Albanian Softshoe: Addressing American Issues via the Most Anti-American Country

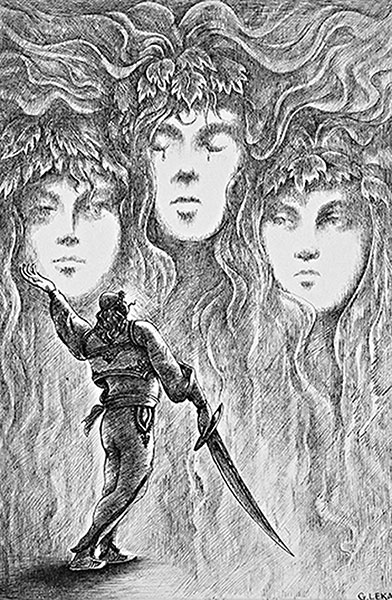

Image: The Children of the Planet Saturn, Jan Brueghel the Younger (1601-1678)

Anxhela Hoxha-Çikopano

Albanian Softshoe: Addressing American Issues via the Most Anti-American Country

In 1985, inspired by a book about Albania, Mac Wellman wrote his play Albanian Softshoe. Not an easy read, the play embodies the theories and practices of poetic theater, an alternative political and linguistic school of playwriting explored by Wellman in his quest to escape the political correctness of mainstream US theater. Fascinated by the strange and foreign culture of Albania, the author uses Albanian Softshoe to create an odd rumination on American issues of belonging. Wellman’s unusual appropriation sparked many questions in me as an Albanian, questions from which arose this piece, written from the point of view of a native Albanian and enriched by an interview with Wellman himself.

IT is not usual to know things about Albania. If you google it, you find a small country in Southeastern Europe, bordering Italy by sea; Montenegro, Kosovo, and North Macedonia by land; and Greece by both. Visually speaking, the Albanian flag, with its big eagle and contrasting colors of black and red, is quite a dramatic, arresting piece. Auditorily speaking, the language is unique in the world and the music strikingly powerful. And while some of you may have succumbed to the urge to google Albania right now, I doubt that many went as far as wondering what sort of culture would naturally produce such dramatic visual and auditory elements. There is one American artist, however, who not only devoted serious research to this question, but also became so inspired by it that he used the codes of this small country’s culture to address the issues of no lesser a land than the United States itself.

My aim here is not to elaborate on the details of Albanian culture, but suffice it to say that it is quite remarkable and unique—so unique, in fact, that it compelled numerous travelers and anthropologists of the early twentieth century to record their impressions of it in books: Milan Šufflay, Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás, Margaret Hasluck, Rose Wilder Lane, and Edith Durham, to name only a few. In 1985, US playwright Mac Wellman was inspired by this literature—as well as Eric Overmyer’s play On the Verge—to address American issues of belonging via Albanian culture as a virtual terra incognita.1 As an Albanian, I found it quite bizarre at first to encounter an American writer appropriating the culture of my country to address American issues of homelessness, corruption, invasion, deception, lying, double-dealing, and nosiness beyond one’s own borders. However, I am pleased to report that at its core, Wellman’s Albanian Softshoe uses its encounter with the other culture to craft a worthy quest for a place, for an object, for the other, and for the inner self.

Albanian Softshoe, a play in two acts, is set in outer space, specifically various locations within the planetary system of Saturn. The first act takes place on Saturn itself, in an American-style living room where things are slightly unusual; the second act takes the audience on a journey from one Saturnian moon to the next—most of them inhabited by frowning, freezing Albanians—in search of an old wizard named Pancake, to whom must be delivered a talismanic cheese. If the first act appears somewhat like a soap opera or sitcom, the second act presents the moons of Saturn as a world of tribes where people live by “customs,” a world of vendettas and blood feuds where every legend has a “terrible” ending, and where nonsense is ritual and therefore to be taken seriously.2 So far, so weird—but why Albanians and Albanian culture?

