Sustainable Classics: Angelin Preljocaj’s Swan Lake Devant la Nature

Sustainable Classics: Angelin Preljocaj’s Swan Lake Devant la Nature

by Tatiana Senkevitch (Paris, France)

THERE is scarcely a more iconic ballet than Swan Lake. Its main heroine—a lanky, supple creature in a white tutu whose languishing face is crowned by a headpiece made of feathers—is the very emblem of a ballerina. Hovering in her statuesque arabesque, she is the Mona Lisa of ballet history. One of the most “classical” in classical ballet (this repetition is generated by the history of this form of dance), Swan Lake never loses its appeal for restaging, remakes, and emulations for generations of new artists and audiences. In 2020, Angelin Preljocaj, the French choreographer whose works are already ranked as contemporary classics, created his own distinctive version of Swan Lake for his Aix-en-Provence-based company, the Preljocaj Ballet. Delayed for almost a year because of the pandemic, the ballet was finally released in the summer of 2021 and performed in November at the festival Diaghilev P.S. in St Petersburg, Russia. The new version calls particular attention to the permanent value of nature encoded in the familiar title of the ballet: before there is any story of a swan, there is a lake.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

Swan Lake narrates a timeless story of love, betrayal, seduction, and remorse as powerfully expressed by Petr Tchaikovsky’s score. The first staging of the ballet in 1877 by the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, achieved by the choreographer Julius Reisinger, held little promise of a long stage life for Tchaikovsky’s music, and Swan Lake’s ascent to its status among the untarnished classics only began in 1895, at the Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg. Marius Petipa, in collaboration with Lev Ivanov, found fresh choreographic and theatrical means for the libretto based on a mélange of Gothic legends. Petipa accentuated the leitmotif of tragic doom and developed it through a captivating stage action. Following his talent for a dramaturgically potent dancing tableau, he explored the changes between the well-lit, coloristic feasts at the court and the nocturnal lake scenes presented in a bluish light suitable for the metamorphosis of swans into women.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

The 1895 version united the visions of two choreographers. Petipa composed the first act and the lion’s share of the third act, those parts that developed in the court setting, while charging Lev Ivanov, his assistant at the time, with composing the dances of the second and fourth acts, those presenting the lake scenes. Ivanov’s choreographic acumen thrived on the lyrical scenes, expressing the mystery of nature at night. Thus was created the image of the ballerina-swan that would be refined throughout the centuries to come.

In the 1895 production, the difference between the two principal female characters—Odette, the queen of the enchanted swans, and Odile, the sorcerer’s daughter who seduces the naïve prince during the court ceremony—became determined choreographically. The supple, continuously fluid movements of Odette and the fiery steps of Odile enriched the action. In the subsequent libretti (each new production made subtle changes to the original plot), Odile’s role metamorphosed from the sorcerer’s daughter into the Black Swan, a negative double of Odette. The tradition of one ballerina performing both roles brought an additional thrill for the public and an increased difficulty for performers. The versatile technique and captivating artistry required from the ballerina, along with the precision and elegance of lines for the corps de ballet, made Swan Lake a testing ground for dancers. The technical prowess of the great Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani, who danced the double role of Odette-Odile in 1895, established the highest standards for future performers in this role.

The 1895 version of Swan Lake remained a singular production of the Russian Imperial Theatres for decades. Later, regardless of Swan Lake’s origins in the Petipa epoch, Soviet theatre appropriated the authority of the original. Through consistent revivals by Soviet choreographers, the ballet became a cherished œuvre of national culture, commodified by the Soviet state for purposes of cultural diplomacy. In the West, Swan Lake was known mostly in abbreviated versions until the 1930s. It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that leading companies outside Russia began mounting their full versions of the ballet, often with the assistance of Russian dancers and ballet-masters dispersed in Europe after the 1917 Revolution.

Gradually, Swan Lake assumed a key position in the repertoire of many dance companies. Certain productions of the ballet deviated from or even subverted its original plot, historical context, and classical vocabulary of forms. This process, normal for the afterlife of a classical work of art, exists now in parallel with the tendency to restore the ballet’s “true,” antique choreography based on archival research and the historical record. Although classical dance in Petipa’s tradition belonged fully to the cultural context of Russian monarchy, his balletic theatre expressed a certain theatrical form resonating with contemporary choreographers and their own cultural contingencies. Swan Lake’s lyrical pathos with its ideologically laced mythology of white swans yields to a manifold conceptual and interpretive framework. In many ways, Swan Lake has proved its organic sustainability for contemporary art.

