Theatre” respectively. Both exploit the image of the hand tentatively reaching out to open the locked door, one finding a menacing world of bio-chemical terror outside, the other discovering the squirming, vulnerable creature within: two visions of humanity in despair, or possibly a vision of something else, something beyond humanity, a liberated, unknowable horror which is, perhaps, what we have been striving to reach after all.

I am aware that over the course of this review, I have focused more on the visual aspects than on the sonic and linguistic elements of this collection, yet I may bring these into the frame here, on the final step of the journey. As we float, like the clown and the hooded figure on that small boat, down the film’s sonic stream from French to Arabic, from Icelandic to Changana, and as our ears are challenged over and over by eleven languages as well as the novelty and musicality of each new code, we still cannot anticipate the power that assaults us when Maura Baiocchi’s reading of the final segment, “The Question,” reaches our ears in Portuguese.

The immensity of Maura’s drawn-out sibilants and harsh, unvoiced fricatives accompanies us as much as her performance into our final, liminal destination, a place in between places, rural and wild, with an infinite blue sky above, yet also framed in parallel electrical lines stretching above acres of forestry from giant metallic towers, making the presence of the far-off, machine-like city felt even here. Syllable after syllable, our journey is drawn to its conclusion in this impossible landscape upon which Maura inflicts herself in her white dress and flowing hair, embracing the unearthly liminality and reaching out to the sky beyond the electrical fields in an ambition worthy of the theatre as envisioned by Antonin Artaud.

Maura Baiocchi, “The Question”

In its totality, this audio-visual, cinematic reading of “Theatre and the Plague,” as compiled by Wolfgang Pannek, achieves a significance beyond the sum of its parts, moving its viewers into a fresh, contemporary engagement with the text and many of its ramifications. In his essay, Artaud explains how his engagement with the plague forced him to conclude that it was ultimately a “spiritual physiognomy” we are dealing with and not merely a biological one. It is this spiritual physiognomy that truly enraptures us in this film which succeeds in bringing together a collective of performers, artists, and academics in a shared vision beyond the limits assumed by the current state of our world, a vision that invites all of us to a superior notion of the theatre.

Note: A Portuguese version of this review has been published in Agulha Revista de Cultura.

Responses