As Wellman writes in the foreword to his play, he was mesmerized by Albanian music because he had never heard anything like it—hence the title.3 He further elaborates in a newspaper article that other than being deeply impressive, Albanian music was basically used by him as a symbol for something completely remote from and unfamiliar to American culture.4 To Wellman, Albania represents a nation of brigands, one which can never be conquered,5 whether by force, by law,6 or even by well-meaning American tourists. However, despite this essential foreignness, and in a way that remains enticingly puzzling to me, Wellman is able to suggest parallels between seemingly obscure settings such as the Balkan countries of the declining Byzantine Empire and American cultural icons like Richard Nixon, who appears, in Wellman, as a perfect fit for this empire in the 10th or 12th century. So how does Wellman, “an incredible treasury of knowledge from obscure sources,”7 as Linda Yablonsky describes him, explore these political parallels and his theme of indomitability through features of Albanian culture?

In the first act, we encounter Harry and Susan, a seemingly typical American couple of the 80s or 90s. Fatigued by the troubles of everyday life and eager to escape their reality, they constantly transform themselves into other characters, turning from Susan and Harry into Rachel and Fred, then into Ginny and Art. Their neighbors, Nell and Bill (the latter never seen), accept these metamorphoses as a given. The main concern of the first act is Susan’s attempt to deal with the fact that her husband has killed the neighbors’ dog. The more the two talk about the issue, the more problems surface. Toward the end of the act, we are introduced to the Man of Shala, who the women think is a roof repairer. All of a sudden, and in a way that remains inexplicable (at least until the second act), this man kills Harry/Fred/Art, thereby bringing the first act to an end.

The act is written in the style of naturalist drama, drawing on the playwriting principles theoretically outlined by Émile Zola as nouvelle formule: faire vrai, faire grand, and faire simple, with a little twist to alienate it from a totally natural setting and to create symbolic approaches while still keeping track of what Zola claims as a must for a naturalist playwright: “observe the reality closely and render it in a carefully documented way.”8 Although the setting is the milieu of an elegant house, one can find hints of the unusual in it, such as human bones in the fireplace, strange sunny afternoons or nights, and odd nature paintings on the walls; and while the characters, whom naturalist drama views as “determined by the forces of heredity and environment,”9 are stuck in their place, their urge to escape is manifested by the replacement of cars, houses, and even whole identities.

In the first act, Wellman strives for the effect outlined by Raymond Williams: “In high naturalism the lives of the characters have soaked into their environment. […] Moreover, the environment has soaked into the lives. […] It is characteristic that the actions of high naturalism are often struggles against this environment, of attempted extrication from it, and more often than not these fail.”10 This sort of rooting and style creates a deep contrast with the second act, a contrast so unexpected and mind-bending that the attempt to grasp it delivers a shock to the audience. Trying to understand the scenery of the second act, which regularly changes and brings in fresh action and information, turns out to be so challenging to logic and senses that by the end of the first scene, the effect of the murder closing the first act has faded.

In the second act, Nell turns into the Fox Person and, by the end, into an Ora; Susan into Wolfert and, by the end, into the Man Who Married an Ora; and Harry into the Slinking Figure. The only unaltered character, revealing himself step by step, is the Albanian bandit, the Man of Shala. The suburban setting morphs into one of science fiction adventure, replete with extraterrestrials, sinister Albanian characters, and a fairy tale ending in which Wolfert marries an Ora (“no one but him ever saw her”) and “they were very happy.”11

Another significant change between acts is the revelation of the appropriated culture. During the first act, one only notes peculiar elements of Albanian culture such as the costume, the typical gun, the tip of a giant shoe in the closet, the dog breed, the Albanian music, the smelly cheese from the Accursed Mountains, and the news of the Albanian dictator who joined the dead of late. In contrast, the second act dwells in the appropriated culture and limits the American one to mere hints. Here, we float among unknown and unimagined moons in the universe, Saturnian moons that somehow all form part of Albanian soil, marking the territory of this unexplored and unique culture.

This provides the perfect setting for Wellman to develop the particular language that characterizes his plays. Perceiving words as objects, the author attempts, even through his language, to break what he regards as the naturalistic theater of his own time. This sort of theater, according to Wellman, “prefers a lot of talk about emotional facts to the real thing. A denuded, and one might say depraved, journalism of the soul. […] American naturalism, in all its variants, despite its inveterate thieving of popular speech, seems to me basically and deeply anti-linguistic, anti-poetic.”12 In response, Wellman tries to bring the ugliest language possible, linking it to Albanian mythic figures such as Wingfoot, a Drangue (people with little wings under their arms):

WINGFOOT

(With passion)Sky. Yarth. Gods. People.

