Gender, Sex, and Printing Press in Ottoman Constantinople

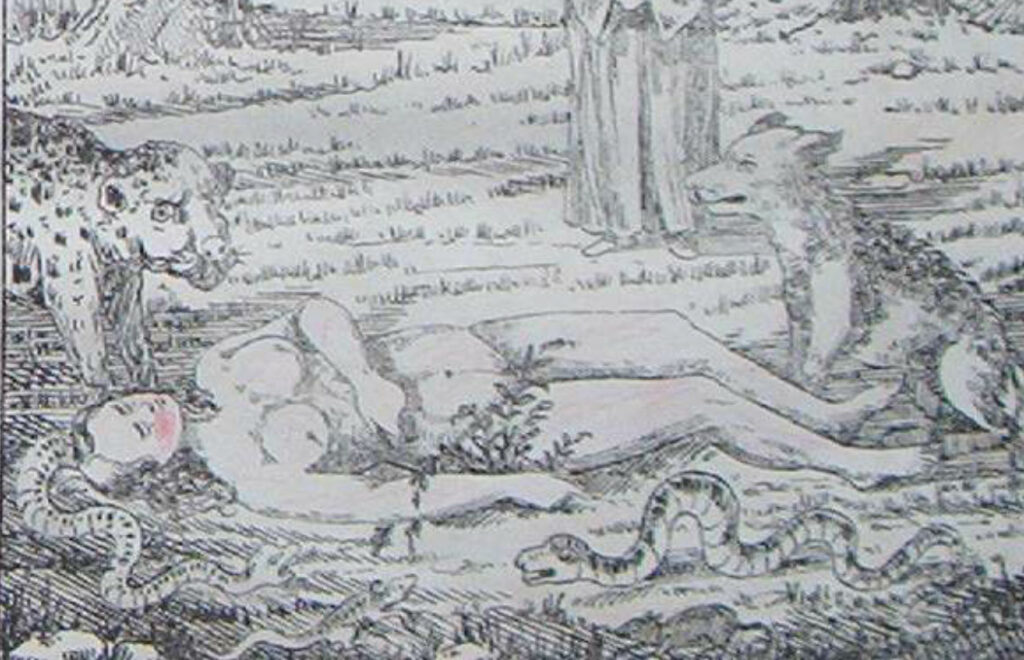

Image from Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi (1851-52)

Gender, Sex, and Printing Press in Ottoman Constantinople

by David Selim Sayers (Paris, France)

EVER since learning Ottoman Turkish nearly twenty years ago, I have been beguiled by the gender world of Ottoman Constantinople1 and the complete alternative it offered to everything I thought I knew about gender up to that point. In 2017, I published a study of this world based on its depiction in the Tifli Stories, a particular genre of Ottoman popular fiction. My goal was to give an outline of urban gender culture as it existed roughly from the 16th to the 18th century, that is, before the Ottomans started engaging with 19th-century Western ideas.2

Ironically, though, most of my sources themselves were from the 19th century, and they had as much to say about the changes in that era as about the status quo ante. So, following my 2017 article, I gave a number of talks3 and courses in which I used the Tifli Stories to explore these changes, and particularly how they had been expressed and promoted through different print technologies. The piece you are reading now is the outcome of these occasions; if it leaves you curious for more, you can read the 2017 article here.

Interpretations of Change

If there is a poster child for the gender world of Ottoman Constantinople before the 19th century, it has to be the boy-beloved. Appearing in all sorts of sources from court records to poetry, he is a refined, witty, and pretty boy, usually of humble origins, who serves, in urban culture, as a universal object of desire. Pursued by women and men, elders and peers, wealthy and poor alike, he points to an understanding of desire that transcends not only boundaries of social status, but also of gender and age. Bartering sexual favors, chasing after prostitutes4 and odalisques,5 and provoking the most brazen disputes, he points to an understanding of sexuality that is hard to reconcile with today’s notions of romance, respect, and taboo. In brief, the boy-beloved and his gender world offer us many challenges, not all of them, I imagine, equally welcome.6

The boy-beloved with older men (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

This feeling of discomfort and unease is nothing new. In Constantinople itself, it surfaced in the 19th century, when intellectual elites who engaged with the Great Powers7 started noting the negative depictions of “Oriental” gender and sexuality proliferating in the Western (notably French, English, and German) imagination. Such depictions presented the gender world of the Oriental Other as unnatural, immoral, and unjust, thereby serving to reinforce imperialist ambitions abroad (we must rule them since they are not fit to rule themselves) and heteronormative ideals at home (we must demonstrate our superiority by not behaving like them).8

In response to this hostile othering process, so the going scholarly thesis, Western (read heteronormative) gender norms were adopted across a variety of Middle Eastern contexts. This, of course, happened as part of a more general trend towards “Westernization,” a trend ranging across all aspects of life from medicine to the military, literature to philosophy, architecture to fashion to the calculation of time itself. It is easy to explain this trend as a sort of defensive reflex, or as a desire to “catch up” with rival powers whose political, economic, and cultural trajectories were seen as a mounting threat. But we should beware of simply casting the issue in a defensive or competitive light. A genuine faith in the 19th-century ideology of progress, coupled with a genuine admiration for whoever or whatever seemed to represent said progress, was equally at play.

We should also keep in mind the bigger picture that, throughout history, Constantinople has been defined as much by its capacity for change as for constancy. The city’s remarkable geographic centripetality demands a receptivity to influences from literally all directions, influences that, once received, are transformed into something uniquely Constantinopolitan. This was well noted by Constantine the Great when he made the city the capital of Christian Rome in 330, and equally by Mehmed the Conqueror when he made it the capital of Muslim Rome in 1453.9

It is before this background that we can read the (in)famous proclamation by Ottoman statesman and reformer Ahmed Cevdet Paşa, who wrote in his Ma’rûzat, a 19th-century Ottoman history commissioned by Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876-1909):

Women-lovers multiplied while boy-beloveds decreased in number. The People of Lot were seemingly swallowed by the earth. The love and inclination towards young men, which had been a famous and habitual part of Istanbul life, was transferred to girls, as should be the case by nature.10

We can already discern the deep Western influence on Ahmed Cevdet’s thinking in the way he phrases the issue. First, there is the binary, either/or fashion in which he contrasts the “inclination towards young men” with that towards “girls.” Then, there is the concept of “nature,” which he invokes, in line with 19th-century Darwinian (and Victorian) thinking, to suggest that something (not explicitly named as, but implied to be) “unnatural” has been replaced with something “natural,” namely heterosexual desire as the only form of sexual desire justified by species propagation.

But Ahmed Cevdet also decorates the passage with a Quranic reference, mentioning the “People of Lot,” who, according to the Quran, “approach males […] and leave what your Lord has created for you as mates” and are punished for their transgression by God who makes “the highest part [of their city] its lowest” and rains “upon them stones of layered hard clay.”11 Both “swallowed by the earth” and “making the highest part its lowest” can be read as earthquake references, enabling Ahmed Cevdet to rhetorically square the circle of (Western) social progress and (Islamic) divine justice.

While 21st-century scholarship on gender in the Middle East does not necessarily confirm the apocalyptic abruptness of this change as pronounced by Ahmed Cevdet, it nonetheless reaffirms his basic contention of change in its broad strokes. Here is Khaled El-Rouayheb, writing in 2005 on the Arab-speaking world:

Between the middle of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth, the prevalent tolerance of the passionate love of boys was eroded, presumably owing—at least in part—to the adoption of European Victorian attitudes by the new, modern-educated and westernized elite.12

And here, writing in the same year on the Iranian context, is Afsaneh Najmabadi:

A sense of pleasure, which saw both handsome young men and beautiful young women as objects of desire, [was] reeducated and disciplined into heteronormativity by the end of the nineteenth century.13

As we can see, things have become somewhat more nuanced since Ahmed Cevdet. El-Rouayheb, while sticking to the geological metaphor, at least shifts it from earthquake to erosion, and Najmabadi points beyond the boy/girl-love binary by allowing for a “sense of pleasure” that could potentially encompass both. Still, all three passages suggest that the change was monolithic (culture changed as a whole), linear (culture changed in a single, specific direction), and complete (culture reached an end point where one gender world had been replaced by another). It is these three assumptions that I would like to erode here.

