Petipa and Nureyev in Pandemic Times

Petipa and Nureyev in Pandemic Times

by Tatiana Senkevitch (Paris, France)

La Bayadère, Act II, Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, 1901

THE artists of the Paris Opera Ballet and their public gasped in despair when a block of performances of Rudolf Nureyev’s La Bayadère scheduled for December 2020 at the Opera Bastille was cancelled—along with the extended closure of other cultural institutions in France—due to the second wave of Covid-19. Rehearsals took place up to the last moment, but the public never saw the performance live, or, more precisely, the performance never encountered the public. In the spirit of the times, a live performance was held before an empty house for digital distribution.

Three pairs of étoiles, Dorothée Gilbert and Germain Louvet, Amandine Albisson and Hugo Marchand, and Myriam Ould-Braham and Mathias Heymann—along with Valentina Colossante and Paul Marque—took turns in the lead roles for the three acts of the ballet. In accordance with current health regulations, a digital recording of La Bayadère extended the ballet’s splendor to more viewers than any theatre could ever hold. Dancers performed their bows at the end of each act, as if in response to imaginary applause from the public. Even a surprise nomination of a new étoile, according to the tradition of the Opera, took place at the very end of the performance. The fortune of becoming an étoile in the days of the pandemic fell on Paul Marque, nominated for his variation of the Golden Idol. A certain appearance of normalcy in the life of the dance company was preserved. One can only speculate what Nureyev would have thought of performing without a public, and of dancing in general in the time of the pandemic. What would he have done or wanted to do under these difficult circumstances?

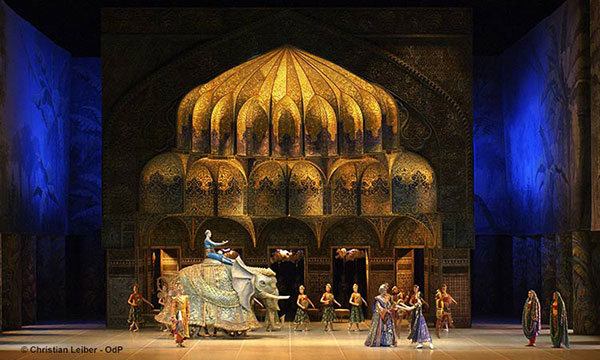

Rudolf Nureyev added La Bayadère to the repertoire of the Paris Opera Ballet in 1992. The opening night of the performance was on October 8; he had only three more months to live. On that night, the public bowed in admiration to the beauty of the ballet and to the defiant stance of the legendary dancer-choreographer, who pushed the company to a new level of excellence and whose appearance that night left no hope for his admirers. With the cinematic sets of Ezio Frigerio and striking costumes of Franca Squarciapino, La Bayadère became a signature production of the Paris Opera Ballet, taking its place of honor alongside other ballets from the treasury of the Mariinsky tradition restaged by Nureyev in Paris.

La Bayadère, Act II, Paris Opera Ballet, photo Christian Leiber

In its fabulous setting of a once-upon-a-time Hindu principality, the ballet narrates a story of love, betrayal, power, and vengeance. Marching to the drums of his time, Marius Petipa created his first version of the ballet in 1877, at the peak of the nineteenth-century craze of Orientalism. Taking inspiration from a bayadère’s story that had been circulating in different versions on the European stage since the late eighteenth century, Petipa, already at the zenith of his fame in Petersburg, created a magnificent tableau worthy of his regal patrons in Russia. The looming presence of Verdi’s Aida, mounted in Russia on the stage of the Mariinsky in 1875, and for which Petipa had composed dancing scenes, was reflected in the four-act structure of La Bayadère, the sumptuous court procession of the second act, and the rivalry of two female characters over the elegant warrior. The third act, The Kingdom of Shades, demonstrated Petipa’s incomparable intuition for a purely balletic action in which dance speaks in its own phantasmatic orthography.

La Bayadère, Act III, Paris Opera Ballet, photo Christian Leiber

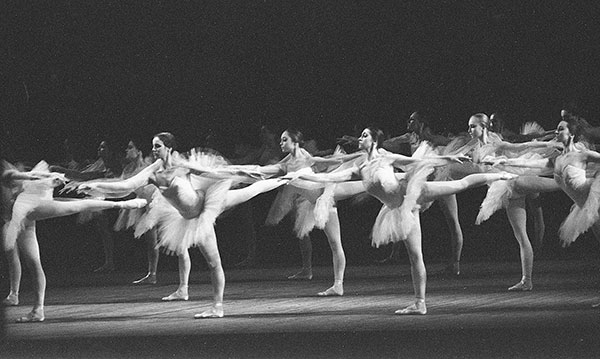

To recall the essentials of this act: the remorseful Solor, grieved by the death of his beloved bayadère Nikiya, whom he has betrayed by conceding to a socially elevating marriage, seeks solace in opium, attaining a vision of his beloved. In this vision, presented as if seen through the optical device of a smoky filter, a line of depersonalized female figures (sixty-four in the 1877 version) descends one by one from an elevated structure upstage in a synchronized chain of steps accompanied by delirious music for about a dozen minutes. The dancers, all enveloped in white tutus and transparent scarves attached to their headpieces, appear as a poetic indolence and a mechanical multiplication of the perished Nikiya at once. The third act, conceived by Petipa after seeing a cloud of angels in a lithographic Bible illustration by Gustave Doré, creates a proto-cinematic vision of the supernatural. The act of the shades turns the materiality of the dancers’ bodies into a continuous moving picture created by fluttering, monochromatic images of dancers in arabesques traced by light.

