The Borodin Quartet on Tour

The Borodin Quartet on Tour

(Version française ici)

by Valentin Berlinsky (Moscow, Soviet Union – Russian original)

by Maria Matalaev (Paris, France – French translation, compilation, editing)

by Angela Dickson (London, UK – English translation)

Editor’s Introduction

This piece was originally published as a chapter of the 2018 book, A Quartet for Life, recounting the life of Valentin Berlinsky (1925-2008), founder of the legendary Borodin Quartet. The book is based on primary sources such as diaries and interviews, compiled and edited by Maria Matalaev.

The Borodin Quartet, it has been said, was to the string quartet what Richter was to the piano, Oistrakh to the violin, and Rostropovich to the cello. In 1955, the Quartet became the first Soviet chamber group to be heard beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. It performed the traditional quartet repertoire and presented Dmitri Shostakovich’s chamber works to the West as they were completed. It also gave the first performances of many works by Soviet composers such as Alfred Schnittke, Boris Tchaikovsky, Lev Knipper, and Mieczysław Weinberg.

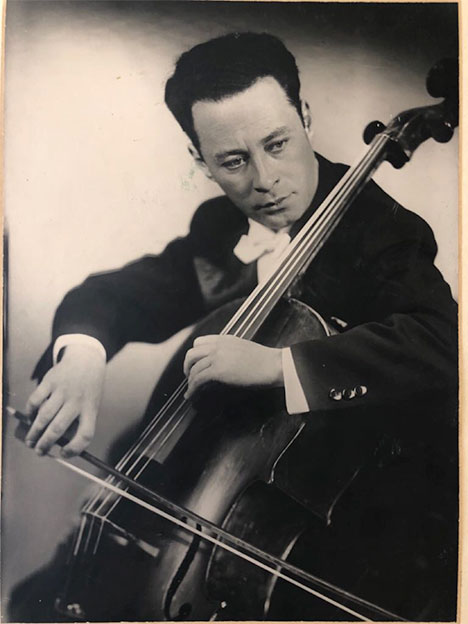

The Quartet’s exceptional longevity (1945 to the present) and its ever-renewed level of perfection were due in large part to one man: Valentin Berlinsky. In addition to founding the first Soviet ensemble to go abroad, touring more than six hundred countries, and leaving a colossal recording legacy, Berlinsky was, above all, a cellist of exceptional sensitivity. He was a friend of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Maya Plisetskaya, scholar Andrei Sakharov, and chess player Garry Kasparov. He was an uncompromising musician and a patriot.

In the book, Berlinsky recalls his Siberian childhood, the years of war, his conservatory years in Moscow at the center of the Soviet cultural elite, the influence of Dmitri Shostakovich, the friendship of Sviatoslav Richter, and, most importantly, his tireless work, leading to the constitution of a true quartet tradition in the USSR and an enduring influence throughout the world. A discreet man and a remarkable personality, Berlinsky reveals himself as an ardent servant of “the living and immediate birth of Music, the complex interaction of sounds as it is written in the text.”

The following chapter recalls the Quartet’s first tour abroad. To work as a stand-alone piece, the original has been slightly modified. For a full account of Valentin Berlinsky’s life and work, we enthusiastically recommend the book itself. The text is reproduced courtesy of Kahn & Averill; all illustrations and documents are reproduced courtesy of Maria Matalaev.

5th December 1953. Saturday. Minsk. First concert today. We played the Andante Cantabile and three pieces from Tchaikovsky’s Album for the Young (Morning Prayer, Nanny’s Story, Polka) in Rostik’s arrangement for quartet. In the first half, we accompanied MD (Alexandrovich1). Some of it wasn’t too bad, although it’s been a long time since he was last on stage, and singing with a new quartet didn’t give him enough freedom or confidence.

5th December 1953. Saturday. Minsk. First concert today. We played the Andante Cantabile and three pieces from Tchaikovsky’s Album for the Young (Morning Prayer, Nanny’s Story, Polka) in Rostik’s arrangement for quartet. In the first half, we accompanied MD (Alexandrovich1). Some of it wasn’t too bad, although it’s been a long time since he was last on stage, and singing with a new quartet didn’t give him enough freedom or confidence.

