On the Crisis of (White) Masculinity

Image: “A Bantam,” from Shadows by Charles Bennett (ca. 1856)

On the Crisis of (White) Masculinity: Victimization Discourse and Transformations in Racialized Forms of Gender Inequality

Tristan Bridges and Ian Anthony

This article examines the recurring portrayal of masculinity as being in a perpetual state of crisis over the past two centuries. In response to gendered changes initiated in large part by the feminist movement, the discourse surrounding men’s liberation in the 1970s aimed to challenge traditional notions of masculinity, and within this trend emerged a discourse of (white) masculinity as “in crisis.” We show that such discourses are in fact a perennial feature of transformations in gender relations and document their historically recycled nature. Unpacking the discursive (il)logic of its proponents’ claims, we examine what we present as twin consequences of the discourse: (1) the implicit portrayal of men as victims, and (2) the cultural distraction that deflects attention from pressing societal issues and from the ways masculinity is often entangled with those larger issues. Ultimately, we highlight the need for a critical examination of “crisis of masculinity” narratives and of the complex interplay between masculinity, power, and societal issues more broadly.

Introduction

The “men’s movement” has long referred to an awkward assortment of vastly different groups of men with ideological commitments spanning the gender-political spectrum.[1] Prompted by the feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century, a movement for “men’s liberation” emerged in the 1970s with the professed goal of challenging social and cultural understandings of masculinity.[2] That movement, however, was short-lived and soon split in support or denial of feminist claims that men’s collective privilege has worked to women’s collective disadvantage (even if men too are harmed by cultural constructions of masculinity).[3] By the 1990s, a veritable cottage industry of commentary had emerged, alleging that shifts in society had victimized men and caused masculinity more broadly to slip into a state of “crisis”— a “crisis” that was mobilized to challenge what was presented as the “myth of masculine privilege.”[4]

As both Morgan and Hearn argue,[5] “crisis” captures some element of the current cultural zeitgeist more broadly; so, we should not be surprised that alongside uses of the term to address “economic crises,” “the nuclear crisis,” “the environmental crisis,” and even “a crisis of Western civilization,” masculinity too is sometimes claimed to be “in crisis.” However, while crisis may be an apt concept to describe various contemporary phenomena and relations, a substantial body of scholarship suggests that it is ill-suited to address masculinity—to say nothing of how the discourse of “masculinity in crisis” has been mocked by the likes of screenwriter and humorist Bruce Feirstein, in his satirical Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche: A Guidebook to All that is Truly Masculine.[6]

The discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” presents men as uniquely victimized by gender relations—and some groups of men much more so than others. In contradiction to this claim, we summarize some of the gender research and theory that shows how the discourse of masculinity “in crisis” appears and reappears at historical moments during which (white) men’s collective privileges are challenged in historically novel ways. Further, we suggest that the discourse itself effectively operates as a means of reclaiming gendered and racialized forms of status and power by casting (white) men as the “real” victims of gender inequality.

(White) masculinity has recurrently been portrayed as being in a fairly ongoing state of crisis over the past two centuries. Each iteration of this narrative depicts men as “victims” of societal forces beyond their control, perpetuating a discourse that warrants critical examination. By dissecting the underlying logic of such narratives and challenging their foundational premises, we show that such claims are largely unsubstantiated. Despite the lack of empirical or historical evidence supporting these claims, however, their impact remains substantial.

We further argue that the discourse surrounding the “crisis of masculinity” shares striking similarities with narratives of “victimized masculinity” often championed by antifeminist groups. The efficacy of the discourse of masculinity “in crisis” lies, we suggest, in its subtle invocation of victimhood, which serves as a potent distraction from actual, pressing global crises and the intricate interplay between those crises and cultural constructs of masculinity.

Crisis? What Crisis?

“Crisis” can refer to more than one thing, and these multiple meanings make the concept more seductive for the purposes of proclaiming masculinity as “in crisis,” or a “crisis of masculinity” more generally. There are two sets of meanings associated with the concept, with some overlap between them. One interpretation pertains to crucial moments, pivotal points where significantly divergent outcomes are possible (such as recovery versus collapse). Another interpretation is commonly linked to periods of challenge, uncertainty, or suspense across various domains or institutions within social contexts. To clarify this distinction, Morgan proposes differentiating a “crisis in masculinity,” which relates to the former definition (a more specific issue with potential resolution), from a “crisis of masculinity,” which refers to the latter (a broader phrase marked by uncertainty, challenge, and unease).[7]

