Victimhood, Isēgoria, and Parrēsia

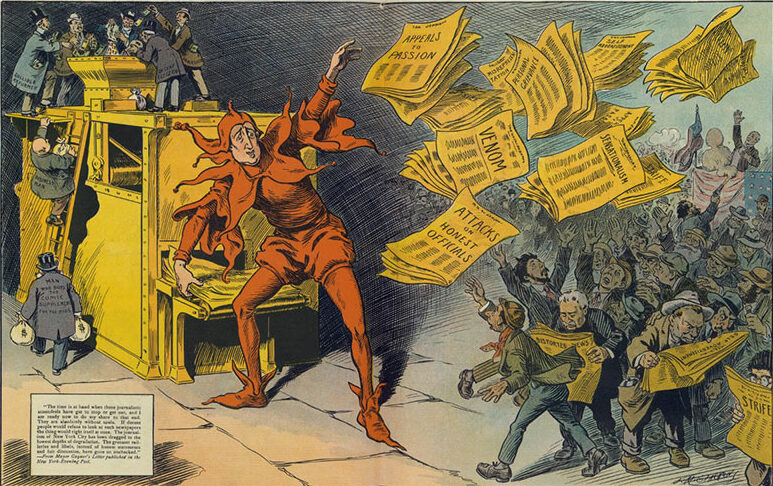

Image: “The Yellow Press” by L. M. Glackens (1910)

Victimhood, Isēgoria, and Parrēsia: Michel Foucault and US Conservatives

Andrea Di Carlo

Isēgoria (freedom of speech) and parrēsia (the obligation to speak the truth for the common good) are two concepts that are often conflated in contemporary political discourse. Whilst all US citizens are entitled to isēgoria (freedom of speech), it emboldens wealthy, male, white, and conservative politicians to say whatever they want, making implicit reference to parrēsia by claiming they are victims of a societal landscape where traditional American values are supplanted by the threat of secularism and a more varied population. By using Foucault’s two last lecture courses, The Government of Self and Other and The Courage of Truth, I will shed light on this conflation of concepts, showing how the Foucauldian toolkit can illuminate contemporary political debates and how minorities can mobilise parrēsia to call attention to inequalities.

Victimhood: A Taxonomy

Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning call victimhood “a kind of moral status, based on suffering and neediness.”[1] By casting themselves as victims, rich white people in the USA have applied this combination of suffering and neediness to themselves. In Mike King’s words, such people see themselves as

a racialised group—a group that is systematically discriminated against because of their race. They point to (often imaginary) affirmative action or welfare programmes, political correctness, and successful individuals of colour (of whom Obama is a figurehead) to posit an economic, political and cultural system that gives unfair advantage to people of colour.[2]

Especially since the election of Barack Obama, these supposed victims feel unseated from their position of privilege and threatened by a more diverse socio-economic landscape. They perceice any threat to the status quo as a threat to their own life. Two main features characterise their discourse: (1) The USA is no longer the country they grew up in. More importantly, it is no longer a predominantly Christian country and has become increasingly secularised. (2) This situation needs redressing and they are ready to voice their opinions. But how free can their speech be? And how can we critique their deployment of their freedom of expression? In order to address these questions, I will turn to Michel Foucault’s last lecture courses at the Collège de France, The Government of Self and Others (1982-1983) and The Courage of Truth (1983-1984), focusing on the notions of isēgoria and parrēsia.

Isēgoria and Parrēsia in Foucault

While both isēgoria and parrēsia are usually translated as “freedom of speech,” there are important differences in the ways such freedom comes into play. In The Government of Self and Others, Foucault invokes a “problem of speech,”[3] introducing the two different, albeit related, terms. On Foucault’s account, isēgoria amounts to

equality of speech, that is to say, the possibility for any individual, provided, of course, that he is part of the dēmos, to have access to speech […]; and finally isēgoria is the right to speak, to give one’s opinion in a discussion or a debate.[4]

Simply defined, isēgoria is the constitutional right to freedom of speech. From a legal point of view, the First Amendment of the US Constitution protects (virtually) any kind of speech. Everybody is therefore entitled to isēgoria, as unpleasant as it might be.