One may ask, then, why Angelin Preljocaj, a choreographer who has bridged the traditional and the innovative through the universal language of dance, has waited until now to present a version of Swan Lake. Having studied both classical and contemporary technique, Preljocaj leans firmly towards the latter, yet always expresses his admiration for the former, and not only rhetorically: in 2018, the year of Petipa’s bicentennial, Preljocaj composed the short ballet “Ghost” as his homage to the choreographer’s enduring contribution to dance. Throughout his diverse career, Preljocaj has experimented with extreme emotional states and investigated the motivations of his characters, expressing them through the corporeal codes of contemporary dance. Yet, he has always striven to tell, or retell, familiar stories by purely visual means. Like Marius Petipa, Preljocaj believes in the unlimited potential of the theatre of dance. He seeks his inspiration in a wide range of sources, such as world literature, mythology, ethnography, and the Bible.

Consequently, Preljocaj’s approach to the canonical story of Swan Lake is neither iconoclastic nor passively emulative—it is more akin to a cinematographic remake in which the leading characters of the canonical version are placed in a different context. The juxtaposition between the real and mystical worlds in the traditional Swan Lake acquires the contours of current urban life that clashes with nature. The latter is represented by a nocturnal lake, the swans’ habitat. In Preljocaj’s theatre, the swans are no longer enchanted maids but wild waterbirds. Furthermore, the royalty on both sides is abolished; Odette, the queen of swans, becomes nature’s spokesperson, a leader of her clan.

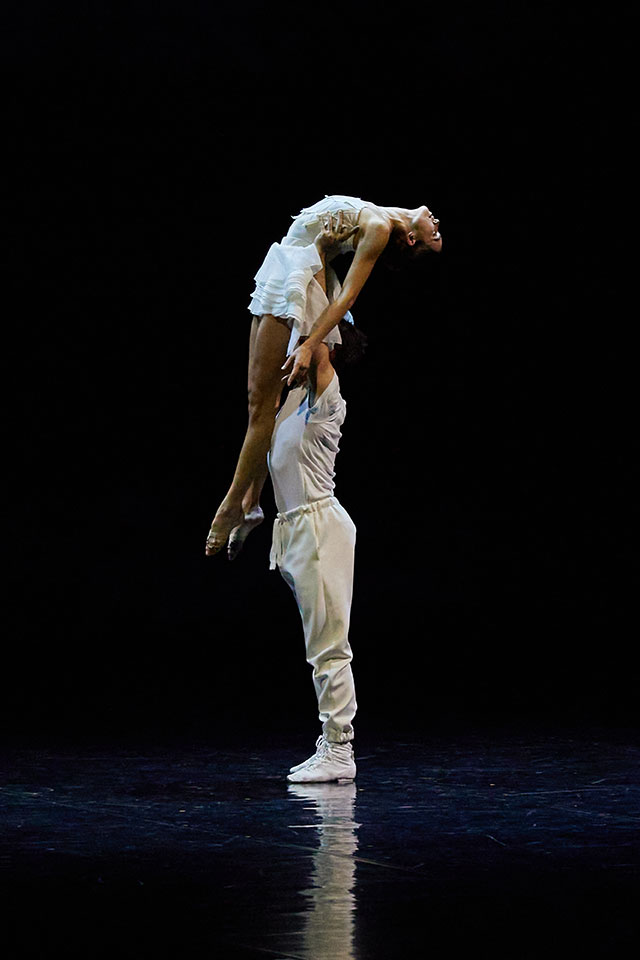

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Diaghilev P.S. Festival

Prince Siegfried is no heir to a patrician dynasty but son of a wealthy developer. Siegfried’s father, along with his business partner, cast in the likeness of von Rothbard, conceives the erection of a chemical plant (as it appears from the props) that will destroy the lake. Siegfried is a rebel and a loner. He escapes the party thrown by his parents to wander around the city’s outskirts. After being beaten to unconsciousness by a group of lake poachers (who would take a guy in an urban hoodie for a rich heir?), he is restored to life by a swan. Amazed and touched by the swan’s wild caresses, Siegfried promises to protect her and her she-mates. Although rendered as wild creatures, Preljocaj’s swans still embody ultimate femininity in their languishing, caressing moves. In the White Swan pas de deux, Preljocaj creates a powerful scenario for an (im)possible enchantment between a human and a swan. Preljocaj’s choreography transforms the familiar sostenuto movements and transitions invented by Lev Ivanov into a different mode of plasticity, calling attention to the vulnerability and gentleness shared by both characters, as if suggesting the state of mutual humility as an ideal mode of encounter between man and nature.