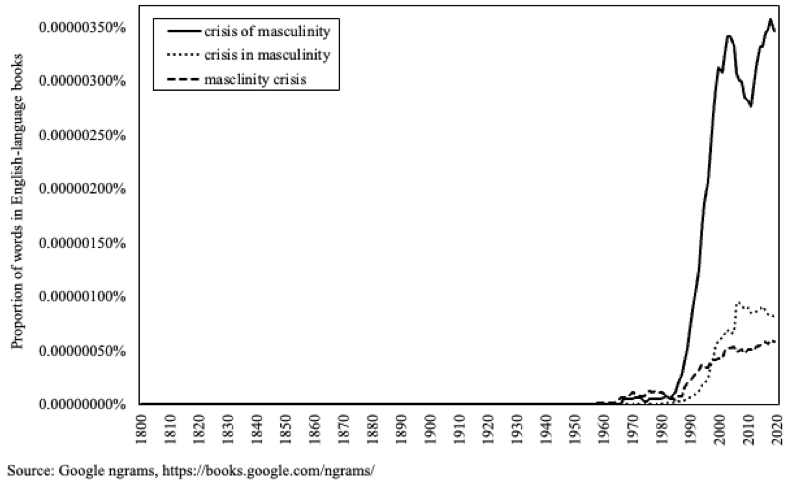

Hearn suggests that the formulation, “crisis of masculinity” (using Morgan’s terminology), is the most frequently utilized,[8] and a review of published work in English over the last two centuries supports this claim, illustrating that the usage of the formulation has rapidly increased since the last two decades of the 20th century (see Figure 1).[9]

Figure 1. Relative Popularity of “crisis of masculinity,” “crisis in masculinity,” and “masculinity crisis” in Books Published in English, 1800-2019

Figure 1 would seem to suggest that the discourse of the “crisis of masculinity” is historically young, only having become widespread since the mid-1980s. Scholarship on the topic has found, however, that the discourse is best understood as historically recycled and has appeared routinely over at least the past two centuries. While there may be greater reliance upon the actual terminology of the “crisis of masculinity” today, we show below that similar fears and discourses have appeared throughout the U.S. and Europe since at least the 1800s. While there may be more social and cultural agreement on how to label this discourse today than there was in the past, the discursive tactics and logic are far from new.

The “Crisis of Masculinity” as a Product of Modernity and Historically Recycled

The current “crisis of masculinity” is not the first time such discourses have emerged. For instance, both Bederman and Rotundo document the turn of the 20th century as a moment in U.S. history when discourses of men, manhood, and masculinity as “in crisis” were rampant.[10] At the time, U.S. society was undergoing substantial economic and cultural changes that made some groups of men’s claims to racialized and gendered privileges less secure. Class-advantaged white men’s social, economic, and cultural positioning was structurally unsettled in historically novel ways, and research on the period shows that there was a bit of a frenzy to resecure that positioning.

Charting the shifting history of manhood in Europe, Mosse also identifies the fin de siècle as a distinct moment, and in ways that are not so dissimilar to the U.S. As he writes,

On the face of it, that age [the 1870s to the 1920s] was one of great stability [for men] […]. But in reality this very society was on the offensive against new challenges that questioned some of the most important presuppositions on which it was based and threatened the image it had of itself. The enemies of modern, normative masculinity seemed everywhere on the attack: women were attempting to break out of their traditional role; “unmanly” men and “unwomanly” women […] were becoming ever more visible. They and the movement for women’s rights threatened that gender division so crucial to the construction of modern masculinity.[11]

Under such historical circumstances, research shows that (white) masculinity is often framed as in need of defense. For instance, Adorno et al.’s 1950 treatise on The Authoritarian Personality traces the emergence of a particular gendered discourse associated with the rise of fascism in cultural response to fears of effeminacy and feminization.[12] The book’s primary argument is that fascism was, in part, the product of men living stereotypes of masculinity to their logical extreme.

The same argument is made by Theweleit in his two-volume Male Fantasies, where he explores the particular configurations of white masculine identity that helped give rise to fascism through fears associated with shifts in women’s status, embodiment, and power in German society.[13] These discourses of (white) masculinity as in a particular kind of “crisis” arose during a time when men were embroiled in unceasing warfare over the course of three decades. As Barbara Ehrenreich notes in her foreword, “it is not only men that make wars, but wars that make men”[14] and, as we would add, help to forge particular discourses of masculinity as “in crisis,” with war offered as the resolution.