In recent years, academic studies of Petipa’s heritage have shed new light on the evolution and stage transformations of La Bayadère that had already begun to unfold in Petipa’s own time. Although the designation “after Petipa” is rightly attached to Rudolf Nureyev’s staging of La Bayadère at the Paris Opera, it is worth recalling that the legendary dancer’s visions and memories of this ballet had already passed through the thick optics of history. Petipa’s La Bayadère as known to Nureyev was a Soviet version of the grand ballet staged by Vakhtang Chabukiani and Vladimir Ponomarev in 1941. Vakhtang Chabukiani, then a thirty-one-year-old virtuoso dancer, highlighted the ballet’s leading male part both technically and dramaturgically as well as bringing more airy jumps to the female parts. Vladimir Ponomarev, fifteen years older than Chabukiani, had danced at the Mariinsky theater since 1910 and knew the style of the late Petipa’s ballets by heart. He helped to attune Petipa’s signature moves to the new technical capacities of dancers trained in the Soviet Union. This 1941 version, shown on the Kirov stage a mere few months before Germany launched its war against the Soviet Union, gingerly weaved dance and plot. Since the early 1930s, the demand to stage ballets that were ideologically suitable for the construction of the Soviet state had threatened to erase La Bayadère’s exotic story from the repertoire of the Kirov. Chabukiani and Ponomarev’s version eluded the constraints of the Stalinist state and La Bayadère acquired considerable value as part of the nation’s cultural heritage that the Kirov ballet was supposed to guard.

La Bayadère, Act III, Kirov Ballet, late 1980s, photo Svetlana Shevelchinskaya

The Kirov version of 1941 crystallized the three-act structure of the ballet, ending with the vision of the shades and dispensing with the fourth act in which Nikiya saves her beloved from the ire of the gods who reduce the temple to rubble. Chabukiani and Ponomarev moved some dances from the fourth act to the second while, for various reasons, the sets for the ruination of the temple scene gradually became obsolete. The circumstances that caused the loss of La Bayadère’s fourth act are well explained by the experts on Petipa’s oeuvre. Lately, the fourth act has reappeared in several contemporary versions of the ballet, including those by Natalia Makarova, Yuri Grigorovich, Sergei Vikharev, and Alexei Ratmansky. In the meantime, though, the three-act structure of the ballet became canonical in its own right, as it demonstrated how a late nineteenth-century ballet that pinned together a naïve plot with colorful ethnic dances had already anticipated the aesthetics of an abstract “white ballet” with its distinctive formal organization. The Kingdom of Shades, a delirium vision caused by opium, became a linchpin of the repertoire exported to the West by Soviet ballet companies from the late 1950s onwards. In many ways, it was the balance between the picturesque and the exotic in the story, and the poignant academism of The Kingdom of Shades as enlivened by the technical virtuosity of the Kirov dancers, that saved La Bayadère for posterity.

La Bayadère, Act III, Kirov Ballet, late 1980s, photo Svetlana Shevelchinskaya

The dances of the shades in La Bayadère’s third act are transcendent of both the ballet’s quasi-oriental plot and of any specific ideological underpinning. The Kingdom of Shades—a monochromatic hallucination in movements—was on the list of performances that the Kirov ballet presented in Paris and London during its 1961 tour of Europe. Nureyev, twenty-three years old at the time, shone especially bright in the third act of this ballet at the Palais Garnier on May 19, 1961. His appearance in the Grand Pas showcased a new artistic nerve and power in the male dancer, completing the lyrical ambiance created by evanescent figures of bayadères clad in white tutus. The supernatural beauty of the third act, the power and virtuosity of Nureyev and his stage partner Olga Moiseeva, along with the magnificent corps de ballet, left the public in awe that day. Nureyev considered the third act of Petipa’s La Bayadère a masterpiece, raising dance to the level of the sublime.

La Bayadère ominously turned into the last ballet staged by Rudolf Nureyev for the Paris Opera. Choreographing and directing a production of this scale required a supernatural effort for the terminally ill dancer. To stay true to the choreography, Nureyev added Ninel Kurgapkina, the prima ballerina of the Kirov, to his French team of coaches working on the staging. Kurgapkina, Nureyev’s trusted friend and partner, remarked that he strove to stay very close to the version that they both had danced in Leningrad, adding more technically challenging male solos and changing some details in the ballerinas’ variations. In her recollections, Kurgapkina, who lived in Nureyev’s apartment on the Quai Voltaire while working on La Bayadère, also noted that in her view, Nureyev had never truly left Petersburg-Leningrad, continuously staging, from his memory, ballets he had danced while there.