Evil lurks, however. At the corporate party, dramaturgically corresponding to the presentation of the brides in the third act of the classical Swan Lake, Siegfried is smitten by the daughter of his father’s business partner. This mysterious woman, clad in black, vaguely resembles the White Swan, but with a brusque and arrogant touch. Siegfried announces his engagement to the woman in black and thus breaks his promise to the White Swan. Having realized his error, he falls into despair, literally and otherwise. Consoled by his mother, he attempts to salvage the situation, coming to the lake to fight for his cause, but in vain. Odette dies in his arms, her mates are doomed, and, as the curtain falls, the lake turns into a menacing, oily puddle.

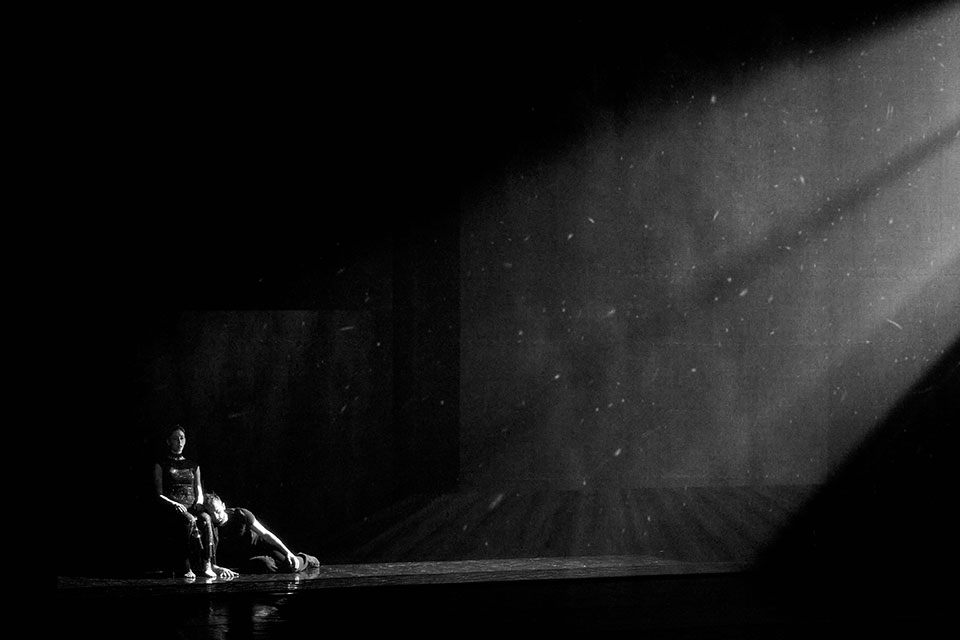

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Diaghilev P.S. Festival

The death of the White Swan, replacing the suicide of two lovers in the classical version, adds a touch of realism—even noir—to the tragic edge of Tchaikovsky’s music. This increasing tenebroso lyricism appears most notably in the choreographer’s recent Winterreise, set to Schubert’s cycle of songs for the poems of Wilhelm Müller. There, as in Swan Lake, love, hope, and nature are all succumbing to darkness. The evil force in Swan Lake, however, is not mystical or psychological, but concrete and identifiable. Its source lies in the corporate greed that neglects, mutilates, and destroys both humans and nature. Retelling Swan Lake as a story of a threatened natural site, a locus of beauty and purity, Preljocaj appeals to the public’s sympathy and compassion by pure theatrical means, trying to attune the dance with the zeitgeist of the moment. His dance theatre seems to tacitly absorb the politics of ecological concerns into a poetics that had come to seem rigidly classical.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

There are some novelties brought to the traditional plot as well. Preljocaj transforms the role of Siegfried’s mother from an emblem of power into an embodiment of motherly love and gentleness. A passive victim of the corporatist mentality, she stands on the side of her idealistic son. The duet between Siegfried and his mother in the narrow strip of the avant-scene evokes their loneliness in the prison of corporate norms. Notably, Preljocaj stages this duet to Tchaikovsky’s choral music that he found outside the traditional partition of Swan Lake. The maternal love strengthens Siegfried’s improbable fascination with the lake creature, as all three—the mother, the swan, and Siegfried—are victims of violence or at least emotional indifference in a pragmatic world.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Diaghilev P.S. Festival