The historian Lynne Segal documents a similar discourse of crisis in the 20th-century U.S., noting that masculinity was transforming and routinely cast as “in crisis” between the 1950s and 1990s—though the reasons for the “crisis” differed over the latter half of the 20th century.[15] Further, Sally Robinson shows that the discourse of white masculinity as “in crisis” was everywhere in American culture from the late 1960s through the end of the 1980s and was uniquely well-suited to addressing concerns over shifts in gender relations alongside rights-based movements that put masculinity and whiteness in a new kind of historical spotlight.[16]

“Crisis,” Robinson shows, was a more effective discourse than “victimization” despite the fact that the latter was also often employed. The advantage of a discourse of masculinity “in crisis” over that of men as victims was that it was “flexible enough to accommodate a range of narratives driven by competing investments and intentions,”[17] a flexibility or “lability” that American Studies scholar Hamilton Carroll argues persisted into the new millennium.[18]

As both Robinson and Carroll show, the discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” has been consistently mobilized in response to accusations of chauvinism and to support exclusionary defenses of white men’s privilege in response to perceived threats associated with feminism and other civil rights movements.[19] Yekani explores a similar discourse in a historical analysis of masculinities in colonial and postcolonial literature, photography, and film aptly titled The Privilege of Crisis, noting that claims of masculinity as “in crisis” have tended to center the masculinities of relatively privileged groups of (white) men.[20]

The scholarship here suggests a cultural appropriation of the identitarian discourses emerging throughout the 19th and 20th centuries by privileged configurations of (white) masculinity. Whether by design or circumstance, this body of scholarship converges on the observation that the discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” has worked to recuperate racialized forms of gender hegemony precisely at moments when such systems of power and inequality were challenged in new ways. Indeed, it is precisely this quality, this unique form of flexibility that makes hegemonic masculinity hegemonic.[21]

Nonetheless, as Figure 1 shows, while discourses of (white) masculinity as “in crisis” have been persistent since the mid-1800s, they seem to have accelerated in recent history. This should not be too much of a surprise as masculinity itself is a relatively modern invention, a part of the social construction of identity inside modernity.[22] Thus, we also ought to understand the discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” as, in large part, a product of modernity. As MacInnes writes,

[T]he whole idea that men’s natures can be understood in terms of their “masculinity” arose out of a “crisis” for all men: the fundamental incompatibility between the core principles of modernity that all human beings are essentially equal (regardless of their sex [or gender]) and the core tenet of patriarchy that men are naturally superior to women and thus destined to rule over them.[23]

Historically speaking, the meaning of “masculinity” has always been subject to incredible fluidity and variation.[24] And as Connell famously argues in Masculinities, “As a theoretical term ‘crisis’ presupposes a coherent system of some kind, which is destroyed or restored by the outcome of the crisis. Masculinity […] is not a system in that sense.”[25] Thus, while there is very little evidence to endorse the notion that masculinity is (or indeed can be) in crisis, there is ample evidence supporting Edwards’ argument that “masculinity is perhaps partially constituted as crisis.”[26]

On the (Il)logic of “Crisis” Discourse and Claims to Victimization

Claims that (white) masculinity is “in crisis” are logically contradictory since masculinity is not, and has never been, the socially and culturally stable subject position that could enter into a crisis.[27] Despite this, however, we have seen how the crisis discourse emerges at key historical periods during which gender relations are undergoing transformations and racialized and gendered systems of power and inequality are being renegotiated. The discourse of (white) masculinity as “in crisis” also works to effectively claim that men are uniquely victimized by gendered forms of change. In this section, we summarize the logic of this discourse as it has appeared in recent history.

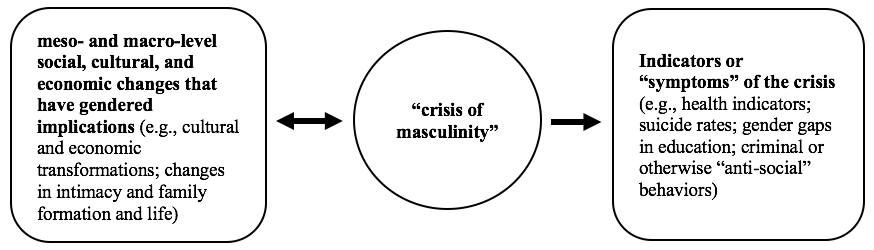

The “crisis of masculinity” thesis relies not only on certain forms of evidence, but also on a distinct discursive structure and logic. For instance, there are patterned sets of indicators (what Morgan refers to as “symptoms”[28]) that support the discourse, as well as larger social and cultural transformations that are used to structurally position (some) men as “in crisis.” We suggest that the discourse of masculinity “in crisis” generally follows the model indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Modeling the Discursive Logic of Allegations of Masculinity “in Crisis”

As we show here, the “crisis of masculinity” is a discourse that connects disparate social and cultural transformations with specific outcomes for boys and men. And while the argument appears to be relatively logical, this logical structure is routinely violated.

While the specific social, cultural, and economic transformations cited as causing the “crisis of masculinity” vary, there are some commonly referenced factors. For instance, as Susan Falludi writes in Stiffed, “The more I consider what men have lost—a useful role in public life, a way of earning a decent and reliable living, appreciation in the home, respectful treatment in culture, the more it seems that men of the late twentieth century are falling into a status oddly similar to that of women at mid century.”[29] As Falludi and others argue, three primary factors are commonly taken to give rise to the “crisis”: (1) shifts in the relative positions of women and men in social, cultural, and economic life, (2) shifts in patterns of work and the labor market, and (3) transformations in intimacy, family formation practices, and family life more generally.