Minsk is a lovely town, with new buildings and broad streets.

12th December. Sunday. Babruysk. Nine hours on the road from Minsk to Gomel, where we played a concert in a “Lenin” club. Gomel is a devastated town and is being restored much more slowly than Minsk.

All MD’s concerts are sold out. Tickets are being sold outside at 75-100 roubles each, and girls are ready to give anything for a seat…

We had no name, no guaranteed future, not even a settled present. We made ends meet by playing at funerals, in schools, at factories and clubs. The handful of concerts we had done had demonstrated that, for audiences and for us, it was important that we had a recognisable name.2 Obtaining one at that time was as difficult as getting an aristocratic title. We wanted Tchaikovsky Quartet, but at Stalin’s funeral,3 Oistrakh told us that the Ministry of Culture had decided to form a “super” quartet, with the intention of creating the best such group in the world. This as yet non-existent quartet had already been named after Tchaikovsky. The vanity of power and patriotism spawn such ideas… In the end, this quartet consisted of Julian Sitkovetsky, Anton Sharoyev, Rudolf Barshai, and Yakov Slobodkin. They were the first group to embark on tours abroad. This opened the way for others. But it didn’t last long: eighteen months later and it was no more. But the name had been used!

We had no name, no guaranteed future, not even a settled present. We made ends meet by playing at funerals, in schools, at factories and clubs. The handful of concerts we had done had demonstrated that, for audiences and for us, it was important that we had a recognisable name.2 Obtaining one at that time was as difficult as getting an aristocratic title. We wanted Tchaikovsky Quartet, but at Stalin’s funeral,3 Oistrakh told us that the Ministry of Culture had decided to form a “super” quartet, with the intention of creating the best such group in the world. This as yet non-existent quartet had already been named after Tchaikovsky. The vanity of power and patriotism spawn such ideas… In the end, this quartet consisted of Julian Sitkovetsky, Anton Sharoyev, Rudolf Barshai, and Yakov Slobodkin. They were the first group to embark on tours abroad. This opened the way for others. But it didn’t last long: eighteen months later and it was no more. But the name had been used!

This was in 1953. We then thought we might take advantage of the forthcoming Glinka anniversary and use his name. The Glinka Quartet… a hugely important Russian composer, inventor of Russian opera and of the music profession in Russia: it had a good ring to it. We received advice from Vasily Petrovich Shirinsky and first made an appointment with Khrennikov4 to obtain his signature. He was mollified by the thought that this was all we were asking of him and promised to write a letter in our favour. Six months later, the letter was ready. We obtained signatures from Shostakovich and many others. We were finally in a position to send the letter to Anisimov, the Minister of Culture, and after six more months, he invited us to come to see him. He was friendliness itself, but he considered that the name Glinka should be used by a larger group—a choir, an orchestra, or a conservatory. Shirinsky had warned of this, and we had come prepared. We suggested Borodin,5 who wrote two magnificent quartets, excellent examples of the genre. He may well have seemed less important than Glinka in the minister’s eyes, though he was just as Russian, so he could safely grant us the name. This is how we became fervent propagandists for the name of this marvellous composer, at the cost of just an endless round of administrative procedures, letters to various organisations, and two years of waiting. This marked a new stage in our life as a quartet. Tours abroad could now start.

In June 1955, our first trip abroad as the Borodin Quartet took us to East Germany. We were due to give a series of concerts to commemorate the tenth anniversary of victory over the Nazis, with a group of Soviet artists: Pavel Gerasimovich Lisitsian,6 accompanied by his pianist Mikhail Erohin, who had extraordinarily big hands (he could play a twelfth with one hand!), as well as violinist Mikhail Vaiman7 and pianist Maria Karandashova,8 the famous duo from St Petersburg. Vaiman, who died young, is practically unknown now, which I find hard to understand. He had a wonderful sound.