Foucault dwells upon another important concept of free speech, namely parrēsia, which means “free-spokenness,”[5] but is, in fact, radically different from isēgoria. In The Courage of Truth, the philosopher claims that parrēsia, this bold act of truth-telling, consists “in risking one’s life by telling the truth, risking one’s life in order to tell the truth, and risking one’s life because one has told the truth.”[6]

This telling the truth is, for the Foucault, “a political notion.”[7] This is usually the case because such discourses are very likely to be located in the political arena. Any act of parrēsia is vital to democracy, as it “consists in telling the truth without concealment, reserve, empty manner of speech, or rhetorical ornament which might encode or hide it.”[8] This discourse “will enable democracy to exist, and to continue to exist. True discourse must have its place for democracy actually to be able to take its course and be maintained through misadventures, events, jousts, and wars. So democracy can continue to exist only through true discourse.”[9]

Parrēsia involves isēgoria, then, but its scope is more specific. There is nothing lost in isēgoria, but parrēsia could harm the speaker. An act of parrēsia involves taking a chance because the ultimate purpose is to state unpleasant or problematic things. As Sergei Prozorov puts it, parrēsia is “only possible as an act of disobedience in the face of all social norms and conventions.”[10]

The framework of victimhood I have outlined above can only work in a democratic state where everybody can practise isēgoria. In what follows, to showcase how conservative white “victims” have conflated isēgoria and victimhood, I will discuss the role played by Tom Parker, the Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, in the recent controversy on the personhood of embryos, as well a wide range of statements by former President Donald Trump.

Challenges to the Establishment Clause: The Alabama Ruling and the Overturn of Roe v. Wade

The First Amendment is a cornerstone of US political life. Not only does this legal stipulation defend freedom of speech but it also prevents political assemblies from establishing an official religion. Specifically, the text reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”[11] In other words, a very rigorous separation between Church and State is critical to US democracy.

Over the years, Christian groups have gone to great lengths to attack the Establishment Clause, but the most controversial case occurred in Alabama, in February 2024, when the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos created through in vitro fertilization are children. In their ruling, the justices claim that unborn children “are ‘children’ […] without exception based on developmental stage.”[12] The court holds that embryos have a life of their own, which implies a Christian interpretation couched in legal terms.

From a Foucauldian point of view, this ruling invokes the freedom of speech warranted by isēgoria. However, there is more to this freedom of speech. Chief Justice Tom Parker’s concurring opinion is suffused with an unequivocable Christian idiom, referring, as it does, to Thomas Aquinas, the King James Bible, John Calvin, and William Blackstone. In short, Parker’s opinion is heavily reliant upon religious and theological arguments rather than a solid legal and jurisprudential underpinning. Whilst he is undoubtedly allowed freedom of speech, his religious views should not inform his legal philosophy.

Philip Gorski and Samuel Perry claim that responses such as Parker’s are triggered by demographic change. Things are fine as long as Christians are in power and keep societal change in check. With their privileged status being dramatically challenged, however, they are increasingly claiming victimhood and responding via reactionary methods.[13] It is here that Foucault’s problem of speech comes into play: Should Parker have written what he wrote? From the point of view of isēgoria, he is entitled to voice his opinion. However, despite the language of his concurrence, Parker is not practising any kind of parrēsia because, as a white Christian, he need not fear any consequence for his action.

The Alabama case is the outcome of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), the landmark Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade (1973). As is all too well known by now, the Supreme Court held that since there is no mention of abortion in the Constitution, terminating a pregnancy is not a constitutional right. In this regard, the comparison made between Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Roe v. Wade is troubling. The Court argued that:

Like the infamous decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, Roe was also egregiously wrong and on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided. Casey perpetuated its errors, calling both sides of the national controversy to resolve their debate, but in doing so, Casey necessarily declared a winning side. Those on the losing side—those who sought to advance the State’s interest in fetal life—could no longer seek to persuade their elected representatives to adopt policies consistent with their views. The Court short-circuited the democratic process by closing it to the large number of Americans who disagreed with Roe.[14]

The very questionable comparison between Plessy v. Ferguson, which introduced the infamous doctrine of “separate but equal,” applied until desegregation in the 1950s, and Roe is symptomatic of the way a conservative judiciary feels threatened by a challenge to the status quo. Another evidence of this perceived threat is the opinion of Justice Samuel Alito. Alito claims that