Men (and often, implicitly, white men) are positioned here as uniquely victimized by larger and structural social change, with any change to their sense of themselves as “masculine” framed as being imposed from “above.” We would suggest, however, that the discourse of (white) masculinity as “in crisis” also has a reverse impact on those structural transformations, giving them new kinds of meaning and thereby establishing a reciprocal relationship with them.

It is here that we turn to what we call “indicators” (or what Morgan refers to as “symptoms”) of the “crisis of masculinity.” In order to claim that larger, structural factors victimize boys and men in historically novel ways, these factors must be connected with specific outcomes or indicators. Temporal, demographic, and episodic details are necessary, particularly in the context of larger historical data, for the argument to be something more than a mere discursive sleight of hand.

Within the discursive logic of the “masculinity crisis,” a very specific set of indicators on which boys and men tend to fare worse than girls and women are used as evidence that larger, structural shifts are being felt on the ground and shaping boys’ and men’s gendered experiences of themselves. Particularly common are lists of health indicators documenting the various ways in which boys and particularly men are collectively in worse shape than girls and women.

For instance, anti-feminist Men’s Rights groups often cite the fact that men’s life expectancy is lower than women’s as a symptom of larger forms of structural victimization that uniquely harm men.[30] Others focus on educational gaps between boys and girls, citing boys’ under-achievement as indicative of some gendered apathy accompanying the cultural “crisis” that makes them feel out of place and without direction.[31] Some cite men’s un- and under-employment as indicators of how the crisis places them “on the sidelines” of social, cultural, and economic life,[32] and still others point to suicide rates among boys and men.[33]

The discursive sleight of hand common to all these arguments is that they present period effect data but make cohort effect claims.

Demographically, period effects refer to effects caused by events that affect many people at a particular time (e.g., the surge in death rates, particularly among the elderly, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2022). Conversely, cohort effects refer to generational effects that carry forward as people age (e.g., the higher death rates recorded by people born during the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic throughout their lives when compared with people born just prior to or after the epidemic). It is possible, demographically anyway, for something to have both period and cohort effects. But it is not possible to argue that something is evidence of a cohort effect without looking at longitudinal data.

Here is where the logic of the (white) “masculinity crisis” discourse tends to unravel. Evidence of various gender gaps is frequently given in snapshots, and we are not presented with the history required to document the claimed generational effects. The order of time is critical here—the indicators must be shown to follow the structural transformations that initially lead to the “crisis.” However, for each of the commonly cited indicators of the “crisis of masculinity,” the data provided often documents long-standing findings for boys and men, and some of the commentary even casually presents indicators as both cause and effect. As Morgan aptly states, “If these ‘symptoms’ represent a crisis, it is a crisis of long duration.”[34]

It is easier, in fact, to demonstrate that boys and men are victimized by cultural constructions of masculinity themselves. Indeed, a great many “indicators” of the alleged crisis, when interrogated with in-depth qualitative research, have been shown to result from boys and men attempting to live up to hegemonic cultural ideals associated with masculinity. As a case in point, from the earliest stages of the recent pandemic, epidemiologists noted that while women and men were equally likely to contract the disease, it appeared to be much more fatal in men. But it was not something unique to male biology that put men’s lives at greater risk; rather, it was the fact that men are much more likely to engage in other health-compromising behaviors that give rise to higher comorbidity rates[35] and less likely to engage in protective behaviors advocated by public health officials.[36]

On the Consequences of Labeling (White) Masculinity as “in Crisis”

Discourses of “crisis” are inherently alarmist; the questions we must ask, then, are whether the alarmism is justified, and what its consequences are. We have already seen that the claim of (white) masculinity being “in crisis” rests on unjustified premises. Nonetheless, the claim has very real consequences. We will examine two of these below: first, the presentation of boys and men as “victims,” and second, the social and cultural distraction offered by this claim, a distraction that negatively affects our ability to see issues that actually merit crisis discourse.