I will do so by demonstrating that the Tifli Stories published in the 19th century display a variety of gender norms, and that this variety has less to do with change over time than with coexisting, competing print technologies. A traditional, complex but coherent gender world, well-established prior to the 19th century, found expression via the print technology of lithography. At the same time, there was a revisionist engagement with this gender world, influenced by 19th-century Western ideas, via the print technology of typography. These two trends ran parallel to each other within the same genre, and even though typography appears to have outlasted lithography, it never “replaced” the latter with a new, coherent worldview, even one as broadly defined as “heteronormativity.”

Print Technologies

The printing press was known and used among Jewish and Christian communities in the Ottoman Empire from the late 15th century onwards.14 However, printing in Arabic letters or the Turkish language was banned until 1729, when unique permission was granted to Ibrahim Müteferrika, an Ottoman civil servant of Transsylvanian—and Unitarian—origin,15 to establish a typography press producing non-religious texts in Ottoman Turkish. Müteferrika only published 17 titles, and the Ottoman Turkish printing press remained a mere curiosity until about a century later.

The Ottoman “failure” to adopt the printing press in any significant way prior to the 19th century is an oft-cited example of the empire’s “backwardness” vis-à-vis Europe. There are a variety of reasons for this supposed failure. One involves a blend of economic and artistic considerations. Manuscript production had spawned an entire industry with its own supply chains spanning the breadth of the empire and beyond; its own guilds of craftsmen including scribes, illustrators, and binders; and its own forms of high artistic expression, most notably calligraphy and miniature painting. For a long time, this economic-artistic complex was able to stand its ground against the artlessly efficient printing press.16

Then, there was the matter of content. As evident from Müteferrika’s limited mandate, the printing of religious material was banned. This was partly because the production of religious texts—above all the Quran, which is, to Muslims, the literal word of God, but also legal texts, which are, as part of the sharia, religious texts themselves—demanded a degree of precision not afforded by the error-prone typesetting process.

Much more pressing, though, was the question of state control over the production and dissemination of politically sensitive material. The religious and political fragmentation wrought by the Reformation in Europe, and the role of the printing press in this process, was not lost on the Ottomans. Müteferrika himself, a staunch opponent of the Catholic Church whose home town of Kolozsvár featured the foremost Unitarian printing press of its day, was predictably positive about the impact of the printing press.17 But this sentiment was hardly shared by his Ottoman overlords, who had a record of closing non-Muslim presses on their soil if they seemed to be fomenting sectarian strife.18

There is a tendency to look back on the printing press, and other retrospectively and teleologically labeled “achievements” and “milestones” of history, as if they had also been viewed as such at the time. This obscures how extremely controversial—not to mention extremely destructive—these “achievements” often were when they first came about: if the printing press facilitated the Reformation, it also facilitated the Thirty Years’ War, which is thought to have eradicated at least a quarter of the population in German-speaking Europe alone.19 Viewed in this light, the “failure” of the Ottoman state to adopt the printing press could actually be read as a remarkable success, one that helped to preserve unity—and peace—in the empire until the 19th century.

By then, the Ottomans had come to regard printing as an inevitability, and technological innovation had made it possible to avoid at least some of its pitfalls. In 1789, a new print technology by the name of lithography had been invented in Bavaria with the purpose of reproducing engraved images. Lithography was never intended as a replacement for typography, but that is exactly how the Ottomans used it. The technology enabled a scale of production and dissemination simply not possible with manuscripts, each of which was literally copied out by hand. At the same time, though, lithography preserved certain artistic features of the manuscript, most importantly the calligraphy, and also the accuracy that came with calligraphy but was compromised in typography.

An elaborately produced lithography text (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

An elaborately produced lithography text (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

Finally, since lithography made it much easier to incorporate images, many lithography prints were illustrated, just as certain manuscripts contained miniature paintings. But while the high art of miniature painting was reserved for prestigious and expensive works that were only accessible to the elite, the less artful lithography prints brought picture books to the people. Overall, then, lithography enabled a sort of compromise between the artistic integrity of the manuscript and the popular reach of the printed book—with the caveat that the overwhelming majority of the population was illiterate and would, at best, have had such books read out to them. By using lithography in this way, the Ottomans succeeded in innovatively adapting cutting-edge technology to local circumstances and needs.

From the 1860s onwards, with the establishment of the first popular newspapers in Constantinople, typography started crowding out lithography. Newspapers’ frequency of appearance and in-built obsolescence rendered typography the only feasible means of production. Many printers opened or switched to typography presses to meet the demands of newspapers and periodicals, which, in turn, started publishing books, pamphlets, and other printed material as well.20 Eventually, even commissions more suited to lithography would have gone to typography presses since these were more common and therefore cheaper. Lithography books, then, were the LPs of their day and typography books the CDs, marginalizing the former not thanks to superior quality but simply thanks to affordability and convenience of production.

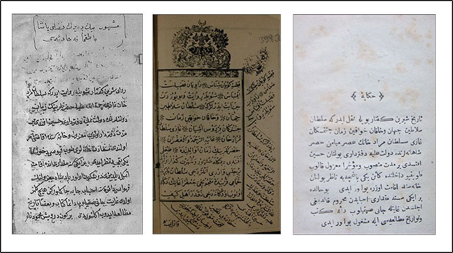

However, the difference between lithography and typography was one of content as much as form. Lithography didn’t just preserve certain formal characteristics of the manuscript; it also preserved the texts contained in specific manuscripts. Many lithography books are simply reproductions of pre-existing manuscripts, featuring the exact same text as the original, whether that original dates from the 19th century or earlier. In that sense, lithography books offer a continuation not only of the manuscript tradition, but also of the culture expressed through that tradition.

This was not the case with typography. The Ottoman newspapers ushering in the age of typography were founded by people like Ibrahim Şinasi, Namık Kemal, and Ahmed Midhat, entrepreneurs and popular writers who were also public intellectuals with a reformist bent. They cared not only about how they published, but also about what they published, hoping to reform Ottoman culture with their interpretations of Western ideas. Consequently, typography stood for a radically different kind of culture, a different kind of message, than lithography.

With both lithography and typography, then, we could indeed claim that the medium was the message. When a 19th-century Constantinopolitan Muslim strolled across the courtyard of a major mosque, where book vendors would set up their stalls on Fridays around prayer time, they would have known just by its printing technique, apparent from the cover, whether they were likely to be interested in a particular book or not, and what kind of discourse the book was likely to contain. They could have dismissed out of hand—and many probably did—either lithography or typography based on their political and cultural leanings.

In closing, it is worth stressing that the more traditional technology of typography was used for more innovative discourses while the more innovative technology of lithography served more traditional ones. And it is equally worth stressing that the technical victory of typography does not imply a discursive one. Typography carried the day because it was technically more convenient, not because it was discursively more convincing. If lithography had become largely obsolete by the end of the 19th century, this does not necessarily mean that the discourses it embodied had suffered the same fate.

