How to Déplier Baroque

How to Déplier Baroque

Interview with Marina Nordera

by Tatiana Senkevitch (Paris, France)

WHETHER one thinks of the Baroque as a specific historical period or as an attribute of artistic life that endures to this day, there is a little doubt that Baroque-inspired art remains spectacular and primed for attraction and display.

The exhibition Déplier Baroque at the Centre national de la danse (CN D) in Paris, along with its accompanying program of performances, conferences, and round tables, explores the radiating effect of the historical Baroque on the art of dance and the arts in general. Rather than offering a chronological take on the history of dance in the Baroque, the exhibition plays on the Baroque’s imaginary and its animating, corporeal energy that continues to inspire artists in many fields to this day. The Baroque’s historical actors are highlighted: court and theatre dancers and ballet masters who authored remarkable treatises in which dance was considered as a noble and worthy artistic undertaking. Some of these authors complemented their considerations with graphic notations, sophisticated systems for visually recording steps and positions of dancers’ bodies in space. Rather like poetry or plays, Baroque dances circulated widely in print and became available for practice by contemporaries. This historical aspect of the exhibition, however, is placed in continuous dialogue with contemporary artists, sculptors, choreographers, dancers, and historians of culture, all inspired by the élan of the Baroque.

Which ideas animated the the exhibition? What kind of research is conducted today on Baroque culture and historical forms of dance? And which disciplines and methodologies are involved in such research? I had the opportunity to discuss these questions and more with the exhibition’s curator Marina Nordera, historian of dance and professor at the Centre Transdisciplinaire d’Épistémologie de la Littérature et des Arts Vivants, Université Côte d’Azur.

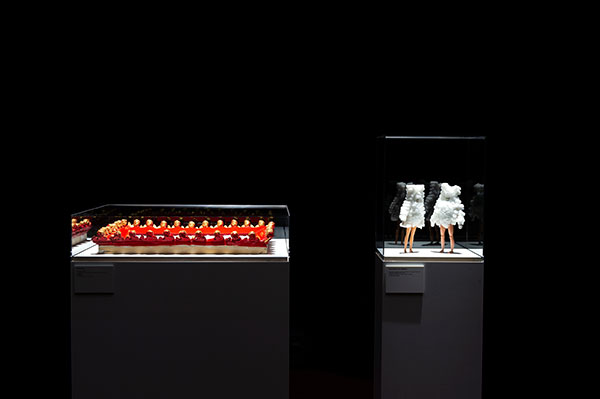

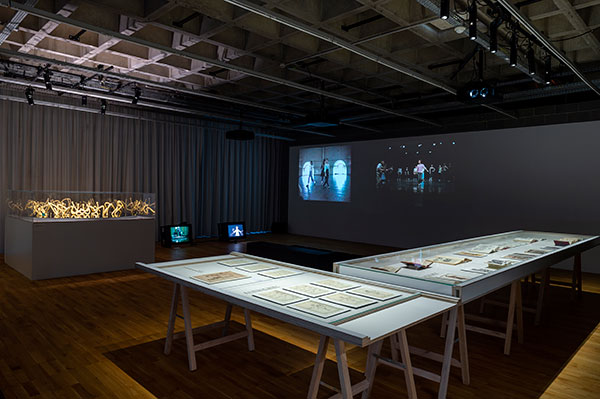

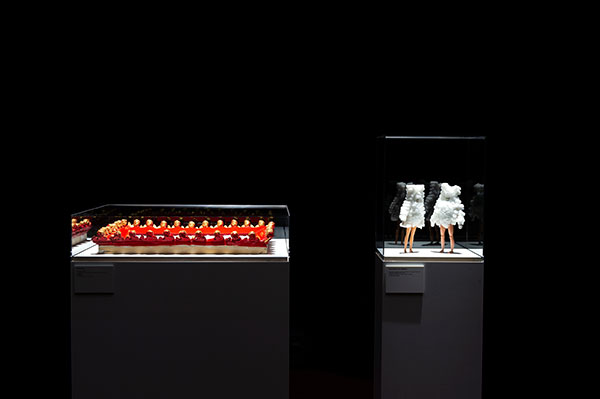

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

Tatiana Senkevitch: Marina, before you became a prominent scholar in the field of dance, you were a dancer yourself, performing with the companies Ris et Danceries of Francine Lancelot and Fêtes Galantes of Béatrice Massin. Could you please describe the genesis of this exhibition and its significance for your long-term engagement with Baroque dance?