This trip was followed by many others, to Czechoslovakia, Romania, Moldova, Siberia, and elsewhere. In 1958, we crossed the Iron Curtain for the first time and went to a capitalist country, Italy, where we introduced ourselves to great acclaim. Then it was Sweden and Finland, Germany, and our first recordings abroad. We were becoming part of the “elect” who went back to the USSR crowned with the halo of success abroad, and, a sure sign of this success, dressed in better suits.

A sad interlude: on 23 May 1959, we played at the Conservatory’s Small Hall: Shostakovich’s third quartet and the piano quintet with Oborin. I felt ill at ease on stage and I was uneasy, as happens when one foresees a misfortune. When I returned home, my wife and relatives were waiting for me: my father had died in hospital during our concert.

I have spent a large part of my life on tour. I love change, new impressions, meeting new people. As a quartet, we visited many towns in the Soviet Union and travelled round the world several times. I managed to keep some notes in my diary. On our first tour abroad, we were struck by the standard of living in the West, which differed from ours in the consumerism of its culture and the population’s apparent prosperity. The excessive contrast between the sentimentalism of our idealism and real life was very conspicuous. It was such an offence against Russia, its people, history, and culture, that even today I have difficulty accepting it.

But for us, the essential things were elsewhere. In a space that politics cannot touch, music can bring people together in concert halls.

I have always held that tours are different from other types of travel. What I remember most is not foreign landscapes but concert programmes, hunting for playing partners, chance encounters—the rest is just the backdrop to the musical events.

14th October 1969, 2am. First, impressions of the concert.

14th October 1969, 2am. First, impressions of the concert.

Queen Elizabeth Hall. 1000 seats. Very good acoustic. Hall almost full. We played Britten, Mozart, Beethoven.

England is one of the few countries where it’s unthinkable to start the concert even one or two minutes after the official time, as it is broadcast live on the BBC. We were literally pushed onto the stage.

“So we’ve arrived at the scaffold” I said to Aliochka (our impresario) when our minibus stopped outside the artists’ entrance at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The scaffold. That’s the abiding image I have of today’s performance, and all because of Britten. His second Quartet. We have played it in this country before, in 1962 at the Edinburgh Festival. Before that, we played it once in Moscow. That’s it! We were supposed to play it in Kuybyshev, but Mitia was ill, the tour of the Union was cancelled, and we’ve done practically no rehearsal in preparation for this tour. Yesterday, in rehearsal, we considered replacing Britten with Borodin. Rostik started negotiations about this, but the only outcome was outrage. An insult to the nation! (Even though Britten left the country on the day of our concert, which had been planned for months…)

We opened the concert with it. Rehearsal during the day, and before we went on stage, literally until the third bell rang. We gave it everything we could. Then Mozart. That was difficult. We didn’t have the strength for the second half (Beethoven op. 131).

Friends from various countries came to hear us: from Italy, Holland, and the USA (Texas). It’s a tradition: if we’re on tour in Europe, friends, acquaintances, and fans from neighbouring countries come to hear us.

15th October. The review in the Times the morning after is good but not enthusiastic. It appears there is always a “but” in English reviews… No strength to pick up my cello today. I expended so much energy in yesterday’s concert, and slept so little, that I now feel completely shattered.

17th October. Yesterday we arrived in Monmouth after four hours in the car. South Wales is exactly as I imagined. Mountains, dense forests. Very picturesque. We’re staying in a little hotel called the White Swan, with plywood walls. We can hear our neighbours breathe. The concert was at the school. Good audience. We played two or three things not too badly. After the concert, there was a little party and a meal at a Chinese restaurant. The Chinese food was excellent: tasty, plentiful. Monmouth is a small town, or rather a village, though the shop windows are similar to those in the cities.