Discourses of “Masculinity in Crisis” as a Cultural Appropriation of Victimization

Research on socially and culturally privileged groups has shown that it is not uncommon for them to find new ways of morally and historically managing the systems of power and inequality from which they collectively benefit. As Robinson puts it,

While it is true that “crisis” might signify a trembling of the edifice of white and male power, it is also true that there is much symbolic power to be reaped from occupying the social and discursive position of subject-in-crisis.[37]

Maly, Dalmage, and Michaels conducted an in-depth qualitative interview study with white Americans who grew up in racially desegregating neighborhoods of Chicago between 1960 and 1980. They were particularly interested in how white residents made sense of the change, and discovered that such residents routinely invoked color-blind discourses associated with nostalgia to implicitly situate themselves as victims of the change (and the newer Black residents as victimizers). The researchers argue that “racialized nostalgia narratives […] do the work of maintaining [racial] boundaries […] to a white advantage.”[38]

Similarly, a large body of scholarship has found cisgender, straight, white men increasingly engaging in forms of cultural cooptation that have the collective effect of obscuring their relationship with power and status at precisely the historical moment when their power and status has been made newly visible.[39] Indeed, Morgan suggests that the “focus on some aspects of the crisis in masculinity may reinforce patriarchal institutions through an over-emphasis on the theme of ‘men as victims.’”[40]

This is all the more interesting in light of the many studies showing that boys and men are often loath to accept the status of victim, even when they have been victimized. For instance, in her research on men who file for domestic violence protection orders against women partners, Durfee finds that men engage in a patterned set of discursive “techniques” that allow them to narrate victimization in ways consistent with hegemonic configurations of masculinity. This, Durfee argues, reflects a larger discourse of “victimized masculinity,” supported by anti-feminist groups, wherein “the man is not a powerless ‘victim’ in need of protection. Instead, he needs state intervention to control his partner’s behavior before he is forced to take action against her—action that could result in her being harmed.”[41] Similar discursive techniques are recorded by Åkerström, Burcar, and Wästerfors in their research on Swedish men who have been victims of assault or muggings,[42] and by numerous studies which have found men to often resist classifying themselves as “victims” of sexual violence.[43]

Despite the documented reticence on the part of individual men to occupy the status of “victim,” however, the discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” appears to claim that boys and men as a whole are victims. While this might seem like a contradiction at first glance, we would argue that it is consistent with what Durfee has called a discourse of “victimized masculinity.” Boys and men are claimed to be victims of structural transformations far beyond their immediate control, thereby absolving them from any individual victimization. At the same time, the terminology of victimization is avoided and replaced with talk of a “crisis.” However, even while they resist using the language of “victims,” claims that masculinity is “in crisis” are still, in effect, victimization narratives.

Discourses of “Masculinity in Crisis” as Cultural Distractions

Discourses of masculinity as “in crisis” also have the effect of causing neglect within fields of research related to critical studies on men and masculinities, and to large-scale global crises. Putting the “crisis of masculinity” in conversation with interdisciplinary work in crisis studies,[44] Hearn suggests that a focus on masculinity as “in crisis” is not only unwarranted, but actually works as a kind of cultural distraction from real crises as well as from the ways these crises are often entangled with masculinities.

As an example, gun violence in the U.S. is an oft-cited “crisis.” Research suggests, however, that this crisis is better understood as a diverse collection of problems, many of which are intimately intertwined with cultural constructions of (white) masculinity.[45] Men are more likely to own guns,[46] and white men in particular.[47] Further, white men in economic distress are much more likely to find comfort in guns as a means of reestablishing a lost sense of gendered power.[48] Men’s greater risk of dying by suicide is driven by white men’s suicidality and access to firearms in the U.S.[49] Finally, research has shown that mass shootings, which are more common in the U.S. than anywhere else, are related to the gendered meanings of firearms and gun violence in that country.[50] [51] In sum, boys and men being wrapped up in gun violence is not as much an indicator of masculinity “in crisis” as it is an implication of their investment in masculinities that cause them to harm themselves and others.

The climate crisis is another global crisis requiring urgent attention and action, and here, too, we find men’s investment in masculinity at work. A large body of scholarship documents that men are much less likely than women to embrace environmentally friendly behaviors and products.[52] For instance, in a series of seven experiments, Brough et al. have shown that environmentally conscious behaviors are seen as more “feminine” by both men and women, and that engaging in them is perceived to threaten men’s sense of themselves (or other men) as “masculine.”[53] Thus, men are both much more likely to work in industries with a disproportionately negative impact on the climate and much less likely to engage in environmentally conscious behaviors at the individual level. The climate crisis is not necessarily caused by investments in masculinity, but investments in masculinity have been shown to exacerbate it.

As these two examples illustrate, the claim that masculinity is “in crisis” not only backgrounds many large-scale, appropriately-labeled “crises,” but also obscures the entanglement of masculinity itself in these larger crises. We can only concur with Hearn, then, that the discourse of “masculinity in crisis” at times operates as a kind of cultural distraction.[54]

Discussion and Conclusion

Men as a group can indeed suffer collective consequences of external conditions. Claims about such consequences, however, must be based on accurate detail, and they can only be tied to specific understandings and experiences of masculinity through in-depth qualitative research. Historical context, particularly regarding how men and masculinities have changed over time, is necessary if larger claims about “crisis” are to be more than just provocative talk.

