Wallace Fountains: A Model for Post-Pandemic Action

Barbara Lambesis

Wallace Fountains: A Model for Post-Pandemic Action

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 will be remembered as a worldwide health crisis that caused rampant illness, death, economic disruption and severe public health measures to combat its spread. Social, political and economic issues stemming from or exacerbated by the pandemic will prove challenging for governments and non-government organizations dealing with the aftermath. Can the Wallace Fountains of Paris serve as a model for developing solutions to the human needs created by the crisis? This essay suggests they can. It argues for a holistic approach to addressing needs and calls for philanthropy in the spirit of Richard Wallace.

IN 1870, Paris was under siege during the Franco-Prussian War. Residents trapped in Paris suffered terribly from cold, starvation, disease, and terror. Relentless artillery shelling during the war and destruction from the civil disturbances of the Commune period, which immediately followed, damaged much of the Paris water supply system. This left many, mostly the poor and disadvantaged, without access to affordable, safe drinking water. To solve the problem, Paris installed its first public drinking water fountains, conceived and made possible by a wealthy Englishman who donated them to the city. This remarkable public/private effort proved to be a novel solution to a problem created by a crisis and it addressed meeting an essential human need in a holistic way.

Now, we are in an era when Paris and much of the world has felt under siege by the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 and subsequent lockdowns. Pressing human needs will emerge as a result of this crisis. Can the famous Wallace drinking fountains of Paris serve as a model for finding solutions to human needs stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic?

The Story Behind the Drinking Fountains

Water is the essence of human life on earth. Most people take it for granted. Water is perhaps the most important substance on the planet. It is in every living thing. 60% of the human adult body is comprised of water and like most living organisms, it cannot survive without water. Along with being a life-giving substance, water also has been associated with disease, drought, deprivation, natural disasters, economic activity, and human conflict.

Paris, like many great cities, is located on a freshwater river. The original inhabitants of Paris, the Parisii tribe, settled on an island in the middle of the Seine River more than 2,000 years ago. Since then, the Seine has provided access to water for human and domestic animal consumption, for agriculture, and for transportation and trading. Water from the river was fundamental to the growth and prosperity of Paris.1 By the 17th century, this small island community had become the capital of Europe and soon Paris would be called the “Queen of the World.” The city was the trendsetter for style and fashion. People came from all over Europe to observe and bring home the latest fashion, furnishings, and innovations found in Paris.2

Paris also was the first European city to have sidewalks, designated pedestrian paths.3 Sidewalks, along with wide unobstructed bridges, large public parks and grand boulevards, had everyone, including the elite social classes, walking the city for the pleasure of it. No one could see what fashionable ladies and gentlemen were wearing if they remained in their carriages. So, strolling on the sidewalks and in public squares became a way to display one’s style and fashion and to “see and be seen.”

Public sidewalks were the first, and probably only, real social leveler in Paris. All had access to the sidewalks, and everyone who used them had to exhibit a certain degree of tolerance for those outside their social class. Beggars, pickpockets, peddlers, merchants, the bourgeoisie, the elite, the poor, the working class, and the homeless all shared the Paris sidewalk, as they still do today.

In 1870, Paris came under siege during the Franco-Prussian War, which was similar to but far worse than today’s pandemic lockdown. Citizens were cut off and isolated within the city. They suffered from property destruction, deprivation, and despair, but especially from hunger.4

It was Richard Wallace, an Englishman raised in Paris, who came to the rescue. Wallace was the illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess of Hertford, a man of enormous wealth. When Hertford died in August 1870, just weeks before the siege, he unexpectedly left most of his wealth to Wallace. Wallace put it to good use.5

Richard Wallace was always a generous man with sympathy for the hardships of the poor. During the siege, he took to the sidewalks. Walking from district town hall to district town hall, he left behind large envelopes of banknotes for distribution to the poor to use for food, fuel, and healthcare. He set up field hospitals for French soldiers and for British nationals who remained in Paris. In four months, it was estimated he donated the enormous sum of more than 2.5 million francs for the welfare of Paris residents.6

His generosity and aid to Parisians continued after the war and the end of the Commune era in May 1871. He gave money to provide housing for poor families whose living quarters were destroyed by the artillery shelling and food to the kitchens of public hospitals. Destruction to the water supply system got his attention as Wallace witnessed first-hand the alcoholism and disease that prevailed among the poor and working class for lack of an affordable source of clean drinking water.