The journey was hard, as it often is in this country. We have a minibus, which is comfortable and fairly pleasant. Our driver Andrew does a good job. He’s tall and thin, about twenty-five, with a long face and glasses. He doesn’t smoke, but as for drinking, he’s pretty keen if the opportunity arises after concerts when he doesn’t need to drive. And the opportunity did arise: after a concert in Minterne, we ended up leaving for London at about four in the morning. We drove slowly in the fog, and the journey took nearly four hours…

Another concert. Cardiff. Lovely town, the concert was at the museum. In the foyer, there are sculptures by Rodin. Lovely acoustic and a generous audience. We have played here before, three years ago. Programme: Prokofiev 2, Schumann’s “Clara Quartet,”9Debussy. Rostik started the scherzo of the Debussy on his own, without me. It was very funny: his D octave came in all by itself, then I joined him. Something in the ensemble just didn’t work. What saves us in these difficult situations is our professionalism and our performance experience. Ten years ago, it was all much more difficult, but also much simpler! Our physical feelings are evidence of this, but we’re no less nervous before concerts; quite the opposite, in fact. This increases as we get more dissatisfied and demanding with ourselves.

19th October. First day off in ten days. Freedom is a relative term, though: I have done an hour and a half’s practice, although I didn’t really want to: the cork was out of the bottle at that point!

We’re playing Britten again tomorrow, in Manchester. Yesterday’s concert was the best we’ve done in Britain, despite a very stressful day! We started in Cardiff at 7am. At 8, our bus left for London. We arrived at the Prince of Wales without any trouble, then went to our rooms, hung up our concert dress, then went… to a Chinese restaurant. Mr Fu Tong’s—delicious food, quick service, clean surroundings. A bit expensive. A long soup and rice for 15 shillings (lunch at the Embassy canteen costs 6). At half past three I tried to sleep, tossed and turned until 4, then got up and did some practice. At 5:45 we got back in the bus and drove for an hour to Mill Hill. We’ve played there twice before. It’s the best audience in Britain! A 500-seat hall, and about 80 chairs on the stage.

Programme: Ravel (yes indeed!). We started the concert with this (and it went very well!), then Shostakovich 9, and Beethoven op. 131 in the second half. It was a great success. A shame it wasn’t recorded. We were inspired by I know not what, and preserved our energy until the last chord of the Beethoven. But after that we were completely wrung out. My suit was completely soaked.

And this morning I got up at 7 and waited for the phone to ring. How many times have I done this over the years, in how many different countries, and I am still stirred by the prospect of a call from my grumpy one…10

21st October. We left for Manchester yesterday at 9am. Six hours on the road is exhausting. Another Chinese meal, forty winks, and then Britten. We played the London programme again. I think we played the Beethoven and Mozart better than we did in London… After the concert, to Burnley and the large house of a rich man who is also a music lover and amateur cellist. He has seven daughters. He has a farm, cows, horses, and a large house with guest rooms. I got up at 10am. That’s a first for this trip! Our last concert in this country. After the concert, Mitia, Slava, and I are taking the night train for London. Rostik is leaving tomorrow morning with the driver. He loves big houses and can’t stand hotels. I’m the opposite…

26th October. Paris. 27th, 28th, 29th—rehearsal of Beethoven’s quartet op. 130 (for another time). I’m going nowhere and feel defeated… Paris is miserable this time…

30th October. Aunt Macha is dead. I called them in the evening, after television had finished. I don’t know why, but it’s very hard to deal with. 78 years old. It’s not bad, these days. But it’s news that weighs upon me, and it does make my heart ache…

I have lived for a long time; I know how these things go. But I have never managed to reconcile myself to the death of someone I loved. Mourning always awakens a feeling in me that I find hard to explain, but which is associated with hardship and, above all, rebirth. It’s as though I wanted to live more fiercely and more intensely in order to prolong the life of the one who has died.

I have lived for a long time; I know how these things go. But I have never managed to reconcile myself to the death of someone I loved. Mourning always awakens a feeling in me that I find hard to explain, but which is associated with hardship and, above all, rebirth. It’s as though I wanted to live more fiercely and more intensely in order to prolong the life of the one who has died.