The Tifli Stories

I have defined and described the Tifli Stories at length elsewhere;21 we could sum them up as an Ottoman version of the penny dreadfuls. Set in Constantinople during the reign of Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623-1640), they feature the sultan and his court entertainer, Tıfli Ahmed Çelebi (d. 1660), in supporting roles. The stories revolve around local settings; adventure plots with plenty of sex, intrigue, and violence; and everyday urban characters pursuing mundane goals such as wealth, status, and sexual gratification. They rarely take recourse to the supernatural and can be considered one of the first indigenous proto-realist prose genres in Ottoman fiction.

I will not claim to have “discovered” the Tifli Stories; scholars had mentioned specific stories before, and a handful had even talked about them as a group. But in 2013, I published the first book devoted to them,22 a book that defined them as a literary genre and included Turkish transliterations of all extant stories, some of them seen for the first time since the Ottoman Empire. I have continued to draw on the stories for my subsequent work on Ottoman culture, and as my views evolve in conversation with cohorts of students and colleagues across disciplines, I keep discovering new aspects to them and challenging my own previous readings of them.

Such is the beauty of Ottoman Studies: The field is so utterly neglected, and most of the research in it so utterly pedestrian, that with a bit of wit, work, and wherewithal, you can unearth entire genres that no one since the empire has talked about. A scholar of, say, English or French literature can only dream of getting “first look” at a text, leave alone a whole genre, that has not already been analyzed to death by wave after wave of modern scholarship. But sadly, this dearth of serious attention has also led to the field being infested with utter mediocrities who, rather than foray into the vast possibilities before them, have been content to cluster in cliques that produce uninspired, derivative work; keep the field locked up against inquisitive intruders; and divvy up its resources among themselves.23

The Tifli Stories have their origins in oral culture—which includes manuscripts, since these were largely produced for oral recitation rather than silent, individual reading.24 Whether read out loud from written texts or recreated on the spot, the genre was in circulation among the urban storytellers of Constantinople, notably the meddahs,25 presumably since the days of Tıfli Ahmed Çelebi himself. Still, there is no proof that our extant stories were originally told by Tıfli; rather than constituting a fixed body of texts, they are part of a folkloric and collective tradition whereby each retelling is a reinvention, free to diverge from previous retellings and adapt the story in whatever way it sees fit.

The 19th-century stories we will be looking at here are very much part of this dynamic and emergent tradition. Even though they were printed and sold as commercial products, they are not bound by modern considerations of authorial attribution or copyright. Most of their authors are anonymous, and some of the same stories were rewritten and reprinted in different versions using different print technologies over the course of the century. Overall, we have five different stories printed a total of eight times:

- Leta’ifname (“Book of Pleasantries,” lithography, 1851) and Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi (“The Strange Story of the Lady with the Dagger,” lithography, 1851-52) tell the story of a boy-beloved who squanders his inheritance, becomes the lover of an influential lady, and embarks on an affair with her odalisque.

- Hikaye-i Tayyarzade (“The Story of Tayyarzade,” typography, 1872-73) and Tayyarzade Hikayesi (same title, lithography, 1875) tell the story of a boy-beloved who enters the service of a former Ottoman courtier, becomes estranged from his master, but must rescue him when the latter gets abducted by a crime ring. In addition to the typography and lithography versions, we are fortunate enough to have a manuscript version of this story, entitled Meşhur Binbir Direk Fazli Paşa Batakhane Hadisesi (“The Famous Incident at the 1001-Columned Fazli Pasha Den of Vice,” undated).

- Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (“The Story of Cevri Chelebi,” typography, 1872-73) tells the story of the young rake Cevri Çelebi as he competes with Rukiye, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, for the affections of the boy-beloved Abdi.

- Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (“The Story of Tifli Efendi,” lithography, 1875) and Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi (“The Famous Story of Tifli Efendi and Bloody Bektash,” typography, 1882-83) tell the story of Tifli Efendi himself and how his prolonged feud with the notorious courtesan Bloody Bektaş eventually leads him to enter the service of Murad IV. The lithography version of this story is contained in the same book as the lithography Tayyarzade Hikayesi.

- İki Biraderler Hikayesi (“A Tale of Two Brothers,” typography, 1883-84) tells the story of a young girl who must escape the clutches of an ill-intentioned wealthy young man and, in the process, encounters two boatmen, one of whom threatens her while the other tries to protect her.

In addition to these five stories, I will draw on one more that only survives in manuscript form. The manuscript is undated and might well precede the 19th century, but I will include it since it helps us explore the continuities between manuscript and lithography stories as discussed earlier:

- Hikayet (“Story,” a generic title, also known as Sansar Mustafa Hikayesi or “The Story of Weasel Mustafa”) tells the story of Weasel Mustafa, a young rake who abducts the boy-beloved Ahmed and goes on the run when Murad IV, himself infatuated with the boy, mobilizes his forces to apprehend him.

The story of Tayyarzade in three versions: manuscript (undated), lithography (1875), and typography (1872-73)

The story of Tayyarzade in three versions: manuscript (undated), lithography (1875), and typography (1872-73)

As hinted at earlier, the lithography stories of the 19th century still feature the traditional gender world of Ottoman Constantinople as found in the manuscript stories as well; Tayyarzade, the only story of which we have both manuscript and lithography versions, is virtually identical from one to the other. There are no fundamental changes to this world whether a particular lithography story is published earlier or later in the century.

The typography stories showcase various attempts to move away from this gender world and experiment with new ideas. But even at their most radical, these experiments remain mere modifications or riffs on the existing template. If one looks beyond the obvious but superficial differences, the continuities outweigh the contrasts, and the new ideas are neither particularly well-adapted to the traditional—and structurally enduring—worldview, nor sufficiently well-developed to supplant it with a credible alternative.

Explicit Content

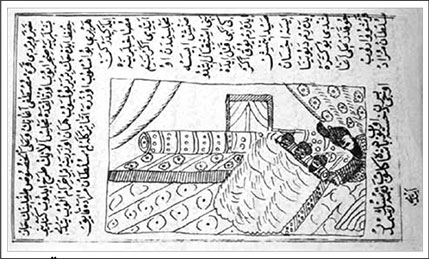

The manuscript-lithography tradition features sex as a normal, self-evident, multi-faceted aspect of both the stories and storytelling itself. The boy-beloved, who has sex with young rakes, older men, older women, slave girls, and prostitutes alike, is at the center of this sexual world. The ways in which sex enters the story are varied: it can be obtained by force, traded as a commodity, or based on mutal attraction. Equally varied are the effects for which the stories employ sex: it can be used for pornographic arousal, comic relief, or sensual/aesthetic stimulation. But in all cases and variations, sex is always present, and present in an uninhibited way. Here is an example from Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (lithography, 1875):

The youngster untied his belt, pulled a pillow under himself, and made like a bridge. Seeing the piece before him like a pink pussy, Kara Mustafa took his own thing in his hand, stroked it up and down, and shoved it in place. In the meantime, Tifli was enjoying himself in the garden, drinking coffee, smoking opium, and wondering whether the youngster had taken the whole thing. Inside, they finished one round of the love pipe. But this youngster was so fresh and clean, and Kara Mustafa could play both bottom and top, even if the former only happened once in a blue moon, when his nature felt inclined towards it. Since he enjoyed this youngster so much, he couldn’t control himself and said, “let me get my pleasure from this one like a girl, without lifting my ass, while Tifli is still outside.” And so, he pulled a pillow under his waist, lifted his legs, and finished his business.26

Tifli, Kara Mustafa, and the “youngster” sharing a bed when Murad IV walks in (Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi, 1875)

Tifli, Kara Mustafa, and the “youngster” sharing a bed when Murad IV walks in (Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi, 1875)

The typography stories are of a markedly more prudish persuasion: they feature virtually no sexual content at all. The contrast is clearest between lithography and typography versions of the same stories. Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi (1882-83), the typography version of Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (1875), not only omits the sex scene above, but eliminates the characters of Kara Mustafa and the “youngster” altogether, along with the entire subplot in which they are embroiled. Similarly, the sex scenes in Tayyarzade Hikayesi (1875), printed in the same lithography book as Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi, are absent from the typography Hikaye-i Tayyarzade (1872-73).