Roe’s defenders characterize the abortion right as similar to the rights recognized in past decisions involving matters such as intimate sexual relations, contraception, and marriage, but abortion is fundamentally different, as both Roe and Casey acknowledged, because it destroys what those decisions called “fetal life” and what the law now before us describes as an “unborn human being” […]. Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division.[15]

The last element to note in Alito’s opinion concerns his references. Like Parker, with his references to medieval and early modern theology, Alito refers to Sir Matthew Hale and Sir Edward Coke, who both claimed, in the seventeenth century, that abortion was “murder” and “a great crime.”[16] There is no mention of more recent legal authorities. Parker’s and Alito’s reference to medieval or early modern sources amounts to an acknowledgement that the world is no longer the one they grew up in and mores have significantly changed. As neither justice feels at home in today’s world, they voice the victimhood of privileged, white people slowly losing their standing in society.

The two rulings, then, are the products of a Christian and conservative victimhood discourse and, as such, significantly undermine the Establishment Clause because of their pronounced Christian bias. Elizabeth A. Castelli delves more deeply into this victimhood discourse, characterizing it as

a broader and growing trend in political discourse as it emerges from certain branches of right-wing political Christianity. This trend mobilizes the language of religious persecution to shut down political debate and critique by characterizing any position not in alignment with this politicized version of Christianity as an example of antireligious bigotry and persecution. Moreover, it routinely deploys the archetypal figure of the martyr as a source of unquestioned religious and political authority.[17]

Ruth Braunstein has reinforced Castelli’s argument by claiming that what is at stake for certain Christians here is the perceived lack of “religious freedom.”[18] This ostensible lack of religious freedom, then, is what justifies these justices’ efforts to undermine one of the central tenets of the US Constitution, the separation of Church and State. Clearly, both justices feel that the First Amendment should protect what they write or say; however, theirs is just an iteration of isēgoria, not of parrēsia. Their social status insulates them from any consequences, and therefore, their discourse of victimhood does not hold.

The Perceived Victim-in-Chief: Donald Trump

Donald Trump embodies a different type of victimhood than Parker and Alito. He is not concerned with religion (even though his Supreme Court appointees have solid conservative credentials and overturned Roe v. Wade). Rather, he embodies the victimhood of the rich, white man threatened by the rule of law. Elizaveta Gaufman and Bharath Ganesh note that while Trump “as a white, straight male can hardly be seen as a marginalized voice, he nevertheless managed to galvanize a substantial amount of support among the American population by marketing himself as an anti-establishment figure.”[19]

Clearly, Trump’s policies are not the product of an anti-establishment figure; it would be more correct to assert that the New York entrepreneur was supposed to re-establish the “racial contract,” a social contract where white people are in charge and Black people are subpersons who have to obey the white ruling class.[20] The Obama era had turned the stipulations of the contract on its head, and Trump was tasked to heal the resluting trauma of white victimhood. In Donald E. Pease’s words, his actions cater to “the fantasy in which only the restoration of power of white supervisory control of black lives can contain the trauma of its Real—the spectacle of a black man in charge of a nation.”[21]

Trump’s rhetorical victimhood contains a feature deeply rooted in the American psyche: the apocalyptic tropes of Puritanism, especially the Puritan jeremiad, a rhetorical technique constituted by a cycle of “promise, decline, and redemption.”[22] One of the most prominent scholars of Puritanism, Sacvan Bercovitch, claims that “the emphasis on figural providence has a single purpose: to impose a sacred telos upon secular events.”[23] Through what Wendy Brown calls his “apocalyptic populism,”[24] Trump casts himself as such a providential figure. In his own words, he is “your warrior,” “your justice,” “your retribution,”[25] a new millenarian prophet who stands for redemption in the face of victimization, isolation, lack of opportunities, and a sense of despair.