In the 1960s, we had over 400 works in our repertoire. Later, we decided to limit ourselves and focus on the most significant works. Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms; and of course Borodin and Tchaikovsky representing Russia. Thereafter, the selection narrowed down naturally. To keep 400 works at a professional level of quality, I implemented a ranking system:

+ for works that we could play today;

++ for works that would need 3-4 days of rehearsal to get up to standard;

+++ more than 10 days;

++++ at least a month;

+++++ works that we shouldn’t play anymore.

Not many works were assigned five crosses, but they were to be avoided permanently. Some quartets simply didn’t work for us. For instance, the music of the great composer Sergei Ivanovich Taneyev was not very popular. We tried to include his quartets in our programmes, but audiences were indifferent to them. I think it was our fault: we probably didn’t get to the heart of his musical ideas. The composer is very good, but our performances showed that our audiences, for whatever reason, didn’t take to his music. We probably shouldn’t have stopped playing his works. It’s sometimes very difficult to overcome the inertia of one’s own thoughts, and even more so the thoughts of the audience.

In the 1960s, the Quartet had a very busy concert schedule. We gave over 130 concerts each year on average. If we only did a hundred, we thought it was a quiet season. The 1961/62 season contained 146 concerts. No other quartet had such a busy schedule. At that time, we were all over the world, with a very tight tour schedule and a feeling of great responsibility.

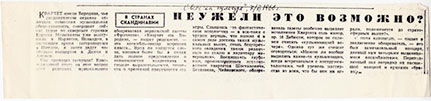

The Borodin Quartet’s tour of Japan has just ended. Our correspondent V Drozdov reported in a telephone call: “Once again, one of the largest halls in Japan was full, and music lovers were even turned away. Some fans who wanted to hear these Soviet musicians were unable to enter the hall, which holds 3,000 people. Many were hoping to obtain a ticket at the last minute, but there were no tickets left. The hall was full. On the programme: quartets by Borodin, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Beethoven, Haydn.”

The Borodin Quartet’s tour of Japan has just ended. Our correspondent V Drozdov reported in a telephone call: “Once again, one of the largest halls in Japan was full, and music lovers were even turned away. Some fans who wanted to hear these Soviet musicians were unable to enter the hall, which holds 3,000 people. Many were hoping to obtain a ticket at the last minute, but there were no tickets left. The hall was full. On the programme: quartets by Borodin, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Beethoven, Haydn.”

A phenomenal success! Inhabitants of Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Nagoya had the opportunity to get acquainted with the art of the string quartet. Sumi Saburo, a well-known professor at the Tokyo Conservatory, declared to our correspondent: “The best quartets in the world have played in Japan, in this very hall, but what we heard this evening has surpassed all others. The Borodin Quartet is the best chamber group in existence.” The Japanese press was breathless with praise: “The professionalism of our visitors,” remarks the Mainichi newspaper, “is beyond criticism; they play like one person, with perfect sound. We already know what quartets around the world are capable of, but the playing of the Borodin Quartet is something entirely new, truly never heard before.”

— Sovetskaya Kultura (“Soviet Culture”), 12th April 1966.

“If there are any miracles in music, miracles of absolute perfection, the Borodin Quartet from Moscow is one of them.” — “It was magic, a real discovery, a miracle.” — “This quartet is without a shadow of a doubt the best in the world.”

“If there are any miracles in music, miracles of absolute perfection, the Borodin Quartet from Moscow is one of them.” — “It was magic, a real discovery, a miracle.” — “This quartet is without a shadow of a doubt the best in the world.”

This is what newspapers in Germany, Sweden, and the United States have said about the Borodin Quartet. Its members, R Dubinsky, Y Alexandrov, D Shebalin, and V Berlinsky, have won the hearts of many lovers of chamber music. The Quartet recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary. In this time, is has acquired the status of an “ultra-high quality” quartet, and tirelessly promotes Russian, Soviet, and foreign chamber music. Its repertoire includes works by Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and many others.

The Quartet is currently embarking on its third tour of the United States and Canada. They are going to play in New York, Toronto, Montreal, Pittsburgh, San Antonio, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vancouver, and Detroit. We hope our American and Canadian colleagues will go to their concerts and give this quartet the appreciation their art deserves.