The difference is not correlated with publication date but with print technology: sexual content is absent from typography stories regardless of whether they were published before, or after, lithography versions of the same stories. In other words, sex scenes do not disappear over time. They are consistently present in lithography stories and consistently absent in typography ones.

There is one important exception to the general prudishness of the typography stories, and that is Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (1872-73). The sexual encounter, here, takes place between the merchant’s daughter Rukiye and the boy-beloved Abdi, and is recounted in three stages. The first of these finds the couple in a carriage as they are driven to Rukiye’s Bosphorus mansion:

Rukiye Banu slipped the cover off Abdi’s head, saying, “my lord Abdi, there is no patience left in me.” Like cream and honey mixed in one pot, they fell into each other’s arms. So intoxicated were they with the other’s smell, sweet like a budding rose, that they couldn’t even begin to kiss each other.

In the second stage, the couple proceeds to the mansion’s hamam:

“Rise, my lord,” Rukiye Banu said to Abdi, “let’s go to the hamam together.” She led Abdi to the changing room, undressed him with her own hands, wrapped him in a silk bath towel, disrobed and took a silk bath towel herself, and slipped on a pair of bejeweled sandals. Then, she took Abdi’s hand in hers and, kissing and squeezing each other, they entered the hamam. Crystal skin exposed and hidden birthmarks revealed, they joked and teased each other, enjoying a hamam session the likes of which cannot be described.

The third stage, finally, culminates in the sex itself:

Evening fell, beeswax candles lit up, and the odalisques left them alone in the bedroom. They undressed, got under the bedsheets with only their shirts left on, took these off as well, and clasped each other in a firm embrace. And the pleasure they had that night can neither be recounted by tongues nor recorded by pens.27

The differences between this crescendo of sensual pleasure and the mundane sex scene in Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi could not be more striking. The boy-beloved’s partner is not an older man but a young girl. The sexual engagement is not abrupt but gradual. The sentiment is not crude but tender. The context is not transactional but romantic. The act is not quasi-exposed but intensely private. The pleasure is not one-sided but mutual. The language is not explicit but implicit. And once again, let us mark that the difference is not correlated with publication date but with print technology: the typography Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (1872-73) was published before the lithography Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (1875).

The Boy-Beloved and His Older Male Pursuer

As should have become exceedingly clear by now, the boy-beloved is the pivotal figure of the manuscript and lithography stories. In all six of them, he is the main object of desire, and in four, he is complemented by an older male pursuer. I will not go into further detail about these figures here; my previous article28 on the topic can serve as a starting point for those who want to find out more.

The boy-beloved at an opium café (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

The boy-beloved at an opium café (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

When we turn to the typography stories, we find that only two out of four feature boy-beloveds, only one an older male pursuer, and none a sexual relationship between the two. Again, the contrast is clearest when we juxtapose lithography and typography versions of the same story. The lithography Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (1875) features two boy-beloveds (one named Cemal, and the nameless “youngster” from the above quote) and two older male pursuers (Tifli himself and Kara Mustafa), while the typography Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi (1882-83) omits both boy-beloveds as well as the figure of Kara Mustafa.

In Hikayet (undated manuscript), Tifli himself professes that “I have never chased after women in my life; I don’t even like my own mother.”29 In Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi (typography, 1882-83), this profession has turned into a mere unconfirmed rumor, with the (female) courtesan Bektaş teasing Tifli by saying, “I was under the impression that my lord’s nature inclined towards boy-beloveds and he had no fondness for women” and Tifli asserting his devotion to Bektaş in response.30

In the typography stories, then, there is a trend towards de-emphasizing the boy-beloved and his attendant network of desire. When I discuss this phenomenon with my students, I often come across a tendency to view this as a “good thing,” in the sense that some kind of perverted, pedophiliac tendency in the culture is being combated—and surely, this is how Ottoman reformers like Ahmed Cevdet wanted the matter to be understood. And I admit it is difficult to even approach the idea that somehow, we can distinguish the relationship between an older man (or woman) and a boy-beloved, as depicted in the Tifli Stories, from our contemporary notions of child abuse. But distinguish them we must, so let me outline why and how.

Most of us today grow up in cultures where experience is legally determined by age. For instance, alcoholic beverages, certain books and films, most forms of professional work, and the sexual realm as a whole, are only made legally accessible according to an abstract and numerically defined progression of age. In contrast, we might think about Ottoman culture (and, for that matter, “premodern” culture in general) as one in which age is defined by experience. Here, people age—that is, attain certain socially and legally recognized stages of maturity—not primarily through the passage of years, but through the experiences and achievements they accrue as a matter of course. The earlier—or later—these experiences and achievements take place, the earlier—or later—people age.

We witness this process of aging by experience in the Tifli Stories, for instance in the boy-beloveds of Leta’ifname (lithography, 1851) and Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi (lithography, 1851-52) who take legal control of their fathers’ households—and are engulfed in a world of drunken and sexual debauchery—as soon as their fathers die, without any regard to their numerical age. When Suleyman’s mother in the latter story tries to intervene in her son’s profligate lifestyle, he brushes her aside with the comment, “shut up, whore, the possessions are mine, the property is mine, I’ll play as I want and chase you barefoot out the door.”31 Similarly, these characters embark upon working life not when they reach a certain age, but as soon as they have squandered their inheritance and fallen into destitution.

It is through the same process that young people mature into objects of desire. In the Tifli Stories, older male or female pursuers of boy-beloveds are usually not just attracted by physical characteristics (even though these play an undeniably prominent role). They are also drawn to a certain level of mental and cultural achievement. The best example is Hüseyin Efendi, the former Ottoman courtier who pursues the boy-beloved Tayyarzade. In Tayyarzade Hikayesi (lithography, 1875), Huseyin expresses his yearning for companionship as follows:

There is no discerning, refined person with whom I could converse, who would fathom my conversation and be capable of response. I have not come into possession of such a person!

Huseyin’s confidant, a dervish by the name of Mahmud, has a suggestion:

My sultan, there lives a refined32 youngster in the quarter of Şehremini. He is called Tayyarzade Şemseddin Efendi. He is around eighteen or twenty years old, has a pleasant voice, is elegant and refined, speaks Persian well, also understands Arabic, sings beautifully, is well-versed in music, a beauty to behold, plays the santur well, is skilled in calligraphy and wood carving, and draws fine portraits as well as certain other pictures. He is a delicate, fresh boy-beloved who has a mother, a lackey, and an odalisque. This is the kind of accomplished person he is. Let me present him to my lord and, God willing, you will be pleased.33

Tayyarzade is the perfect example for how experience makes age rather than the other way round, not because he is so young, but precisely because he is not so young anymore. How could an eighteen-to-twenty-year-old who can boast so many accomplishments still be considered a boy, leave alone a boy-beloved, and not an adult, a man? This is because, in spite of his stunning résumé, Tayyarzade lacks the one central accomplishment without which no one in Ottoman culture is ever considered a full member of the adult world: he is unmarried and has no heirs, i.e., he has not established his own household.

In Constantinopolitan culture, the boy-beloved is neither a man nor a woman nor a child, but a gender unto himself. People enter into this gender at a certain—subjectively determined—age, meaning once they have attained a certain level of mental maturity and cultural accomplishment, and they exit it at a different age, meaning once they have attained a different set of cultural goals. To a Constantinopolitan lady or gentleman with a predilection for boy-beloveds, being with someone below the required level of accomplishment would have seemed as reprehensible as what we would call child abuse today, where the attraction appears to be based precisely on the physical and mental immaturity of the desired person.