All such like and kinda am.

All kinda hoohah.

You shall all kinda numerous and diverse hoohah am.

Which was and shall have been.

Boring hoohah and him very intriguing one.

Big one and one colored green.

Yet it will hardly kinda no as be.13

Language aside, it is hard for me to imagine an American public of the late 80s grasping this alien setting, trying to decode imagery it has never encountered before, imagery that cannot be accessed through mere logic. Even for native Albanians, it is sometimes hard to grasp the realities of remote and isolated locales such as Shala and Shoshi, the villages in the northern mountains that are depicted in the play as frozen territories, literally and in time, entangled in an ancient blood feud, and where Americans, compatriots of the very people sitting in the audience, are perceived as ghosts and homeless people. True, the author attempts to warn the audience about what it will experience in the second act: “Anything can happen in the mountains of Albania.”14 Nonetheless, the experience remains a culture shock that can only be digested thanks to its setting on distant moons.

The further the second act develops, the more hostile the lunar inhabitants become toward the foreigners (Americans) passing through the realm in their quest to find Pancake and deliver the talismanic cheese. It is not a coincidence that the author chooses two women as his main characters to traverse the Saturn-Albanian territories: only women can get through unscathed, as the harsh oral customs of the Albanian mountains consider them untouchable. The Man of Shala, whom the audience witnessed killing Harry in the first act, and who was well-disposed and helpful toward the women back then, becomes more and more hostile toward these foreigners now, expressing what the natives think of them: “Homeless. A nation of ghosts.”15 He exposes the true intentions of the visitors—an impossible attempt to steal the treasures of this land, magically protected by Oras (Albanian mythical creatures whose wrath should be feared as they can transform people into rocks).

These otherworldly realities help to explain to the audience the mockery and disdain the Albanians—this small, irrelevant people of tribes—show toward the powerful Americans. This country of brigands does not fear them, as it has never feared foreigners throughout its history. The Albanians simply view and judge the Americans as distant people who do not correctly understand how life and the world work—it is customs that make things run smoothly; customs provide the logic for every human action. How can Americans not understand such an obvious thing?

Wellman leaves nothing to chance. The neighbors’ dog killed by Harry in the first act will surface again and the Man of Shala will kill the Slinking Figure to avenge the dog’s life, as required by the oral law of the Albanian mountains. The Slinking Figure, of course, is played by the same actor who plays Harry in the first act, thereby getting killed for the second time by the Man of Shala, who fully justifies the killing in an Albanian cultural context, now decoded for the benefit of an ignorant audience. Wellman explores the culture clash by confronting the Man of Shala with an American character—the Wolf—to discuss the murder. The Albanian looks cruel to the American: he killed a man without even stealing his possessions or his gun. But to the Albanian culture as appropriated by Wellman, the killing is not personal but a matter of honor. Nothing belonging to the dead should be touched because the killing is ritual and, even though this is a country of brigands, not a matter of seizing money or whatever else the dead has on him. The dialogue between the two characters on this point shows how diverse the countries may be in which America involves itself, and how one cannot bring them around to the American way of perceiving and doing things. Therefore, ultimately, these places remain unconquerable in all possible ways.

A cameo, yet a well-placed one for Wellman to show how his compatriots storm into territories they shouldn’t, is played by the American Farmer—a typical, dissatisfied American who enjoys privileges and freedom in the newfound territories where Americans are trying to find solace after escaping their own lands, but who does not appreciate what he has found. The zeal of such foreigners to grab whatever they can is further highlighted by the Albanian Socialist who tells a story of state gold looted by the Nazis, gold which should have been returned to its country of origin but never was. An Albanian audience might have doubted the factual accuracy of this story, but other audiences are unlikely to get hung up on that, rather following the thematic line of going someplace and taking what does not belong to you.