— Z Muratov, “Third Time Overseas,” Voice of the Homeland (a monthly published abroad), 4th December 1966.

1. Mikhail Davidovich Alexandrovich (1914-2002), a Latvian tenor and cantor who was known for his classical and popular repertoire and whose voice was especially suitable for recitative, Hebrew chants, and Jewish songs.↑

2. These days, chamber groups choose a name before they have even learned their first work, but in the mid-20th century, the Soviet Ministry of Culture authorised groups and assigned names one by one.↑

3. One of the most remarkable episodes in the first years of the Quartet occurred in March 1953, when the Borodins played at Sergei Prokofiev’s funeral before spending several days “on call” at the funeral of Joseph Stalin, who had died on the same day (5th March 1953). Around fifteen people attended Prokofiev’s funeral, while the whole country descended on Moscow to pay their respects to Stalin’s remains. Dubinsky tells the story in Stormy Applause (Hill and Wang, 1989), his memoirs of the Soviet period:

“Over and over again, we played Tchaikovsky’s Second Quartet. Everything began to appear unreal, repeating itself as if in a strange dream. And again, as on the day before, people walked in with their heads bare, looking at the coffin with the same expression of grief and humility. Toward evening I fell asleep with my violin in my hands. Alexandrov nudged me. I fell asleep once more and he nudged me again. ‘Don’t fall off the chair,’ he whispered. ‘We have to play now.’

“The third and final day came. We still hadn’t had anything to eat. Contact with the outside world was maintained only by those brave people who could make their way back after going out into the streets. Their tales were spread in terrified whispers. They said that people kept coming and coming, besieging trains from Leningrad and other cities to Moscow. The city itself was surrounded by troops with heavy trucks. They blockaded all the streets leading to the Hall of Columns, leaving only Pushkin Place open. Through it, the stream of people was shoved into Pushkin Street and pushed into the Hall of Columns. An enormous jam developed from which there was no exit, and new people kept squeezing in, tighter and tighter. At first, trucks were used to restrain the crowd. But the pressure grew even stronger and the trucks themselves were eventually swept away by the flow of people. Late in the evening, we put mutes on our instruments and began Tchaikovsky’s Andante Cantabile. We played quietly, without vibrato, the way Russian folk songs are sung. The delicate sound of the Quartet drowned in the incessant noise of the slowly moving crowd.”↑

4. Tikhon Nikolayevich Khrennikov (1913-2007), Russian composer and politician. He was secretary general of the Union of Soviet Composers from 1948 to 1991, and he was feared by Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, and above all by Alfred Schnittke. These composers were all criticised for their formalism, which was seen as too distant from socialist realism.↑

5. Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (1833-1887), self-taught Russian composer, chemist, and doctor. He was a member of the Mighty Handful group of five Russian composers and a disciple of Glinka.↑

6. Pavel Lisitsian (1911-2004), Russian baritone, soloist at the Bolshoi.↑

7. Mikhail Izrailevich Vaiman (1926-1977), Russian violinist and teacher, Meritorious Artist of the USSR. He taught at the Leningrad Conservatory and often played in a trio with Pavel Serebryakov and Mstislav Rostropovich.↑

8. Maria Vsevolodovna Karandashova (1918-1996), Ukrainian pianist who taught at the Leningrad Conservatory and often played with Rostropovich and Vaiman.↑

9. Berlinsky used this name to describe Schumann’s Third Quartet, op. 41. In the first movement, as a way to show how the first phrase of the Allegro molto moderato should be shaped, Berlinsky invented the following words: “Клара, когда же, черт возьми тебя, ты выйдешь замуж за меня!” (“Clara, when the devil will you finally become my wife?”). Schumann composed his three quartets in the space of a few months in 1842, which was a relatively happy year as he had just married Clara Wieck although her father had forbidden the marriage.↑

10. His wife, Zoya Kuzminitchna Ivanova.↑

Responses