On the other hand, marriage and the establishment of one’s own household—as the entry ticket to full adulthood—was a universal goal in Constantinopolitan life, much more strongly imposed and desired than any of our contemporary rites of passage, for instance the obtention of a higher education degree. People were expected—and wanted—to achieve this adult status as quickly as possible, and so, the boy-beloved was a gender they would have been keen to leave behind in due course. If a person was less than keen and overstayed their welcome, they risked being pathologized and censured by the community.34

We have to conclude, then, that the stigmatization of the boy-beloved, and of boy-love in general, by 19th-century reformists such as Ahmed Cevdet was not simply a matter of heteronormativity but, equally importantly, one of ageism. These thinkers were not just concerned with imposing a gender binary on a culture that went beyond it, but, at the same time, with imposing an ageist quantification of life whereby what a person could do, and who they could do it with, depended not on their subjective maturity, but on an arbitrary numerical age. From Ahmed Cevdet to our day, we have come a certain way in questioning the impositions of heteronormativity. It would be hard to say we have done the same for the impositions of ageism.

The Rake’s Progress

As we have seen, the typography stories evince a tendency to suppress the figures of the boy-beloved and his older male pursuer. In so doing, they free up the roles of the male protagonist and antagonist, roles they fill not with new male figures or ones imported from Western literatures, but by re-tooling a traditional male figure who is already part of the manuscript-lithography cast. This figure is the levend or, as I will call him here, the rake.

The rake is an unmarried young man, free from household supervision, who does not assume the role of boy-beloved but of a social and sexual predator. He is a volatile free agent who lives outside the norms of the community. In the manuscript and lithography stories, he sometimes appears as an outlaw hero, like Weasel Mustafa in Hikayet (undated manuscript) who, for all his illegal exploits such as abducting the boy-beloved Ahmed, escaping the justice of Murad IV, and killing numerous people in the process, becomes the stuff of urban legend. At one point, Mustafa boards a ferry in disguise and overhears the passengers singing his praises:

They say that he is a valiant champion, that there is no other hero as strong and dashing in all of Istanbul. May God not deprive us of such champions, and may each mother who has one bear another. It would have behooved Sultan Murad at the time to grant that hero full clemency and take him in his service, for such a hero cannot be taken alive, and killing him is deplorable.35

But the rake provokes awe and trepidation in equal measure. When the passengers realize that Mustafa is actually among them, “most of them flung themselves into the sea out of fear.”36 The rake, then, is equally likely to be a menace to the community, a role that is emphasized in Leta’ifname (lithography, 1851) and Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi (lithography, 1851-52), where a gang of rakes seduces the boy-beloved into wasting his inheritance on their pleasure. Here the scene from the latter story where the rakes ingratiate themselves with the boy-beloved Suleyman after his father Halil’s death by staging a fake display of grief:

The world is never in want of shameless ne’er-do-wells who roam around without occupation, ensnare profligate heirs, eat up all their possessions, and finally send them destitute into oblivion. […] When they heard of Halil Efendi’s death, the ones named Charity-Wrecker, Weasel Hasan, Sly-Son, Wily Veli, Crate of Mischief, and some other dissolute fellows surrounded the grave. After everyone had dispersed except the moaning and groaning boy, two or three among them wailed: “Oh my lord, Halil Efendi, you were our steady hand, our seeing eye, our benefactor, our master in this world! Until this day, we were graced with your bread and blessings!”37

The epithet of “Weasel” is not the only thing that Mustafa in Hikayet and Hasan in Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi have in common. Both characters have no money, income, or trade; both seduce boy-beloveds; both frequent taverns and prostitutes; and both employ questionable means such as cunning and violence to achieve their ends. Such is the ambiguity of the rake that essentially the same character can be portrayed as a paragon of heroism in one story and a harmful parasite in the next.

Suleyman and the rakes at a tavern (Hançerli Hanım, 1923-24)

Suleyman and the rakes at a tavern (Hançerli Hanım, 1923-24)

Turning to the typography stories, we see that two out of four feature rakes in leading roles. These are also the only typography stories that have no manuscript or lithography versions, and, as we will see, there is reason to assume they were originally conceived in and for the typography medium. The stories in question are Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (1872-73) and İki Biraderler Hikayesi (1883-84). Cevri, the eponymous rake of Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi, starts out in the exact same manner as the rakes in Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, namely by ingratiating himself with a boy-beloved, Abdi, who is grieving for his father Yusuf:

Cevri Çelebi said “this is my chance” and mingled with the crowd. He saw they had put Yusuf Çavuş’s corpse on the washing board. After washing him, they placed him in the coffin, and his son Abdi approached in tears. Seizing the moment, Cevri flung his arms around the coffin, started to wail, and exclaimed, “My lord, where are you going, leaving me here alone? How many times did you call for your servant Cevri when food was prepared? And where is he now, the one whose meals I shared? Noble and adored, now that you are gone, who shall give me food?”38

But unlike the rakes in the lithography Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, Cevri is not censured for his behavior. While Suleyman’s mother in the lithography story tries to dissuade her son from associating with the rakes, Abdi’s mother gives Cevri her blessing: “May you be as my own son in this world and the next, and may my son be as your brother and entrusted to you by God.”39 Just like Suleyman and his rakes, Abdi and Cevri embark upon a life of drunken debauchery, but in contrast to the lithography story, this lifestyle has no negative effect on Abdi’s finances or character.40

While Cevri is not a villain like the rakes of Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, neither is he a hero like Hikayet’s Weasel Mustafa. Much like Mustafa, who abducts the boy-beloved Ahmed and hides him from the sultan’s officers, Cevri helps the boy-beloved Abdi conduct an illicit affair and hides him from the sultan’s officers when the affair is discovered. But while both Mustafa and Cevri are eventually pardoned by the sultan, Mustafa is pardoned for his heroism, while Cevri is pardoned thanks to a lucky break: the sultan had previously drunk a cup of coffee at his house while patrolling the city in disguise.41

In conclusion, the rake’s behavior in the typography Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi closely resembles the behavior of rakes in manuscript and lithography stories. However, while the behavior itself is near identical, its connotations are not: Cevri’s duplicity and debauchery have no ruinous consequences, and his deeds are viewed as neither reprehensible nor commendable. The typography story, then, normalizes the figure of the rake,42 but does so without offering any modification to his behavior or any explanation for why this behavior should no longer be viewed as extreme. By a narrative sleight of hand, the rake is assimilated into the community without either the rake or the community having to undergo any change.

Let us turn now to the rake’s sexuality. Like the manuscript and typography rakes, Cevri is involved with a boy-beloved. But he has to compete for the boy-beloved, not with an older male pursuer—like Murad IV in the manuscript Hikayet—but with an adolescent girl. Cevri and Abdi’s life of debauchery comes to an abrupt end when Abdi falls in love with the merchant’s daughter Rukiye. At points, the relationship between Cevri, Abdi, and Rukiye almost comes to resemble a love triangle:

After some jokes and pleasantries, Rukiye Banu said, “Cevri Çelebi, do you love Abdi very much?” Cevri gave no answer. But Rukiye insisted: “Out with it, my dear, do you love Abdi very much?” Cevri finally answered, “My lady, I love Abdi to a fault. In Istanbul, they’re kind enough to credit me with discernment, and I’ve never seen such a beauty among men as Abdi, or as yourself among women. But since I’m in love with Abdi, I wouldn’t exchange a hair of his for ten girls as comely as you.” Abdi resented the remark, but Rukiye didn’t mind—in fact, she enjoyed it. “Bravo, Cevri Çelebi,” she approved, “If you’re in love, that’s how it should be.”43

While Cevri stays true to his love for Abdi, the story makes him at least contemplate the possibility of an “exchange” between Abdi and Rukiye. This possibility becomes reality in our final typography story, İki Biraderler Hikayesi (1883-84), where the boy-beloved as the central object of desire has disappeared, only to be replaced by a nameless young girl. No less than three rakes compete over this girl: Kazazzade, a young heir with nefarious intentions who lures her to his Bosphorus mansion; Hasan, a rake who has squandered his inheritance and is working as a boatman when he helps the girl escape Kazazzade’s clutches; and Huseyin, Hasan’s boon companion, who takes the girl for a prostitute and attempts to sexually assault her.