As the water supply was being restored and the system upgraded after the war, running water to all buildings was not in place. Water delivery was moving toward a subscription system, and richer areas of the city were first to get service. Poor neighborhoods lacked access to affordable, clean water. Most of their water was drawn from the Seine and delivered by carts. Water from the Seine at the time was contaminated, and sickness from drinking dirty water was commonplace.

For many, it was cheaper and safer to drink wine and beer. Excessive drinking also was a habit acquired by many men conscripted from the working class to serve in the national guard during the siege. Guardsmen idled their time in bars and bistros and often went home drunk every night. In addition, workers and the lower class were forced to find housing on the outskirts of the city because Haussmann’s work in central Paris drove up rents. Once the disturbances were over and life resumed, it was a long walk for many to and from work, and bistros were the only place to get refreshment along the way.7 As a result, alcoholism among the poor and working class was rampant and the resulting health and social consequences severe.

Wallace thought it was a moral duty to prevent alcoholism and its damage to the social fabric. One way to do that was to give everyone access to clean water through public drinking fountains on the sidewalks. Thus, Wallace proposed to donate fifty drinking fountains if the city would install them. This project was one of first noted public-private, international efforts to address an essential human need. The fountains were an enormous success as reported by the local press which printed illustrations and referred to them as fontaines Wallace.8 They soon became known by everyone simply as les Wallaces.

Wallace Fountains Were an Exceptional Solution

Richard Wallace had a unique vision for the drinking fountains. From inception, they were to be more than a water spigot. Wallace was an art connoisseur and collector with an interest in the Renaissance, in allegory, and in the classics. His vision for the fountains was beyond the practical function of delivering fresh water to quench the thirst of people on the street. Many considerations went into their final design.

First, the fountains were to be placed on the sidewalks and in small public squares so access to the water was available to everyone. Since all humans require water, all would have the right to use the fountains, rich and poor alike. This was in keeping with the philosophy of egalitarianism.

Second, the fountains were to be monumental in size, almost three metres tall, so they could be easily found. They were to be visually appealing and beautiful, but also blend into the streetscape. They were painted green in keeping with Napoleon III’s Second Empire efforts to bring nature into the city and also to match other street fixtures such as newspaper kiosks and Morris columns.

Third, the latest technology and industrial advancements paved the way for the fountains. A relatively new ornamental cast iron process was used and it made manufacturing the fountains affordable. The process of manufacturing art and decorative cast iron pieces of high quality was developed in France by Jean-Pierre-Victor André who founded the Val d’Osne foundry where the fountains were made. His process allowed intricate, sculptural design to be mass produced. In addition, cast iron was durable and long lasting, which was an important criterion Wallace established for the fountains’ design.