Aligning with the promise of redemption is a claim to martyrdom. It is not surprising that Trump frequently claims that his trials are a witch hunt (the Salem witch trials and their victims being another important staple of the American psyche and one of its most important rhetorical tropes).[26] As a martyr, a victim of the establishment, this new witch invokes a sense of respect and demands to be heard. In Foucauldian terms, though, once again, Trump is closer to isēgoria than parrēsia, as he seems to risk little by way of consequences in his controversial and violent statements, which include horrific sexist claims (“grab them by the pussy”)[27] and direct threats (“I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters, OK?”).[28]

This aggressive response, in fact, is perhaps the main point of Trump’s rhetoric of victimhood in that the latter helps to legitimise the former. As Wendy Brown puts it, Trump mobilises “not simply class resentment but white rancor, especially white male rancor, about lost pride of place (social, economic, cultural, and political) in the context of four decades of neoliberalism and globalization.”[29] What he offers his followers, in Casey Ryan Kelly’s words, is

an emotional-moral framework in which feelings and affects such as anger, rage, malice, and revenge are never at rest and no one act of vengeance can dissipate the nation’s desire for more. The message sustains an affective charge by addressing intractable enemies with vague and ill-conceived objectives.[30]

Trump’s rhetoric inspires thymos. According to Peter Sloterdijk, thymos is the “manly courage […], without which it is impossible for the practitioner of urban life to assert himself.” In the framework of thymos, rage is “ allowed to live a second life as useful and ‘just rage,’ responsible for protecting its possessors against insults and unwanted impositions.”[31] Thymos, then,is the rage and discontent felt by the people who believe that Trump is their latest beacon and last hope.

By casting himself as the victim, the very embodiment of conservative victimhood, Trump allows his voters to confront the grievances of everyday life. However, he galvanises his voters not by providing real solutions, but by using his own ostensible victimhood to double down on their resentment towards the establishment.[32] Far from practising parrēsia, he offers nothing bar his isēgoria, provoking a wide range of aggressive and rancorous responses that substitute for any real change in his voters’ life situations. His isēgoria simply calls on his followers, as Foucault puts it, to “give one’s opinion by voting for a decision or for the choice of leaders.”[33]

Parrēsia is for Marginalised Groups

There is no conservative victimhood, not least because, thanks to Trump’s judicial appointments, right-wing judges are attacking civil rights with impunity. There is no conservative victimhood because demands for fairness or equality cannot be equated to “woke indoctrination.” By using the ubiquitous word “woke,” self-proclaimed victims have managed to challenge the First Amendment and rewrite history.[34] Ennobled by “their own suffering,”[35] as Kelly puts it, they are now, in fact, successfully governing.

Hope is not lost, however. Parrēsia has been fruitfully used by progressive groups both past and present. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party and civil rights activists took real risks for change. Today, the Black Lives Matter movement and climate justice groups offer a strong and brave response to inequalities. Parrēsia is the most powerful weapon at such groups’ disposal to denounce racism, structural inequalities, or demagoguery.

Acts of parrēsia, as Corey McCall contends, “challenge injustices […] committed by the strong on behalf of those who are not powerful enough to contest the ruler by force.”[36] As Foucault argues, parrēsia is “a truth-telling, an irruptive truth-telling which creates a fracture and opens up the risk: a possibility, a field of dangers, or at any rate, an undefined eventuality.”[37] Our commitment to telling the truth in the face of a reactionary victimhood discourse is the best way to resist attacks on human rights and to fight for equality and social justice.

ANDREA DI CARLO holds a Ph.D. in the History of Philosophy from University College Cork, where he has taught philosophy for first-year students and political philosophy. He previously studied Philosophy, English Literature, and Old English Studies at the University of Pisa. His main areas of interest are Foucault, existentialism, and early modern philosophy (Machiavelli and Montaigne). Along with his co-author, Dr. Miranda Corcoran, Lecturer in Twenty-First Century Literature at University College Cork, he has published in Reformation, History of European Ideas, eSharp, Arrêt sur Scène, and with Palgrave.

dePICTions volume 4 (2024): Victimhood

[1] Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning, The Rise of Victimhood Culture. Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 22-23.

[2] Mike King, “The ‘knockout game’: moral panics and the politics of white victimhood,” Race & Class 56.4 (2015): 85-94, here 88-89.

[3] Michel Foucault, The Government of Self and Others. Lectures at the Collège de France (1982-1983), edited by Frédéric Gros, translated by Graham Burchell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 151.

[4] Foucault, The Government of Self and Others, 150-151, emphasis added.

[5] See Foucault, The Government of Self and Others, 43.

[6] Michel Foucault, The Courage of Truth (The Government of Self and Others II). Lectures at the Collège de France (1983-1984), edited by Frédéric Gros, translated by Graham Burchell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 234, emphasis added.

[7] Foucault, The Courage of Truth, 8

[8] Foucault, The Courage of Truth, 10.