These three characters depart from our previous rakes in numerous ways. Most obvious—and innovative—is that they are no longer interested in boy-beloveds but girls. But they are also different from previous rakes in somewhat less innovative ways. Kazazzade borrows his wealth and Bosphorus mansion from the older male and female pursuers of the manuscript and lithography stories, while Hasan and Huseyin borrow their backstory of squandered inheritance from the boy-beloveds. In effect, the story uses rakes to fill the narrative roles formerly occupied by older pursuers and boy-beloveds by taking the latter’s attributes and redistributing them among the former.

It is not surprising that the rake should take center stage in the typography stories: He is a young, sexually aggressive man who, by that virtue, can play the male romantic lead in a reformist-minded story about a same-aged, heterosexual couple. The authorial intent is clear: to normalize, socialize, and diversify the rake into a range of as-yet unmarried young men looking for—or at least acknowledging the possibility of—female romantic partners.

But the effort to socialize the rake lacks any real conviction: he remains a transgressor, and it is unclear how and why the community at large has come to accept him. And the effort to diversify him only results in a Frankensteinian menage of characters mixing rakes, boy-beloveds, and older pursuers, characters who only exist in Constantinopolitan culture as a figment of their author’s imagination.

Finally, the reorienting of the rake’s desire44 from boy-beloveds to young girls, while in line with Ahmed Cevdet’s pronouncement, creates more problems than it solves. Far from being a handicap, the manuscript and lithography rake’s penchant for boy-beloveds is actually his saving grace. For no matter how transgressive he might appear, he never breaks the ultimate taboo of Constantinopolitan sexuality: he does not come after anyone’s daughter or wife.

Not so the typography rake. His relations are not (just) with boy-beloveds for whom such encounters are par for the course, but with young girls for whom any illicit male contact before marriage could spell social ruin, and for whom the rake, with his anti-social lifestyle, is anything but a suitable marriage prospect. The same-aged, heterosexual story option opened up by the rake as male lead, then, is actually no option at all.

Ladies, Odalisques, Prostitutes

The main female figures that populate the landscape of desire in the manuscript and lithography stories are the lady, the odalisque, and the prostitute. In four out of six stories, the boy-beloved is pursued by older, influential ladies while he himself pursues odalisques. In two of these stories, Meşhur Binbir Direk Fazli Paşa Batakhane Hadisesi (undated manuscript) and Tayyarzade Hikayesi (lithography, 1875), the lady and her odalisque also have connotations of prostitution, since the lady (Gevherli) has turned her mansion into a brothel. Finally, in the two remaining stories, the boy-beloved is not pursued by ladies, and himself pursues prostitutes. For a fuller exploration of all these figures, let me once again refer you to my previous article.45

Tayyarzade and Gevherli amusing themselves at Gevherli’s mansion-turned-brothel (Tayyarzade ve Binbir Direk Batakhanesi, 1924-25)

Tayyarzade and Gevherli amusing themselves at Gevherli’s mansion-turned-brothel (Tayyarzade ve Binbir Direk Batakhanesi, 1924-25)

Just like the boy-beloved and the older male pursuer, these female figures have a tendency to vanish from the typography stories. As above, we can find examples of this trend when we compare lithography and typography versions of the same stories. In the lithography Tıfli Efendi Hikayesi (1875), the courtesan Bloody Bektaş serves as an object of desire for Tifli and the nameless “youngster,” and simply fades out of the story towards the end. In contrast, the typography Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi (1882-83) does not employ Bektaş as an object of desire and has the character executed in the end.

Another example is Subha,46 the odalisque of the lady / brothel operator Gevherli, who catches the eye of Tayyarzade when he infiltrates the brothel to save his master Huseyin. After the brothel is raided and Gevherli killed at the end of the lithography Tayyarzade Hikayesi (1875), the odalisque is simply transferred into the possession of Tayyarzade. In contrast, in the typography Hikaye-i Tayyarzade (1872-73), she ends up married to Tayyarzade. Again, the earlier date of the typography story reminds us that we are not dealing with a change over time in attitudes towards slavery, but rather with competing discourses embodied by competing print technologies.

Out of our four typography stories, Hikaye-i Tayyarzade is the only one featuring the lady and the odalisque, while Meşhur Tıfli Efendi ile Kanlı Bektaş’ın Hikayesi is the only one featuring a prostitute in a major role. In the other two typography stories, these figures do not appear at all and are replaced by free, adolescent girls.

We can trace the absence of odalisques and prostitutes to the influence of 19th-century Ottoman reformers, who regarded prostitution and household slavery as social evils rather than simple facts of life. The absence of the older lady can be related to the same reformers’ ageist approach to gender as discussed above. In the manuscript and lithography stories, older male and female pursuers of boy-beloveds behave in roughly the same way; their gender role is determined more by their age and social status than by their biological sex. The fact that typography stories tend to exclude both of these figures, rather than just the older male pursuer, supports the claim that ageism was just as determining to the reformist gender discourse as heteronormativity.

The Girl-At-Large

Just as the typography stories use the rake to fill the void left by the boy-beloved and the older male pursuer, they replace the lady, odalisque, and prostitute with a new female figure: the free, adolescent girl or, as I will call her here, the girl-at-large. She is the female protagonist of the two typography stories that have no manuscript or lithography versions, namely Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (1872-73) and İki Biraderler Hikayesi (1883-84). We never encounter this figure in the manuscript-lithography tradition, which strengthens my suspicion that these two stories were originally conceived in and for the typography medium.

The girl-at-large of Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi (typography, 1872-73) is the merchant’s daughter Rukiye, who orchestrates an affair with the boy-beloved Abdi by contacting him via go-betweens, taking him to her Bosphorus mansion in her carriage, and initiating a sexual relationship with him there. This is an astonishing degree of agency for a 19th-century Constantinopolitan girl, even in fiction. It would appear, then, that Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi succeeds not only in introducing the figure of the girl-at-large into the Tifli Stories, but also in equipping this figure with an emancipatory potential that is nothing short of revolutionary.

This appearance, however, is deceiving. In fact, Rukiye’s behavioral pattern is a near-exact replica of that displayed by the Lady Hurmuz in Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi (lithography, 1851-52). In that story, it is the older lady who espies the boy-beloved Suleyman from her carriage, uses go-betweens to summon him to her Bosphorus mansion, and begins a sexual relationship with him there. Rukiye, then, is best understood as an older female pursuer rewritten as a girl-at-large, just like Kazazzade in İki Biraderler Hikayesi, with his wealth and Bosphorus mansion, is actually an older male pursuer in a rake’s body.

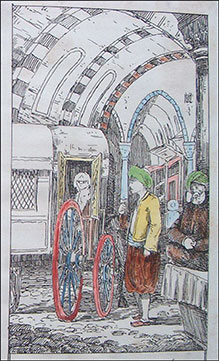

Hurmuz espies Suleyman from her carriage (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

Hurmuz espies Suleyman from her carriage (Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi, 1851-52)

Still, age is not the only difference between Rukiye and the older female pursuers of the manuscript-lithography tradition. These routinely get punished for their transgressions at the end of their stories: Raiye in Leta’ifname and Gevherli in Tayyarzade Hikayesi and Meşhur Binbir Direk Fazli Paşa Batakhane Hadisesi are executed; Hurmuz in Hançerli Hikaye-i Garibesi survives, but loses her estate to the boy-beloved Suleyman. There is not a single manuscript or lithography story in which an older female pursuer is rewarded for, or even just gets away with, her exploits.