“I am convinced that men are in a crisis,” journalist Christine Emba declares in a Washington Post opinion essay that went viral in 2023. Summarizing the different ways in which the feminist movement effectively challenged and destabilized specific forms of men’s collective dominance, Emba goes on to argue that this has left men in an uncertain and lonely state, lacking male role models, friends, and, generally speaking, direction in their lives. These claims are all empirically documentable, and some have empirical support. But little in the way of such support is offered in Emba’s article itself.[55]

Emba brings up resurgent forms of misogyny and ties these to observations that men seem to struggle connecting with women, forming friendships, articulating long-term goals, and more. “It felt like a widespread identity crisis,” she writes, “as if they didn’t know how to be.” Sociologist Raewyn Connell famously referred to such a condition as “gender vertigo.”[56] As Emba presents it, however, gender vertigo is itself evidence of a “crisis of masculinity”—a larger phenomenon by which men are being collectively victimized in historically novel ways.

Connell’s work highlights that masculinities are multiple and shifting. In other words, certain transformations of masculinity may be positively felt by some while inducing gender vertigo in others. As a result, the gender vertigo Emba describes “men” as experiencing may be less common than she suggests. To take one example, research regarding men’s friendship shows that Black men,[57] working-class men,[58] and gay men[59] all experience intimate, close friendships. The men Emba sees as “in crisis” in terms of friendship, then, are most likely straight, middle-upper-class, white men.

While Emba acknowledges that contemporary anxieties surrounding masculinity are not historically unique, she argues that men are being uniquely victimized by the contemporary “crisis,” and that newly emergent right-wing gender extremists have capitalized on this moment to offer men a solution. “What critics miss,” she writes, “is that if there were nothing valid at the core of these constructs, they wouldn’t command this sort of popularity. People need codes for how to be human. And when those aren’t easily found, they’ll take whatever is offered, no matter what else is attached.”

Indeed, the rise and proliferation of antifeminism online is a pressing concern.[60] The discourse of masculinity as “in crisis” has gone digital, providing swathes of boys and men worldwide with a new language for making sense of gendered change and positioning themselves as “victims,” a language that is seeping into offline antifeminism communities as well.[61] But rather than concur with Elba that the situation is indicative of an actual “crisis of masculinity,” we would argue that the current phenomenon mostly highlights the effective way in which the discourse of the “crisis of masculinity” has been utilized over the past two centuries, and is still being utilized today, to shore up the very systems and behaviors that promote men’s power and control.

TRISTAN BRIDGES is Professor of Sociology and Faculty Affiliate of Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

IAN ANTHONY is a Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

tbridges@soc.ucsb.edu; ianwaller@ucsb.edu

dePICTions volume 4 (2024): Victimhood

[1] See, for instance, Kenneth Clatterbaugh, Contemporary Perspectives on Masculinity: Men, Women, and Politics in Modern Society, Boulder: Westview Press, 1990; Michael Messner, The Politics of Masculinities: Men in Movements, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997.

[2] Tim Carrigan, Raewyn Connell, and John Lee, “Toward a New Sociology of Masculinity,” Theory and Society 14.5 (1985): 551-604; Messner, The Politics of Masculinities.

[3] For instance, Michael Messner, “Forks in the road of men’s gender politics: Men’s rights vs feminist allies,” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 5.2 (2016): 6-20.

[4] For instance, Herb Goldberg, The Hazards of Being Male: Surviving the Myth of Masculine Privilege, New York: Nash Publishing, 1976.

[5] David Morgan, “The Crisis in Masculinity,” in Kathy Davs, Mary Evans, and Judith Lorber, eds., Handbook of Gender and Women’s Studies, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2006, 109-123; Jeff Hearn, “The place and potential of crisis/crises in critical studies on men and masculinities,” Global Discourse 12.3-4 (2022): 563-585.

[6] Bruce Feirstein, Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche: A Guidebook to All that is Truly Masculine, New York: Pocket Books, 1982.

[7] Morgan, “The Crisis in Masculinity.”

[8] Hearn, “The place and potential of crisis/crises in critical studies on men and masculinities.”

[9] Let us note that while not all work on the topic cites Morgan’s distinction, the change in preposition entails different kinds of meanings even without his theorization.

[10] Gail Bederman, Manliness & Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996; E. Anthony Rotundo, American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era, New York: Basic Books, 1993.

[11] George L. Mosse, The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity, New York: Oxford University Press. 1996, 78.

[12] Theodor Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford, The Authoritarian Personality, New York: Harper & Row, 1950. While The Authoritarian Personality lacks any serious gender analysis, it has since been argued to characterize a certain configuration of masculinity. See, for instance, James W. Messerschmidt and Tristan Bridges, “Trump and the Politics of Fluid Masculinities,” Democratic Socialists of America, 15 July 2017 [14 June 2024].

[13] Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies, 2 vols., Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987 (vol. 1) and 1989 (vol. 2).