As Marjorie Perloff writes, “Wellman’s teachings are never the obvious lessons, he does not belong to ‘false moralism’ and to political correctness and uses the actual people to discuss major political issues.”16 An uncomfortable fit with both the political correctness of the Right (to cite Wellman: it is almost literally the air we breathe, and there is no doubt that the air is poisoned) and the political correctness of the cultural Left,17 Wellman does not use American figures to bring across his points, but a menagerie of Albanian historic figures, including Enver Hoxha (1908-1985), the former King Zog of Albania (1895-1961), Skanderbeg (1405-1468), and the much-debated Mehmet Shehu (1913-1981), a former Albanian premier who supposedly shot himself but is rumored to have been killed by Hoxha.18 Pancake’s speech toward the end of the play might sound messy and nonchronological to a native Albanian with a grasp of the country’s history, yet the speech still fascinates with its tidbits of truth, making it real and surreal at the same time, once again showcasing the deftness with which Wellman draws parallels between the politics of the United States and the history of other countries.

But let me return to the questions Albanian Softshoe originally raised for me. First, in 1985—the year Wellman wrote the play—Durham’s Albania, which inspired and animated Wellman, was no more. It had been politically and culturally transformed by Hoxha’s communist regime, in power since 1944. The kinship system and other cultural elements that charmed anthropologists and Wellman alike were gone. When I confronted Wellman with this fact, he claimed that when he wrote the play, he was unaware that the communist regime had dramatically and tragically attempted to reengineer most aspects of Albanian culture. The Albania he had found in books such as Durham’s had fascinated him—and, it would appear, still fascinates him—so much that he was compelled to make use of it regardless of its historical actuality. Durham’s Albania offered him the perfect foil for the United States—a country pretending to be something it was not, getting involved in wars such as Vietnam that were not for it to fight, claiming to be the “good guy” of the world while suffering from internal corruption. Wellman’s aim was to confront Americans with the culture of a nation that is never and will never be conquered, imbuing them with respect and consideration for the reality of others.19

Another aspect of Albanian Softshoe that struck me as extremely bizarre was how an American could address American issues by using the culture of a country that, at the time the play was written, was considered to be among the most anti-American countries in the world.20 When I brought this point to Wellman’s attention, he was immensely amused and said that, despite him not being fully aware of this at the time of writing, it was actually a very good thing since it spoke to the cultural contrast he was hoping to highlight.21 Nonetheless, Wellman also claimed that despite his absolute fascination with Albanian culture and his conviction that it belonged in his play, he was unsure if an American company would be able to understand and produce it. According to him, when the San Diego Repertory decided to host the play’s first production, the public did not fully grasp it. But Kenneth Herman, an LA critic, enjoyed it,22 and by deconstructing it in print, created a buzz around the play.

To be fair, Albanian Softshoe is not an easily digestible piece. Its style of poetic theater stands in contrast to the mainstream culture equally animating the two major political forces in the United States, a culture which, according to Wellman, only produces “geezer theater”—an outdated, academic, naturalistic theater that utterly fails at the political position theater needs to take. To construct his poetic theater, Wellman purposefully adopts disorienting features such as the Man of Shala, blood feuds, Albanian music, and stories of Oras and other powerful folkloric creatures, features that cannot be contextualized anywhere else than in the old Balkan mountains. His appropriation of Albanian culture helps him escape “the false moralism of American theater […], the Broadway regional sausage machines or what passes for earnest, politically committed theater downtown in New York or other supposedly sophisticated places, like San Francisco or the Twin Cities.”23 The resulting play is seriously silly yet silly in a serious way, aims at keeping audiences engaged,24 and offers them insights into themselves and their world that might be unavailable otherwise.25

As for my own investigation, when I decided to write it, it was in an odd state of mind, full of questions. How could an author from a gargantuan country like the United States appropriate the cultural codes of a tiny, distant country like Albania to address issues at home? How could an American use the culture of a country that, at the time, was described as the most anti-American country in the world? How could one appropriate a culture that (almost) did not exist anymore? And how could one use a culture without being able to conduct field research on it, since, at the time, Albania was virtually isolated and impossible to access?