Similarly, Rukiye’s behavior is repeatedly criticized by various characters throughout Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi. As she amuses herself with Abdi at her Bosphorus mansion, Cevri warns her that patrolmen might notice the indecent behavior. Soon thereafter, the mansion is raided, and Rukiye and Abdi go into hiding. Rukiye’s father is informed and discusses the scandal with the vezir, who asks him why he didn’t punish the girl. The father replies that had he known what was going on, he would have flayed his daughter alive, and promises to make an example of her as soon as she is caught.47

However, in stark contrast to the older female pursuers of the manuscript-lithography tradition, Rukiye is not punished in the end. When she and Abdi are finally found and brought before the sultan, he takes a liking to the couple and decides to wed them. Thus, the sultan acts as a deus ex machina to give Rukiye a happy ending where such an ending is denied to the older female pursuers. But this de facto legitimization by the sultan does not change the fact that common morality and law, as embodied by Rukiye’s critics throughout the story, regard her liaison with Abdi as illegitimate. By a narrative sleight of hand, Rukiye is reassimilated into the community without either her or the community having to undergo any change.

The final typography story, İki Biraderler Hikayesi (1883-84), takes a different approach to the girl-at-large. The nameless girl enters the story in the second act, where she falls into the rowboat of the rake Hasan while flinging herself into the Bosphorus to escape the clutches of another rake, Kazazzade. She tells Hasan her backstory in the first person: the daughter of an elderly manuscript illuminator, she helps her enfeebled father with his work as the family barely makes ends meet. One day, she is taken to Kazazzade’s mansion by her aunt, ostensibly to meet a suitable marriage prospect. In reality, though, Kazazzade has paid off the aunt to bring him the girl for his sexual pleasure. When the girl arrives at the mansion, only to find a party going on with numerous prostitutes in attendance, she grabs Kazazzade’s dagger, knocks over the table with the candles, escapes the mansion in the ensuing darkness, and jumps into the Bosphorus.

Hasan takes the girl to his own humble dwelling, which he shares with his boon companion Huseyin. The latter, however, is convinced the girl is a prostitute and even claims she has danced for him on occasion. When he starts to harass the girl, Hasan sees red, pulls his sword, and kills him on the spot. He throws the corpse in the Bosphorus, takes the girl to her father’s house, and, fatigued, falls asleep in his rowboat. In the morning, Tifli and the sultan board his boat in disguise, and he tells them the whole story. The sultan takes Hasan to the palace, has the girl and her father summoned, and finally weds the girl to Hasan, gifting them a sumptuous mansion and the girl’s dowry.

If Rukiye in Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi is essentially an older female pursuer in a young girl’s body, the nameless girl in İki Biraderler Hikayesi takes on many aspects of the role traditionally played by the boy-beloved. Like the boy-beloved, she comes from a respectable, if impoverished, background, allowing her a share of culture and education. Like the boy-beloved, the financial straits of her family influence her own life choices, and she feels the need to chip in. And like the boy-beloved, she encounters her pursuers not as an active, desiring subject, but as a passive object of desire.

However, while the boy-beloved at least has desires of his own vis-à-vis odalisques and prostitutes, the nameless girl evinces no desire for anyone at all. She is entirely desireless in her encounters with the three rakes, and gains agency only in refusing desire, in heroically defending herself against Kazazzade’s violent, physical manifestation of desire. It is in the act of escaping Kazazzade’s desire that she encounters Hasan, to whom she will end up married, but who, for his part, expresses no desire for her either. Again, Hasan’s main agency consists in refusing desire when he kills the third rake, Huseyin, for having violently manifested his desire for the girl.

So, in the end, when the sultan weds the nameless girl to Hasan, he weds two people who have met by coincidence, never expressed any desire for each other, and are, in fact, only united by their fight against desire. This union is the exact opposite of that between Rukiye and Abdi, who have come together by force of will, passionately desire each other, and break every norm and law in pursuing and consummating that desire. While the latter union celebrates volition and desire, the former celebrates the absence of volition and the struggle against desire.

Published in 1883-84, İki Biraderler Hikayesi is the last typography story of the 19th century. It is also the closest the Tifli Stories get to orchestrating a model heteronormative, ageist gender performance. The story eliminates same-sex and intergenerational desire altogether, limiting potential pairings to male and female protagonists of young, comparable age. The leading couple is forged through a series of (unrealistic) coincidences rather than their own volition, eliminating the problem of desire so vexing to prudish, reformist sentiments. Finally, by modeling the girl-at-large on the boy-beloved rather than the older female pursuer, the story creates a dominant male and submissive female pairing more in line with the Western ideal than that between Rukiye, the female, dominant, desiring subject, and Abdi, the male, submissive object of desire in Hikaye-i Cevri Çelebi.

In closing, it is worth our while to return to the curious fact that the girl-at-large in İki Biraderler Hikayesi gets to tell her own story in the first person, a unique occurrence in the Tifli Stories where we are otherwise guided through the events by an omniscient narrator. While this first-person perspective may seem empowering on one level, it also creates a deep ambiguity, for it leaves us without “outside” corroboration of the girl’s story about Kazazzade. This ambiguity is reinforced at the end of the story, where Huseyin’s adamant—and unrefuted—insistence that she has danced for him on occasion increases the suspicion that there might be something not entirely proper about the girl.

The story does not pursue this possibility, but even its mere existence shows how dangerous it is for a Constantinopolitan girl to expose herself in an unsupervised way to any male desire at all. Such encounters always leave a residual suspicion of impropriety hanging over the girl, even if the suspicion is left unspoken and even if the girl, as in İki Biraderler Hikayesi, behaves in a completely desireless way. Ultimately, then, even this story’s elaborate construction of coincidental and involuntary encounters is not enough to make the girl-at-large available to desire while also placing her on a safe moral footing.48 The morality of the girl-at-large remains an unresolved, and possibly unresolvable, dilemma.

Conclusion

The manuscript and lithography stories are consummate explorations of a well-established, centuries-old gender world in which male and female members of various age and status groups engage each other in complex networks of desire. While this world has its own rules and is definitely not a gender-fluid free-for-all, it equally definitely goes beyond the heteronormative and ageist ideas with which the typography stories try to reconfigure and streamline it into one based on exclusive relationships between young members of opposite sexes. The descriptive richness of the manuscript-lithography tradition is also mirrored in story length, which varies between 6,000 and 23,000 words, while the prescriptive sterility of the typography stories merely produces a length between 1,600 and 5,600 words.49

Rather than serving as a reflection of changing social realities, the typography stories are attempts to promote types, behaviors, and relationships that, in their presented form, do not exist in Constantinople and are more wishful than realistic. But it would be absurd to claim that the 19th century witnessed no social change at all, and this, coupled with the fact that lithography stories can be verbatim reproductions of older manuscript versions, leads me to conclude that lithography stories are not mere “explorations” of existing norms but also embalmings, enshrinings of a gender world that is being increasingly questioned and challenged. In its own way, this embalming is as much of a political gesture as the reformist inventiveness of the typography stories.

It has emerged from the preceding discussion that, at least in the Tifli Stories, the 19th century witnessed no monolithic, unidirectional change from one gender world towards an equally clearly defined other. Rather, two approaches to gender, one traditional and the other reformist, existed side by side, expressed in the same genre but separated by different print techologies. While the innovative technology of lithography was used as a tool of resistance to change, the traditional technology of typography was used as a medium of reform. And, as I emphasized earlier, the fact that typography won the day because of its technical advantages does not mean that the gender world of the lithography stories simply disappeared along with this medium.