[14] Barbara Ehrenreich, “Foreword” to Theweleit, Male Fantasies, vol. 1, ix-xviii, here xvi.

[15] Lynne Segal, Slow Motion: Changing Masculinities, Changing Men, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

[16] Sally Robinson, Marked Men: White Masculinity in Crisis, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. See also Fred Pfeil, White Guys: Studies in Postmodern Domination & Difference, London and New York: Verso, 1995; David Savran, Taking it Like a Man: White Masculinity, Masochism, and Contemporary American Culture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998; and K. Allison Hammer, Masculinity in Transition, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023.

[17] Robinson, Marked Men, 11.

[18] Hamilton Carroll, Affirmative Reaction: New Formations of White Masculinity, Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

[19] See also Hammer, Masculinity in Transition.

[20] Elahe Haschemi Yekani, The Privilege of Crisis: Narratives of Masculinities in Colonial and Postcolonial Literature, Photography, and Film, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

[21] Tristan Bridges and C.J. Pascoe, “Elasticity of Gender Hegemony: Why Hybrid Masculinities Fail to Undermine Gender and Sexual Inequality,” in James Messerschmidt, Patricia Yancey Martin, Michael Messner, and Raewyn Connell, eds., Gender Reckonings: New Social Theory and Research, New York: NYU Press, 2018, 254-274; Tristan Bridges, “The Costs of Exclusionary Practices in Masculinities Studies,” Men and Masculinities 21.1 (2019): 16-33.

[22] Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991; Manuel Castells, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Volume 2: Power of Identity, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1997; John MacInnes, The End of Masculinity, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1998.

[23] MacInnes, The End of Masculinity, 11.

[24] C.J. Pascoe and Tristan Bridges, Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Continuity, and Change, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

[25] Raewyn Connell, Masculinities, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, 84.

[26] Tim Edwards, Cultures of Masculinity, New York and London: Routledge, 2006, 24.

[27] Connell, Masculinities; Pascoe and Bridges, Exploring Masculinities.

[28] Morgan, “The Crisis in Masculinity.”

[29] Susan Falludi, Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, New York: HarperCollins, 1999, 40.

[30] Emily Carian, “‘No Seat at the Party’: Mobilizing White Masculinity in the Men’s Rights Movement,” Sociological Focus 55.1 (2022): 27–47; Emily Carian, Good Guys, Bad Guys: The Perils of Men’s Gender Activism, New York: New York University Press, 2024.

[31] For instance, Christina Hoff Sommers, The War Against the Boys: How Misguided Feminism is Harming our Young Men, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000; Richard Reeves, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It, Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2022.

[32] For instance, Falludi, Stiffed; Andrew L. Yarrow, Man Out: Men on the Sidelines of American Life, Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018.

[33] Meta-analyses of gender gaps in suicide show that the matter is more complicated than often presented. For instance, Miranda-Mendizabal et al. discovered in a meta-analysis of 67 studies that boys and men die by suicide at significantly higher rates than girls and women. But they also found that girls and women were significantly more likely to be at risk of suicide attempts. That is, girls and women attempt suicide more frequently than boys and men while boys and men die by suicide more frequently than girls and women. And here, too, gender is the explanatory factor, as boys and men are simply much more likely to rely on more fatal methods of suicide. See Andrea Miranda-Mendizabal et al., “Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies,” International Journal of Public Health 64.2 (2019): 265-283.

[34] Morgan, “The Crisis in Masculinity,” 113.

[35] Tristan Bridges, Kristen Barber, Joseph D. Nelson, and Anna Chatillon, “Masculinity and COVID-19: Symposium Introduction,” Men and Masculinities 24.1 (2021): 163-167.

[36] Valerio Capraro and Hélène Barcelo, “The Effect of Messaging and Gender on Intentions to Wear a Face Covering to Slow down COVID-19 Transmission,” PsyArXiv 2020 [14 June 2024]; Janani Umamaheswar and Catherine Tan, “‘Dad, Wash Your Hands’: Gender, Care Work, and Attitudes toward Risk during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Socius 6 (2020): 1–14; Dan Cassino and Yasemin Besen-Cassino, “Of Masks and Men? Gender, Sex, and Protective Measures during COVID-19,” Politics & Gender 16.4 (2020): 1052–1062; James R. Mahalik, Michael Di Bianca, and Michael P. Harris, “Men’s attitudes toward mask-wearing during COVID-19: Understanding the complexities of mask-ulinity,” Journal of Health Psychology 27.5 (2022): 1187-1204; Carl L. Palmer and Rolfe D. Peterson, “Toxic Mask-Ulinity: The Link between Masculine Toughness and Affective Reactions to Mask Wearing in the COVID-19 Era,” Politics & Gender 16.4 (2020): 1044-1051; Katarzyna Wojnicka, “What’s masculinity got to do with it? The COVID-19 pandemic, men and care,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 29.1S (2022): 27S-42S.