Marina Nordera: About a year ago, the direction of the CN D asked me to submit a project for an exhibition on the Baroque. I felt honored and happy to receive the offer. But at the same time, I was deeply aware how much work lay ahead of me if I wanted to do justice to this enormous subject, especially since the CN D gave me carte blanche on the theme. I did not commit immediately as it took some time to think it through. Finally, I accepted the offer—it was hard to say no to such an enticing proposal, not least because the project allowed me to reflect anew on the two strings of my life: as a performer of so-called historical dance and, currently, as a university professor in an institutional milieu quite different from stage life. Curating this exhibition gave me an opportunity to interlace these two strings. I relied on all my experience, knowledge, and years of research to put this project in action.

I first joined a historical dance company when I was just twenty years old. At this age, one mostly acts rather than contemplating. After fifteen years as a professional dancer, I expanded on my dancing experience via my studies and research, my dissertation, and my enriching contacts with colleagues. Dancing itself became a bit distant for me through these years, perhaps too distant. And so, Déplier Baroque presented an opportunity to bring my current position and my artistic experience together. I conceived the exhibition as a sort of amusement, a play, while seeking a balance between the light whimsy of Baroque aesthetics and the knowledge required to expose the different modalities of a subject as vast and elusive as the Baroque.

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

TS: Déplier Baroque is a multimedia exhibition that spreads over two floors at the Centre national de la danse, a leading teaching and research institution devoted to the heritage of dance in France. Can you describe your criteria for selecting the wide-ranging pieces on display? What difficulties did the variety of media cause for you as curator?

MN: The CN D’s rich collections, including private archives, original documents, and audiovisual materials, were the starting point of the exhibition. Since its creation in 1998 on the initiative of the Ministry of Culture and Communication, the Médiathèque of the CN D has become one of the main collectors and producers of audiovisual documents on dance, particularly after acquiring the collection of the Cinemathéque de la danse.

Part of the sources, then, came from the CN D collection. For other parts, we relied on a partnership with the Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP) which helped us to identify artists whose work touches on the historical Baroque or baroque aesthetics one way or another. The Centre lent us an imposing sculpture, “Robe sans corps: sculpture de plis” by ORLAN, that we placed in the atrium. The sculpture renders folds in movement, symbolizing the Baroque’s dynamism.

Through the CNAP, we made contact with contemporary artists whose works bear on Baroque themes, such as the Australian artist Madison Bycroft. The French sculptor Jean-Michel Othoniel—well-known for his gilded glass sculptures adorning the fountains in the gardens of Versailles and for Les Belles Danses, the installation commissioned by the Versailles palace and inspired by the work of choreographer Raoul-Auger Feuillet, dance master at the court of King Louis XIV—lent us his sculptures and works on paper directly.

In the seven parts of the exhibition, we fuse historical documents, objects, and videos with works of modern and contemporary artists, creating a layered discourse on the Baroque.

We also obtained audio-visual documents that were not part of the CN D collections and produced some new ones. I conducted eight interviews with choreographers, researchers, and artists that form part of the exhibition but can also be accessed on the CN D website.

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

TS: Were there objects or documents that you would have liked to include in the exhibition but could not obtain for some reason?

MN: The original editions of treatises from the national heritage libraries were not accessible to us because the CN D is not, strictly speaking, a museum site but an educational facility and thus does not have a proper security system or display vitrines with controlled temperature and light. For example, I would have liked to show a violon pochette, a necessary accessory for ballet masters of the period, but here again, we could not borrow one for the same reasons.

