Dispatches: Performance in the Time of a Pandemic

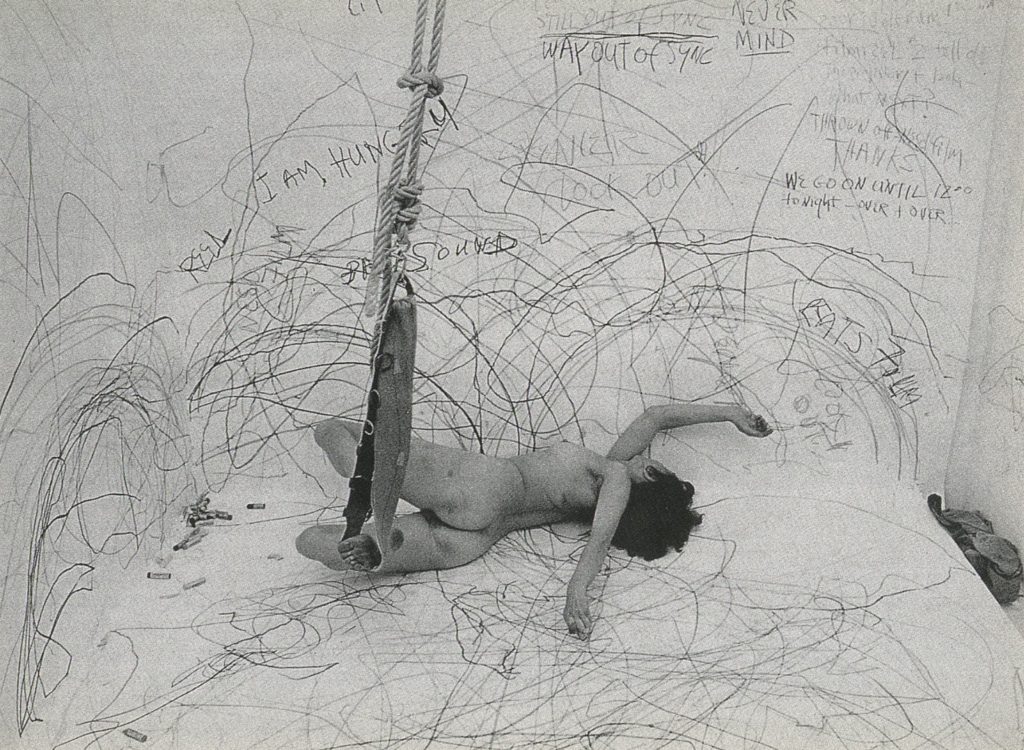

Image: Carolee Schneemann, Up To And Including Her Limits (1973-76)

by Jeanette Joy Harris (Texas, USA)

COVID-19 has dramatically affected cultural life. Museums, galleries, theaters, and performance spaces were forced to shutter, postponing projects in process and canceling others altogether. This closure caused an incredible creative and financial strain on performance practitioners whose work involves public engagement and collaboration with colleagues. Though many dance companies, theater troupes, and musical groups quickly and successfully pivoted to an online platform, other organizations did not have the technical resources to make the dramatic shift from in-person to online. Others decided that virtual performance did not accommodate the type of work they wanted to create and produce.

Should performance practices embrace the virtual world even if gasps, laughs, and applause are replaced by the white noise of muted microphones? Does the possibility of an online platform allow for a new type of audience whose geographic reach is virtually limitless?

Marlène Ramírez-Cancio, Executive Director of EMERGENYC, a vanguard training program and support network for emerging artists in New York City, faced these very questions. Since 2008, EMERGENYC has selected a cohort of up to 24 artists-activists, most of whom identify as BIPOC, women, and/or LGBTIA2s+, to participate in a three-month long, in-person program. The cohort typically meets weekly, and the artists immerse themselves in a challenging and supportive environment where they engage with multiple lineages and approaches to making art. But the pandemic forced Ramírez-Cancio to reconsider how the program could meet its goals of support and solidarity in a time of uncertainty and isolation. The pandemic also forced EMERGENYC artists to consider if it was possible for their work to thrive in a virtual environment.

Ramírez-Cancio and EMERGENYC artists share their experiences in regard to their practice during the pandemic.

Marlène Ramírez-Cancio, “Chancletazo for Your Soul: Latinx Major Arcana.” Image courtesy of artist.

Executive Director, EMERGENYC (Brooklyn, NY)

How did the pandemic affect your practice?

My private Tarot practice was transformed into Mujer Que Pregunta during the pandemic, when I began offering readings on Zoom to BIPOC artists and cultural workers. The lockdown, paradoxically, opened me up to an entire world of transformative conversations. During my Tarot readings, I found myself incorporating Latinx icons and cultural references into card meanings, especially the Major Arcana. So, I decided to make a set of Major Arcana with those icons in it and was asked to be the Artist in Residence at the Aster(ix) Journal as a result. #ThePandemicMadeMeDoIt.

Writer, director, artist, and performer (Brooklyn, NY)

How did the pandemic affect your practice?

It has made me more committed to investing artistry into the documentation of all my art—from performance to visual art. I’ve experimented with this in the past, but I feel it most with the performance. I never want to just drop a single camera down for bare-minimum documentation ever again. It’s not just a record or an opportunity to add texture to the piece, but because film is more accessible, I want the work to reach the audience with as much impact as the format allows.

Writer, director, and performance artist (Bronx, NY)

How did the pandemic affect your practice?

My creative practice centers on excavation, insofar as I am always thinking about the body as a breathing, living archive of stories. The pandemic, in all its terror, forced my body to be introspective of its mortal database and confront the historical traumas that exist in its bones because of colonialism, imperialism, and oppression. In this reflection, I have found softer and more loving narratives in my archive that my previous work only skimmed.

Artist (Brooklyn, NY)

How did the pandemic affect your practice?

When New York was mandated to shelter in place, it felt essential for me to create a space to find a virtual community and make art—it’s what I needed. My art collective created Shared Process, a free weekly workshop in which participants were given filmmaking tools, along with prompts, to document and share their emotional journeys through this bewildering time. This six-week process kept me accountable to making art, which kept me grounded in my purpose and identity.

Visual performance artist, retired contemporary dancer, Iyengar yoga teacher trainee (New York/Oakland/Chicago)

How did the pandemic affect your practice?

Before the pandemic, I explored the subtleties of the changes of the body by making temporary human-object sculptures and tasks during a live performance. During the pandemic, with the prevalence of Zoom as a performance platform that opened up cost effective ways to present multiple perspectives online, I began incorporating video into live online performances. The cameras that I set up to stream content out to viewers’ eyes enabled me to take a directorial approach to presenting the objects within my space while changing and adopting various utilities.

Responses