My quest through Wellman’s strange universe quenched my thirst for understanding. Albanian Softshoe is the opposite of a cheesy, exoticizing play in which some American hack pilfers your music, your folklore, and your stories to produce a sensational show with no real core. To the contrary, I am now convinced that Wellman’s play offers an excellent example of cultural appropriation with the goal of offering a novel perspective on oneself, in this case the American self. Rather than a larger culture preying on a smaller one, American Softshoe offers an example of intertwining cultures, and I cannot help but agree with Wellman when he writes that “despite its oddities, Albanian Softshoe is one of my best plays (or because of them).”26

“Muji and Oras” by Gazmend Leka, originally published in Ancient Albanian Tales (1987), reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

ANXHELA HOXHA-ÇIKOPANO is a theater scholar at the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and the Study of Arts, Academy of Albanian Studies, Tirana, Albania. She has most recently published a monograph on Customary Law Codes in the Albanian Drama (Morava, 2020) and is currently preparing a book on the so-called Albanian Revisionist Theater, part of the movement of socialist realism during the country’s communist period.

dePICTions volume 2 (2022): U.S. vs. … (Un-)American Crossings and Appropriations

1. Mac Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” in Cellophane, Maryland: PAJ books, 2001, 17.↑

2. Dan Sullivan, “Stage Review: Wellman’s ‘Albanian Softshoe’ Taps Into Another Language,” Los Angeles Times, 22 September 1989 [28 December 2021].↑

3. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 17.↑

4. Kenneth Herman, “San Diego Repertory’s Space Odyssey Looks to Albania for Musical Inspiration,” Los Angeles Times, 14 September 1989 [28 December 2021].↑

5. Kenneth Herman, “San Diego Repertory’s Space Odyssey.”↑

6. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 17-18.↑

7. Mac Wellman and Linda Yablonsky, “Mac Wellman,” BOMB 53 (Fall 1995), 53.↑

8. Austin E. Quigley, The Modern Stage and Other Worlds, Oxford: Routledge, 1985, 285.↑

9. Quigley, The Modern Stage, 285.↑

10. Raymond Williams, “Social Environment and Theatrical Environment: The Case of English Naturalism,” in Marie Axton and Raymond Williams (eds.), English Drama, Forms and Development: Essays in Honour of Muriel Clara Bradbrook, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, 217.↑

11. Marjorie Perloff, “Foreword,” in Cellophane, xiii.↑

12. Wellman and Yablonsky, “Mac Wellman,” 51.↑

13. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 47.↑

14. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 43.↑

15. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 55.↑

16. Perloff, “Foreword,” xi.↑

17. Mac Wellman, “A Chrestomathy of 22 Answers to 22 Wholly Unaskable & Unrelated Questions Concerning Political & Poetic Theater,” in Cellophane, 12.↑

18. David Brand, “Land of Fear,” The Wall Street Journal, 6 June 1985 [28 February 2021].↑

19. Interview with Mac Wellman, conducted by the author for this article on 12 October 2021.↑

20. I turn here to Enver Hoxha to offer just one illustration of Albanian hostility toward anything American from a myriad of such: “We are not for opening our doors to American spies, to decadent art and the American way of life. No, we are not for this road. With our ideology, we should fight all the manoeuvers and condemn the plans and the line of reconciliation with bourgeois ideology. Imperialism aims at destroying our countries not only by means of violence, but also by means of its ideology, its theater, its music, its ballet, its press and television, etc. We do not understand coexistence as the propagation of the American way of life. We do not approve of Czech or Soviet officials giving receptions and dances à la Americana in their embassies. The comrades representing our country abroad have been scandalized by such manifestations. We are not for such a road.” Enver Hoxha, “The Defense of the Marxist-Leninist Line is Vital for Our Party and People and for International Communism,” 7 September 1960 [22 February 2022].↑

21. Interview with Mac Wellman.↑

22. Interview with Mac Wellman.↑

23. Wellman, “A Chrestomathy,” 11.↑

24. Wellman, “A Chrestomathy,” 9-10.↑

25. Wellman, “A Chrestomathy,” 16.↑

26. Wellman, “Albanian Softshoe,” 17-18.↑

Responses