[9] Foucault, The Government of Self and Others, 184.

[10] Sergei Prozorov, Biopolitics after Truth, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021, 148, emphasis in the original.

[11] National Constitution Center, “First Amendment: Freedom of Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, and Petition” [9 June 2024].

[12] Supreme Court of Alabama, October Term, 2023-2024, 16 February 2024, 30-31, 34 [9 June 2024].

[13] Philip L. Gorski and Samuel L. Parry, The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022, 8.

[14] Supreme Court of the United States, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U. S. 1, 5 (2022) [16 March 2024].

[15] Supreme Court of the United States, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U. S. 1, 5-6 (2022) [16 March 2024].

[16] Supreme Court of the United States, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U. S. 1, 17 (2022) [16 March 2024].

[17] Elizabeth A. Castelli, “Persecution Complexes: Identity Politics and the ‘War on Christians,’” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18.3 (2007): 152-180, here 154.

[18] Ruth Braunstein, “Embattled and Radicalizing: How Perceived Repression Shapes White Evangelicalism,” in Anand Sokhey and Paul Djupe, eds., Trump, White Evangelical Christians, and American Politics: Change and Continuity, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024, 131-161, here 133.

[19] Elizaveta Gaufman and Bharath Ganesh, The Trump Carnival: Populism, Transgression and the Far Right, Boston: de Gruyter, 2024, 2.

[20] On the racial contract, see Charles W. Mills, The Racial Contract, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997, 11.

[21] Donald E. Pease, “Donald Trump’s Settler-Colonist State (Fantasy): A New Era of Illiberal Hegemony?,” in Liam Kenney, ed., Trump’s America: Political Culture and National Identity, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020, 23-53, here 36.

[22] Wm. Bryan Paul, Joel Lansing Reed, and Josh C. Bramlett, “Mr. Flake Gets Out of Washington: The Jeremiadic Martyrdom of Jeff Flake,” Western Journal of Communication 88.1 (2024): 240-258, here 246.

[23] Sacvan Bercovitch, The Puritan Origins of the American Self, with a new preface, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011 [1975], 52.

[24] Quoted in Daniel Nilsson DeHanas, “The spirit of populism: sacred, charismatic, redemptive, and apocalyptic dimensions,” Democratization (2023), 1-21, here 10.

[25] Aaron Blake, “Trump’s dark ‘I am your retribution’ pledge,” The Washington Post, 6 March 2023 [18 March 2024].

[26] Ankush Khardori, “Trump Seems to Be the Victim of a Which Hunt. So What?” Politico, 30 March 2023 [18 March 2024]. For a thorough and detailed assessment of the Salem witch trials, see Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, New York: Vintage Books, 2002.

[27] Libby Nelson, “‘Grab ’em by the pussy’: how Trump talked about women in private is horrifying,” Vox, 7 October 2016 [11 December 2023].

[28] Reuters, “Donald Trump: I could shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters,” The Guardian, 24 January 2016 [11 December 2023].

[29] Wendy Brown, “Neoliberalism’s Frankenstein: Authoritarian Freedom in Twenty-First Century ‘Democracies,’” Critical Times 1.1 (2018): 60-79, here 60.

[30] Casey Ryan Kelly, “Donald J. Trump and the rhetoric of ressentiment,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 16.1 (2020): 2-24, here 3.

[31] Peter Sloterdijk, Rage and Time: A Psychopolitical Investigation, translated by Mario Wenning, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010, 12, emphasis added.

[32] Sjoerd van Tuinen, The Dialectic of Ressentiment: Pedagogy of a Concept, London: Routledge, 2024, 25.

[33] Foucault, The Government of Self and Others, 150-151, emphasis added.

[34] In this context, Florida governor Ron DeSantis has been one of the most active culture warriors. For more on DeSantis and his educational policies, see Gary G DeSantis, “We believe in education, not indoctrination: Governor Ron DeSantis, critical race theory, and anti-intellectualism in Florida,” Policy Futures in Education 22.5 (2024): 1-16.

[35] Ryan Kelly, “Donald J. Trump and the rhetoric of ressentiment,” 19.

[36] Corey McCall, “Parrēsia,” in Leonard Lawlor and John Nale, eds., The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014, 334-336, here 335.

[37] Foucault, The Government of Self and Others, 63.

Responses