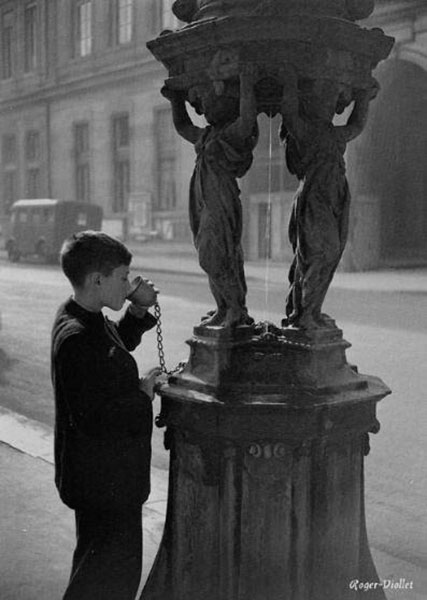

Fourth, assuring a safe supply of clean water was essential. Wallace fountains were for human use only. To prevent stagnation and contamination, a steady stream of water flowed from the top of the dome into a raised basin. Raised basins prevented dogs from using the fountains, and the positioning of the caryatids made it impossible for horses to drink from the basin. Two tin drinking goblets for common use were attached by chains to the fountains. It was customary to leave the goblet in the stream of water after use so it could be rinsed. For public hygiene, the common drinking cups were removed in 1952.

Fifth, Wallace also wanted the fountains to be artistic and beautiful. Just as people bring art into a room to enhance its atmosphere, the fountains were meant to enhance their outdoor surroundings. Artistry was a critical element in the design of the fountains. Richard Wallace drew the original sketches of the fountains and gave them to the well-known and respected sculptor, Charles A. Lebourg. Lebourg refined the drawings and created the final sculpture from which casting molds were made. Wallace firmly believed art could educate taste and expand knowledge. As the Industrial Revolution moved forward, Wallace believed access to fine art would benefit skilled artisans and the general public and help encourage good design in mass produced, ordinary objects. His fountains were an example of this concept.

Finally, Wallace intended the fountains to be inspirational and symbolic. He recognized the complexity of the human condition and realized addressing a specific, essential human need required a solution that speaks to the whole of one’s humanity. He believed art, beauty, symbolism, and sensitivity to the environment can and should be incorporated into practical design. His fountains should speak to the human spirit as well as quench thirst.

Toward that end, he incorporated into the design four caryatids, classic Greco-Roman female figures used as columns to hold up a dome or entablature. Each figure is slightly different and each represents a human virtue: kindness, generosity, simplicity, sobriety.

Other symbols found on the fountains pertain to water and come from mythology and Christianity. On the base pedestal are found tridents, water serpents, scallop shells, and pearls. On the top of the dome are stylized dolphins, which are thought to be the protectors of all things related to water.

Wallace Fountains have been around Paris for almost 150 years and are cherished icons of the streetscape. They endure not only because of the lasting material from which they are manufactured, but because mankind needs tangible monuments and objects like the fountains to also express the other essential things of life–those things the Little Prince tells us are invisible to the eyes. As they dispense water, the fountains constantly remind mankind to be kind and generous, to look for simple truths, and to approach life with sobriety so we can do our best.

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Future

When life returns to “normal” post pandemic, no one can predict how humans will behave. Most likely, the suffering caused by the lockdown, widespread illness, loss of life, and loss of livelihood will be psychological and emotional for most people. Government policies in response to the pandemic temporarily affected the way individuals and families gather, communicate, work, socialize, and travel, and they could result in long-term changes to the way people lead their lives. What new fears and behaviors people will adopt after months of dealing with the pandemic is yet to be determined. For example, once people are free to move about, will they feel comfortable using any public amenities like drinking fountains, children’s playground equipment, public benches, and park chairs? Or will some see every surface originally designed for common use as a repository of germs and source of contagion?

After decades of public education about the reliability of the Paris water supply, skepticism among residents and visitors still remained about the purity of city water. Will the pandemic add to misconceptions and irrational fears about the safety of the water and further discourage people from using public fountains or drinking city tap water?

Moreover, during the lockdown the environment received a break from human assault and significantly benefitted from the reduction of human activity. Air quality in the city improved dramatically and less trash and debris cluttered the streets. Will Parisians acknowledge these improvements and become more environmentally conscious post pandemic? For example, will residents reduce the use of cars within the Boulevard Périphérique? Will working from home become a norm? Will people fill a permanent water bottle at the fountains and stop buying water in throw-away plastic bottles?