We realized our limitations early in the process and tried to compensate for these lacunae with other solutions. As an example, I can refer to the model of Marie-Madeleine Guimard’s private theatre built in her hôtel particulier in Paris. Guimard (1743-1816) was a leading dancer of the Academie Royal de musique et de danse who was greatly admired by her contemporaries. We could not borrow a model of Guimard’s theater from the CNAP, but the artist Ezequiel Garcia Romeu created one, inspired by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s projects, on my demand.

TS: How did you come up with the fortuitous title of Déplier Baroque, which evokes so many key categories for the world of dance but also for the theory of the Baroque, specifically Le Pli. Leibniz et Le Baroque, the seminal book by Gilles Deleuze?

MN: I wished to have the word “baroque” in the title, as well as the idea of movement associated with this style. As we know, titles should not be too long. I had a brainstorming session with myself and thought about Deleuze, whose book has accompanied me since I started working on the Baroque, and decided to use the verb “déplier” as an infinitive that opens up the multiplicity of meanings, links, actions, and alliterations beyond the title of Deleuze’s book.

So, the title was born, also providing an assonance with the motion of plié, one that stands at the origin of all other steps in dance. Pliés are fundamental elements of dance but also essential to movement and dynamism in the world in general. I circulated the title among my friends, and they seemed to like it. Finally, the CN D accepted it and decided to use it not only for the exhibition but also for all other events surrounding it.

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

TS: One of the exhibition’s goals is to highlight an ongoing transmission of ideas from the historical Baroque to its contemporary manifestations. Could you explain how this transmission works in relation to the “technique of the body” in the Baroque period and its reinterpretation by contemporary choreographers?

MN: We did not limit ourselves to historical treatises in which Baroque dances were notated but linked these to the research and artistic projects of the 1970s and 1980s in which the Baroque language of dance was rediscovered and deciphered. This process of transferring a notation language conceived in the 17th and 18th centuries to the bodies of contemporary dancers was accomplished by choreographers, dancers, and researchers at a particular historical moment in France. In many ways, the advancement from research to the actual staging of Baroque dances in the 1980s created the basis for our current perception of Baroque dance. The emergence of Baroque dance on stage and the development of contemporary dance in France are also inextricably related.

Francine Lancelot (1929-2003) was among the pioneers in the research and revival of so-called historical dance. She came across the early dance treatises, such as Orchésographie by Thoinot Arbeau (1589), Le Maître à danser by Pierre Rameau (1725), and Chorégraphie by Raoul Auger Feuillet (1700), calling attention to primary sources for the coming generations of researchers and channeling her studies into artistic production. She founded the company Ris et Danceries, contributing to the diffusion and growing artistic recognition of so-called Baroque dance, which she preferred to call belle dance. Together with Sir William Christie, she worked on the restaging of Lully’s opera Atys in 1986, one of the unquestionable landmarks in the revival of what we today call Baroque dance.1

Lancelot was among those who transmitted the idea of so-called Baroque dance to dancers trained in the 1980s, and this effort lent itself to multiple interpretative possibilities. Now, forty years after the resurgence of performative and research interest in Baroque dance, we observe a new generation of dancers whose bodies are different. They are trained broadly, not only in the Eurocentric classical system or modern dance’s release techniques from the 1980s, but also in alternative somatic techniques. Regarding the technique of the body, the exhibition points to the future, namely to how the interpretation of Baroque dance technique, created about three centuries ago and fixed in the 1980s revival, is changing before our eyes thanks to choreographers and dancers of newer generations.

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

TS: Finally, can we turn to the section of the exhibition that you call “Cabinet de curiosités, sans objets,” organized as a dynamic and ludic montage of short answers to a set of questions you posed some leading specialists on Baroque dance and culture? What is the Baroque for you?

MN: The Baroque is an audacity in thinking and an aesthetic category that traverses history. It is a permanent invention of its limits and its contents.

The exhibition, Déplier Baroque, was held at the CN D from 17 November to 17 December 2022. The exhibition brochure is available for download here.

Déplier Baroque, photo © Marc Domage – Centre national de la danse.

1. For more information and writings on different aspects of Lancelot’s work, visit the CN D’s web pages devoted to her.↑

Responses