[37] Robinson, Marked Men, 9.

[38] Michael Maly, Heather Dalmage, and Nancy Michaels, “The End of an Idyllic World: Nostalgia Narratives, Race, and the Construction of White Powerlessness,” Critical Sociology 39.5 (2018): 757-779, here 774.

[39] For instance, Demetrakis Z. Demetriou, “Connell’s Concept of Hegemonic Masculinity: A Critique,” Theory and Society 30.3 (2001): 337–361; Tristan Bridges and C.J. Pascoe, “Hybrid Masculinities: New Directions in the Sociology of Men and Masculinities,” Sociology Compass 8/3 (2014): 246-258; Tristan Bridges, “Antifeminism, Profeminism, and the Myth of White Men’s Disadvantage,” Signs 46.3 (2021): 663-688.

[40] Morgan, “The Crisis in Masculinity,” 122.

[41] Alesha Durfee, “‘I’m not a Victim, She’s an Abuser’: Masculinity, Victimization, and Protection Orders,” Gender & Society 25.3 (2011): 316-334, here 329.

[42] Malin Åkerström, Veronika Burcar, and David Wästerfors, “Balancing Contradictory Identities—Performing Masculinity in Victim Narratives,” Sociological Perspectives 54.1 (2011): 103-124.

[43] For instance, Heather R. Hlavka, “Speaking of Stigma and the Silence of Shame: Young Men and Sexual Victimization,” Men and Masculinities 20.4 (2017): 482-505; Doug Meyer, “Racializing Emasculation: An Intersectional Analysis of Queer Men’s Evaluations of Sexual Assault,” Social Problems 69.1 (2022): 39–57.

[44] Hearn, “The place and potential of crisis/crises in critical studies on men and masculinities.”

[45] For instance, Jennifer Carlson, Citizen-Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015; Angela Stroud, “Good Guys with Guns: Hegemonic Masculinity and Concealed Handguns,” Gender & Society 26.2 (2012): 216–238.

[46] Tara D. Warner, Tara Leigh Tober, Tristan Bridges, and David F. Warner, “To Provide or Protect? Masculinity, Economic Insecurity, and Protective Gun Ownership in the U.S,” Sociological Perspectives 65.1 (2022): 97-118.

[47] Katherine Schaeffer, “Key Facts about Americans and Guns,” Pew Research Center Short Reads, 13 September 2023 [7 June 2024].

[48] F. Carson Mencken and Paul Froese, “Gun Culture in Action,” Social Problems 66.1 (2019): 3-27.

[49] Jonathan M. Metzl, Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland, New York: Basic Books, 2019.

[50] Tristan Bridges and Tara Leigh Tober, Mass Shootings and Masculinity: Report for the Mass Casualty Commission, Nova Scotia Mass Casualty Report, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Mass Casualty Commission, 2022 [14 June 2024]; Tristan Bridges, Tara Leigh Tober, and Melanie Brazzell, “Mass Shootings and American Masculinity,” in Eric Madfis and Adam Lankford, eds., All-American Massacre: The Tragic Role of American Culture and Society in Mass Shootings, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2023, 19-32.

[51] For the gendered meaning of guns and gun culture in U.S. society, see also David Yamane, “The Sociology of U.S. Gun Culture,” Sociology Compass 11 (2017): 1–10.

[52] For instance, Joane Nagle and Trevor S. Lies, “Re-gendering Climate Change: Men and Masculinity in Climate Research, Policy, and Practice,” Frontiers in Climate 4 (2022): 856869.

[53] Aaron R. Brough, James E. B. Wilkie, Jingjing Ma, Mathew S. Isaac, and David Gal, “Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption,” Journal of Consumer Research 43.4 (2016): 567–582.

[54] Hearn, “The place and potential of crisis/crises in critical studies on men and masculinities.”

[55] Christine Emba, “Men are Lost. Here’s a map out of the wilderness,” The Washington Post, 10 July 2023 [14 June 2014].

[56] Connell, Masculinities.

[57] For instance, Brandon A. Jackson, “Bonds of Brotherhood: Emotional and Social Support among College Black Men,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 642 (2012): 61–71.

[58] For instance, Michèlle Lamont, The Dignity of Working Men: Morality and the Boundaries of Race Class, and Immigration, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

[59] For instance, Peter M. Nardi, Gay Men’s Friendships: Invincible Communities, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999; Anthony Christian Ocampo, Brown and Gay in LA: The Lives of Immigrant Sons, New York: New York University Press, 2022.

[60] For instance, Debbie Ging, “Alphas, Betas, and Incels: Theorizing the Masculinities of the Manosphere,” Men and Masculinities 22.4 (2019): 638-657.

[61] Carian, “‘No Seat at the Party.’”

Responses