What Can Be Learned from the Wallace Fountains?

At the time of publication, it is too early to know all the pressing human needs that might present themselves as a result of this pandemic and government actions responding to it. We know there will be many, and that some people will suffer more than others. If history holds true, those with the greatest needs are more likely to be among the poor, disadvantaged, and the working class where existing social, health, and poverty problems were exacerbated by the pandemic. Some of these needs will be essential, like food, housing, and economic recovery. Others will relate to mental health issues such as delayed educational development, depression, substance abuse, and domestic violence. Whatever they are, the example of the Wallace Fountains should be used as a model for finding lasting, comprehensive solutions to recovery.

Taking a holistic approach to problem solving, just as Wallace did with his fountains, may prove to be an enlightened methodology. Wallace incorporated new technology and industrial advances. He was sensitive to the environment. Art and symbolism were important to the design, allowing the fountains to quench the thirst of the spirit as well as the thirst of the body. The fountains were large so they could easily be found, but also so they could remind us of our responsibility to others. They were philosophically egalitarian, serving rich and poor equally. Today, Wallace Fountains continue to beautify the city in a typical Parisian way–serving the practical need for a drink of water with style, artistry, symbolism, a nod to the past, and a sense of monumentality and egalitarianism.

We know, for example, many will be economically devastated by this current crisis, but their human needs will not be entirely met if they are just given a box of food and a rent voucher. We also must do something to recognize loss and restore dignity, optimism, and hope for the future. The psychological and spiritual side of humans also must be addressed as we inch away from this crisis. Restoring a sense of community in neighborhoods where residents have lost their jobs and small businesses have suffered may require government relief, but it also requires empathy among neighbors and active support for the small enterprises that make a neighborhood vibrant, for example by patronizing the independent bookstores, cafes, boutiques, and services hard hit by the policies used to control the spread of the pandemic.

Finally, the enormously rich also must take a signal from Richard Wallace and see this crisis as an opportunity to step up and use some of their vast wealth for the common good in truly meaningful ways. Private wealth often can be quickly and directly utilized to address human suffering, and in partnership with governments and non-profit organizations can provide a more rapid response to pressing human needs stemming from a crisis. In essence, as we move forward into what is likely to be a different world post pandemic, the public and private sectors must join together to find solutions to the human needs that will emerge from the pandemic and give our communities around the world holistic solutions that are in essence the equivalent of the Wallace Fountains.

BARBARA LAMBESIS is President of La Société des Fontaines Wallace and author of the bilingual guidebook Find the Wallace Fountains Find Paris. She lives part-time in Paris, where she pursues her interests in European history and heritage. A retired entrepreneur, Barbara’s primary home is in Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

blambesis@wallacefountains.org

dePICTions volume 1 (2021): Pandemic Times

1. Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris, New York: Vintage Books, 2004, 2.↑

2. Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City, New York-London: Bloomsbury, 2015, 115-116.↑

3. DeJean, How Paris Became Paris, 30.↑

4. Alistair Horne, The Fall of Paris: The Siege and The Commune 1870-71, London: Penguin Books, 2007, 176-186.↑

5. Suzanne Higgott, Sir Richard Wallace: Connoisseur, Collector & Philanthropist, London: The Wallace Collection, 2018, 35.↑

6. Horne, The Fall of Paris, 167.↑

7. Coline Lorang, “Les fontaines Wallace (1872-2012) : hygiène, esthétique et patrimoine,” Sociétés & Représentations, 34 (2012/2), 215-216.↑

8. The first Wallace fountain was installed on Boulevard de la Villette on July 30, 1872. On August 2, Le Recall wrote of “Wallace fountains.” La Petite Presse used the term “drinking fountain” on August 10, but used the term “Wallace fountain” beginning on August 31. L’Illustration Journal Universel referred to them as “Fontaines-Wallace” on August 17, 1872.↑

Responses