Far from it; when we look at the manuscript-lithography stories, we encounter a fully realized, intricately detailed, and eminently plausible gender world that has come into being over centuries of cultural negotiation. The typography stories never succeed in replacing this world with an equally realized other; in fact, they do not even attempt it. Their authors are well aware that they cannot, say, take a Western novel, simply change the names, and relocate the setting to Constantinople; the result would read like parody at best and mere gibberish at worst. No, even the most reform-minded author needs to draw on the cultural toolkit offered by their own context if they wish to avoid obscurity and incomprehension.

As a result, even the most radical typography stories are essentially set in the lithography world. They offer not an adoption, but at best an adaptation of Western ideas about gender to local realities, an adaptation that is as piecemeal, tentative, and simplistic as it is creative and innovative. Intergenerational and same-sex desire are subjected to an attempt at banishment that never fully succeeds because, even where certain figures like the boy-beloved and his older pursuers are absent, their backstories and circumstances, their patterns of behavior and interaction, are simply assumed, more or less unchanged, by other figures such as the girl-at-large and the rake. What is absent in letter thus remains very much present in spirit.

Further, the traditional Constantinopolitan gender world, to the extent that it is altered, is never substituted by anything that makes sense from a social, cultural, or sexual point of view. Public space, effortlessly navigable by the boy-beloved or even traditional female figures like the prostitute, remains imagined as a highly dangerous space for the girl-at-large. Still, she must now somehow be made available, in this space, to male desire, which remains as volatile and unpredictable as ever. The young girl is “modernized” without making her any less beholden to traditional moral standards; the young man is “modernized” without making him any less predatory. How these two are even supposed to meet, leave alone form meaningful unions, remains unclear.

Ahmed Cevdet would have us believe that “the love and inclination towards young men” can simply be “transferred to girls, as should be the case by nature.” But as much as they occur in “nature,” young men and girls are themselves constructions of culture. They are not timeless, unchanging categories, and reorienting their desire means nothing less than redefining what they are. And, as the typography stories demonstrate, giving people someone new to be is a much taller order than giving them something (or someone) new to do.

1. Officially named Istanbul in 1930, seven years after the abolition of the Ottoman Empire, until which point a variety of names were in circulation, with Constantinople, or the Arabized قسطنطينيه (Kostantiniyye), among the most common both in and beyond the empire itself. The name “Istanbul” is generally assumed to have derived from the Greek phrase εἰς τὴν πόλη (eis tin póli), which simply means in, or to, the city.↑

2. David Selim Sayers, “Sociosexual Roles in Ottoman Pulp Fiction,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 49.2 (May 2017), 215-232 [4 July 2022].↑

3. David Selim Sayers, “Sociosexual Norms and Print Technologies in Nineteenth-Century Istanbul,” 33. Deutscher Orientalistentag, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena, 21 September 2017 (see conference program, 141 [4 July 2022]); “Gender unter Druck: Normen und Technologien im Istanbul des 19. Jahrhunderts,” Osmanische Schnittstellen/Ottoman Crossings lecture series, Institute for Oriental Studies, University of Vienna, 8 November 2017 (see series program [4 July 2022]); and “Gender Norms and Print Technologies in Nineteenth-Century Istanbul,” Conference in Honor of Leslie P. Peirce, New York University, 4 May 2018, 17:47 onwards [4 July 2022].↑

4. The term “sex worker,” I believe, would be inappropriate in a non-capitalist context.↑

5. Female household slaves, from the Turkish odalık, which can be roughly translated as “chambermaid.”↑

6. For an extensive treatment of the boy-beloved in Constantinople, see Walter G. Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli, The Age of Beloveds, Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.↑

7. I am thinking here of the powers constituting, or following from, the Congress of Vienna (1814-15), namely the British, French, German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires.↑

8. For a detailed analysis of specific sources, see Dror Ze’evi, “The View from Without: Sexuality in Travel Accounts,” in Ze’evi, Producing Desire: Changing Sexual Discourse in the Ottoman Middle East, 1500–1900, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2006, 149-165.↑

9. The so-called “Byzantine Empire” was actually never anything else than the Roman Empire, and Mehmed the Conqueror had himself proclaimed Kaysar-i Rum (Caesar of Rome) after taking Constantinople.↑

10. Ahmed Cevdet Paşa, Ma’rûzât, ed. Yusuf Halaçoğlu, Istanbul: Çağrı Yayınları, 1980, 9, translation mine.↑

11. Quran, 26:165-166 and 11:82 respectively, translations from quranverses.net.↑

12. Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005, 156.↑

13. Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, 53-54.↑

14. N. Serpil Altuntek, “llk Türk Matbaasının Kuruluşu ve İbrahim Müteferrika,” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 10.1 (July 1993), 191-204, here 192. Altuntek specifies that the first Jewish printing press was established in 1493-95, the first Armenian one in 1567, and the first Greek one in 1627.↑

15. Niyazi Berkes, Türkiye’de Çağdaşlaşma, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2002, 51.↑

16. Gül Derman, Resimli Taş Baskısı Halk Hikâyeleri, Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayınları, 1989, 1-2.↑

17. Berkes, Türkiye’de Çağdaşlaşma, 56.↑

18. Altuntek, “İlk Türk Matbaasının,” 192.↑

19. Encyclopædia Britannica, “The emergence of modern Europe, 1500–1648” [11 July 2022].↑

20. Nuri Akbayar, “Osmanlı Yayıncılığı,” Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyet’e Türkiye Ansiklopedisi, ed. Fahri Aral, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1985, 1683.↑

21. Sayers, “Sociosexual Roles”; see also Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, Istanbul: Bilgi University Press, 2013.↑

22. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri. Incidentally, this article offers a major revision of some claims I made in that book. ↑

23. For a case study of such a clique, see Sayers, “The Real Academy in Exile (Censored),” The Faculty Lounge, 19 November 2021 [13 July 2022].↑

24. For a helpful discussion of oral culture and the place of manuscripts within it, see Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy, New York: Routledge, 2002.↑

25. For an extensive discussion of the meddah tradition of Ottoman urban storytelling, see Özdemir Nutku, Meddahlık ve Meddah Hikâyeleri, Ankara: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Başkanlığı Yayınları, 1997.↑

26. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 186, translation mine.↑

27. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 58, translation mine.↑

28. Sayers, “Sociosexual Roles.”↑

29. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 48, translation mine.↑

30. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 49, translation mine.↑

31. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 314, translation mine.↑

32. It is telling here that the original uses the female form of the adjective, zarife.↑

33. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 208, translation mine.↑

34. More on this in Sayers, “Sociosexual Roles.”↑

35. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 161, translation mine.↑

36. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 162, translation mine.↑

37. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 307-308, translation mine.↑

38. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 405, translation mine.↑

39. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 405, translation mine.↑

40. I originally made this point in Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 71-72.↑

41. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 413.↑

42. The story also normalizes the rake by giving Cevri a mother—no other rake in a Tifli Story has one.↑

43. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 410, translation mine.↑

44. I borrow the phrase from Joseph Massad’s influential essay, “Re-Orienting Desire: The Gay International and the Arab World,” in Massad, Desiring Arabs, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, 160-190.↑

45. Sayers, “Sociosexual Roles.”↑

46. Renamed “Sahba” in the typography version.↑

47. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 72.↑

48. Might her moral precarity also explain why this particular girl is the sole female protagonist of any Tifli Story to remain unnamed?↑

49. Sayers, Tıflî Hikâyeleri, 14.↑

Responses