Embarking on a remake of Swan Lake, any choreographer confronts the question of finding her/his own visual idiom for the movements of the dancers-swans. The swans’ pattern of pas and poses as invented by Ivanov remains powerful and enduring to the degree that changing it becomes a greater challenge than updating the time of the action. Preljocaj approaches this challenge by not fully negating the already existing visual idioms established by Petipa-Ivanov but by reinitiating them through his own prism of dancing forms. The orderly lines of the upright, statuesque figures of the classical swans-ballerinas become models for Preljocaj’s swans, whose bodies are equally subject to gravity and horizontality.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Diaghilev P.S. Festival

Preljocaj approaches the “court” gatherings and the swan scenes in distinctly different ways. The court gathering of the first act becomes a cocktail party at the corporate headquarters. This social milieu manifests itself through a relentless marching in lines, with the port de bras movements redolent of either the athletic parades of the Soviet era or the aerobic exercises of the sixties. The synchronicity and automatism of these steps, their deliberate anti-classicism, is mitigated by the floating melodies of Tchaikovsky’s waltz. The costume designer Igor Chapurin, who has already worked with Preljocaj on several projects, selects for the scene a bright, flashy palette of colors that makes the dancers look savvy and confident, much in the spirit of the “casual-smart” bobos. The scene ends with disco dancing, something that a modern royalty of financial affluence might well indulge in.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

In the third act, that of the ball at the castle in traditional versions, the color-filled atmosphere of the opening scenes is reduced to a black-silvery palette, corresponding to a black-tie evening. The dancers, arranged in a rectangular formation, sit on chairs as if viewers at a theatre. Here again, the robotic synchronicity of movements becomes menacingly heartless and perfunctory, thus setting the stage for the appearance of the Black Swan.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

One of the ballet’s fortuitous moments is Preljocaj’s reinterpretation of Petipa’s and Ivanov’s ethnic dances at the ball. The Spanish and Neapolitan dances are particularly pungent in their reconstruction of the “character” aspect through Tchaikovsky’s music, albeit without any costumes or special props being enlisted. The ethnic aspect succumbs here to a particular kind of a techno-pop universalism. Economic and efficient in his means, Preljocaj remakes the dances by means of two couples producing kaleidoscopic moves of staggering dynamism on the spot.

In contrast, the scenes at the lake are rendered with a vibrant plasticity encompassing the totality of the space. Working with a group of sixteen dancers, Preljocaj arranges them in pairs, circles, diagonals, and, most strikingly, into a v-shape formation. This v-formation of dancers with heads tilted backwards, enhanced by the light revealing the anatomy of their necks, becomes a visual motif for the ballet. The formation highlights the collective in the cause of the swans, their unanimous unity in the face of human intervention. At times, the choreographic arrangements of the swan scenes allude to the classical prototype, yet Preljocaj creates his own morphology of pas. He aligns the arabesques more horizontally than vertically, using the broken wrists of arms as pulsating extensions of swan’s necks. Tapping in a plié à la seconde recalls the steps of the waterbirds on the ground. The choreographer almost does away with the high-leg broken attitudes and flapping arms, as if underscoring that his swans stay close to the water, surface, and horizon. Preljocaj retouches the pas de quatre of the little swans—an instant crowd-pleaser—in accord with his visual aesthetics as well. Fortuitously, his visual language avoids the pitfalls of hybridization, a tricky middle ground between the “classical” and contemporary that often plagues the remakes.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

In the pas de deux of Odette and Siegfried, Preljocaj pulls his tour de force—a dancing dialogue infused with a sensuous poetics. His White pas de deux is no longer a monologue by Odette such as in the “classical” version, but an encounter of the two souls and bodies in space-time. For Preljocaj, Odette is a swan, a wild creature, establishing her contact with Siegfried through the twitching movement of her head around his chest and jarred steps. She is a princess of a different order, that of nature, and as such she does not need the accoutrement of a balletic princess—pointe shoes, shiny tutu, and a little crown on her head. Undoubtedly, she is a creature of absolute beauty, a beauty one encounters when enraptured by a sight of nature, one that comes always unadorned.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