Staging a Russian repertoire for the Palais Garnier—and many other theatres around the world—became a leitmotif of Nureyev’s life. Working on and with dance was his ultimate modus vivendi, and he recognized only one motherland for himself, that of the stage. In La Bayadère, the theme of death is explicit, though staging a ballet about death was, for the dying Nureyev, an act of keeping his world alive. Even as his health deteriorated to the degree that he could no longer dance himself, he wished to live dance in any way possible. Learning the difficult craft of conducting was also a way to approach dance. As his biographer, Ariane Dollfus, writes in her Noureev, l’insoumis, the dancer asked Roland Petit to invite him to conduct Stravinsky’s Petruchka in Marseille in the last year of his life. Nureyev escaped the implacable fear of ageing that plagues any dancer by creating a new goal for himself. He wanted to return to the stage of the Mariinsky, his alma mater, and at fifty-one he achieved this goal. He did not wish to retire. Perhaps he had heard that Petipa, after being dismissed from his leading position at the Imperial Theatre in 1903, became a grudging old man who suspected everyone, even his own children, of disloyalty.

Dance is a sort of delirium, as the “white acts” in the old ballets about death powerfully demonstrate. In 2020, Nureyev’s version of La Bayadère, a ballet that had marked the first step on his path to fame, appeared tinged with this melancholy of absence or departure when it was shown in a digital version in front of the black hole of an empty theatre. The excellence of the dancers, along with their eagerness to perform in spite of the closure of the theatre, could not overcome the silence of the public, always a living nerve for a live performance, though a filmed ballet can surely be a worthy addition to a living theatrical experience.

For Nureyev, the La Bayadère of 1992 was an act of reconciliation with a fleeting life, with his past and precarious present. The ballet ends with Nikiya’s final pose in attitude, her finger pointing up to the heights indicating the ensuing atonement. It is a triumph of her love and, ultimately, of dance, as conceived by Petipa. For Nureyev, this finale became also a gesture of poetic redemption. With La Bayadère, he accomplished his mission of delivering yet one more of Petipa’s masterpieces to the French public. The Paris Opera production acquired more opulence, yet it preserved the distinct lyricism of the “Soviet” third act.

With the staging of La Bayadère, Nureyev forged his last cohort of étoiles—including, among others, Laurent Hillaire, Isabelle Guérin, Elizabeth Platel, and Winfred Romoli—who still keep carrying his torch of love for dance. The ballet allowed Nureyev to work again from his memories: those of Leningrad, of the Mariinsky and its tradition, of his cherished teachers, of his controlling directors and pestering administrators, and of his favorite colleagues. Perhaps, these also included the memories of his dancing the role of Solor in front of his parents, who had traveled a long way by train from Ufa to Leningrad in October 1959 to see their son on the fabled stage of the Kirov, however unsentimental about his Soviet past Nureyev might have appeared in interviews.

La Bayadère remains wrapped in veils of memory and history. The ever-growing corpus of the “after Petipa” works, in which the newer versions stand next to the revivals of the originals, form a template of knowledge on dance, a continuum of balletic culture that prevails over the distinctions between the schools and interpretations, and even in the face of global calamities such as the current pandemic.

Les Épreuves de Damis, Hermitage Theater, St Petersburg, December 2020, photo Alexei Bronnikov

At the end of 2020, Petipa marked his unfading presence in the life of dance—if only, for the moment, a digitally transmitted dance—not just through La Bayadère at the Paris Opera but also in St Petersburg. His one-act ballet, Les Épreuves de Damis ou Les Ruses d’amour, set to the music of Alexander Glazunov, was conceived as a light genre piece in the style of the eighteenth-century French comédie sentimentale and graced by decors and costumes in the manner of painters Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Lancret. The ballet premiered on the stage of the Hermitage Theatre, the imperial family’s private theatre at the time, on January 17, 1900. To revive the ballet that, unlike La Bayadère, had a short stage life, the choreographer Stanislav Belyaevsky used an academic source, namely Stepanov’s notations from the Sergeyev Collection at Harvard University. The ballet premiered at the Hermitage Theatre on December 21, 2020 before a tiny live public, consisting mostly of sponsors and critics.

Les Épreuves de Damis, Hermitage Theater, St Petersburg, December 2020, photo Aira

Nureyev’s La Bayadère, Petipa’s grand ballet, and Les Épreuves de Damis, the master’s light-hearted pastoral, both staged by former dancers of the Mariinsky, “the house of Petipa,” were among the last theatrical events of the stringent 2020. Although of different genre and historical significance, these two performances signaled the enduring capacity of Petipa’s world to persist and adapt to new moments in history, even to moments when live theater falls silent.

Les Épreuves de Damis, Hermitage Theater, St Petersburg, December 2020, photo Alexei Bronnikov

PICT would like to say a very special thank you to Stanislav Belyaevsky (Helsinki, Finland) and Svetlana Shevelchinskaya (St Petersburg, Russia) for permitting us to use stunning photos from their private archives, published here for the first time.

Responses