Odile, in contrast, is a woman of power, a product of the corporate world, thoroughly human but with strange bird-like moves. The viewer ponders how Siegfried could mistake Odile for another creature. Or should he not be duped at all but fall for a woman instead of a waterbird? The so-called Black pas de deux corresponds to the letter of the classical version in its open seductiveness but loses the subtle poetics offered by the choreographer in the White pas de deux.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

The real violence appears in the final act. Unlike the tragic end of the traditional Swan Lake, the scene of captivity of the White Swan by three hunters demonstrates that the destructive evil resides in humans. Visually, the act of aggression becomes a humiliating un-swaddling of the dancer’s body. Flying ribbons of the swan’s costume create a tragic dance of the body’s extensions. One might remember here Preljocaj’s inventive use of the hair braids in his Fresque. The costumes of the swans, consisting of short, floating skirts and tight bodices with the light imprint of the thorax, result again from the flourishing collaboration between the choreographer and the fashion designer Igor Chapurin, who feels so keenly the meaning and function of the theatre costume. Not only do these costumes liberate the swans from rigid, white tutus; they also increase the dramatic effect of the swans’ animality and underscore a different aesthetic of their corps.

Le lac des cygnes, Ballet Preljocaj, photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

Preljocaj’s Swan Lake dazzles the public with moments of genuine dramatic intensity and the compelling rhythm of scenes even though the performance runs for two hours with no intervals. No booklet with texts or synopsis is necessary for the viewer: the visual narrative works impeccably, and the public instantly positions itself on the side of the good. The production is theatrical in the best sense of the word, not least because the choreographer garners an excellent team for it. Boris Labbé, responsible for the video backdrops, underlines the choreographer’s take on the narrative details. Igor Chapurin’s costumes sharpen the choreographic ideas. Light designer Éric Soyer conceives a gentle grisaille color scheme corresponding to both the urban and lakeside scenes. The recorded music, however, an inevitable factor in such productions, reduces the overall aesthetics of Preljocaj’s theatrical concept.

Artists of the Ballet Preljocaj after their performance at the Diaghilev P.S. Festival in St Petersburg, November 2021

By letting the white swans die from human intervention, Preljocaj subverts the atemporal opacity of the old tale. His Swan Lake remains a narrative ballet with its action bound to the concrete realities of today’s world, such as industrial encroachment, the stock exchange (featuring so prominently in one of the video backgrounds), and corporate retreats. So, what happens when the mysterious “once upon a time” becomes here and now, not then, particularly in the art of ballet? It has become almost habitual, for instance, to put characters from Handel or Verdi in contemporary military uniform without, however, changing the lines or the melodies they sing. Such perfunctory modernization of visual context, which can infuse an old libretto with new meaning, is not desirable in ballet, because the language of dance is essentially corporeal and as such necessitates the change of formal codes more profoundly.

Artists of the Ballet Preljocaj after their performance at the Diaghilev P.S. Festival in St Petersburg, November 2021

Swan Lake is not the first instance of Preljocaj’s interest in how older art blends with modern experiences and ideals, as he consciously takes the position not only of a choreographer (his main métier), but predominantly of a contemporary artist at large working at the threshold of art and society. It seems that he consciously aims at investigating the possibilities of different cultural practices and themes via codes of dance. On the one hand, he privileges the historical structure of ballet in which swans dance their story of captivity, although he departs from the classical vocabulary of forms. On the other hand, he changes the context by making it more recognizable, pertinent, and frankly political, as ecology becomes part and parcel of political and cultural concerns today. There is no real contradiction at this junction because Preljocaj keeps this conversion within the realm of theatrical contingency. At its best historical moments, classical theatre—French theatre at least—had no fear of engaging with politics, as did Racine or Hugo. The classical as a steady cultural platform not only inspires Preljocaj but also lends him its authority to refresh certain formal strictures and reconsider the malleability of tradition, or perhaps its generic potential for sustainability. Whether with or without tutus, swans and lakes should be protected.

Artists of the Ballet Preljocaj after their performance at the Diaghilev P.S. Festival in St Petersburg, November 2021

PICT and the author would like to express heartfelt thanks, for their assistance in the preparation of this essay, to Natalia Metelitsa, Director of the St Petersburg Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art and Artistic Director of the Diaghilev P.S. Festival; Frédérique Florent of Ballet Preljocaj; Alice Psaroudaki; Alexandra Starkman; Svetlana Shevelchinskaya; and Lucas Viallefond.

Responses