Ecoperformance: Depictions of Possible Futures for the Performing Arts

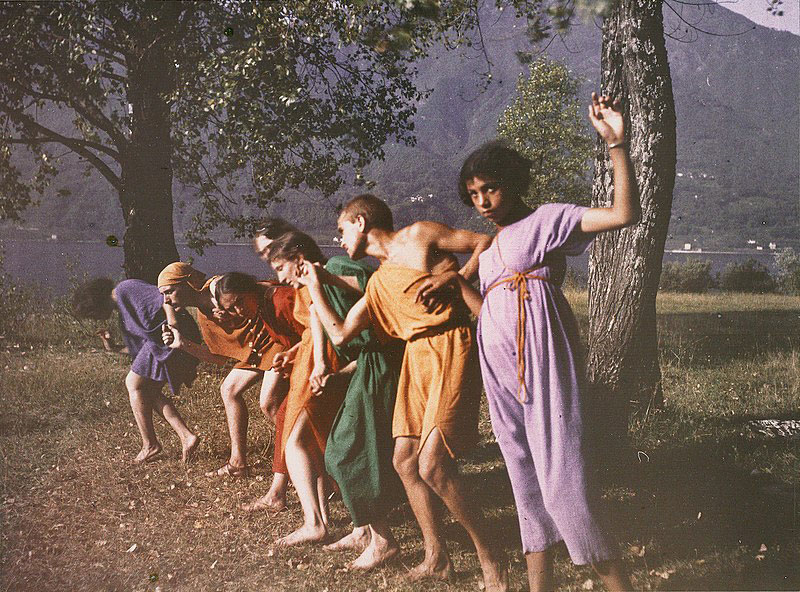

Photograph of Rudolf von Laban’s dance company on the shores of Lake Maggiore, near Ascona, in 1914

Wolfgang Pannek

Ecoperformance: Depictions of Possible Futures for the Performing Arts

The article introduces ecoperformance and ecorporeality, two concepts developed by Brazilian choreographer Maura Baiocchi and German director Wolfgang Pannek in the performing arts investigations of Taanteatro Companhia. With special reference to the International Ecoperformance Festival, the text discusses the overcoming of the dominant anthropocentric performing arts paradigm, that is, the departure from the Anthropo-Scene towards a Symbio-Scene. In this context, it explores how far Nietzsche’s perspectivism and Viveiros de Castro’s multi-perspectivism may prove useful to the creation of a multi-perspectivistic interspecies performing arts concept and practice.

Radically Green Theater

German theater scholar Hans-Thies Lehmann has described the performative endeavors of the Brazilian choreographer and director Maura Baiocchi as “one great research expedition into this terrain” which is “the major problem of our time,” namely “the relationship between the human being and its natural environment.”[1] From Lehmann’s point of view, the work of Baiocchi’s São Paulo-based Taanteatro Companhia

is nothing less than the ever-renewed attempt to promote a new “co-existence” of man and nature. In its performances, plants, animals, stones and water are situated on the same level as the human actor. It is a radically “green” theater that formulates a far-reaching critique of our civilization. In this regard, the reference to Antonin Artaud in several of the more recent works is anything but random.[2]

Taanteatro Companhia’s attempt of situating nature and the human species on the same performative plane implies, as mentioned by Lehmann, a critique of the dominating civilizational paradigm, designated as the Anthropocene, but also the attempt of a performative paradigm shift in conceptual and practical terms—to be described below—leading beyond the self-extinction scenario provoked by the human colonization of geological categories: a shift from an Anthropo-Scene to a Symbio-Scene through ecoperformance.[3]

Conceptual Web

As a performing arts concept and practice, ecoperformance emerged from Baiocchi’s artistic trajectory[4] and performing arts approach, named taanteatro[5] or choreographic theater of tensions. The work of Taanteatro Companhia ischaracterized by the interlacement of training, investigation, conceptualization, creation, presentation, production, and publication. In other words, ecoperformance is conceived in the realm of performing arts practitioners who also conceptualize their practice, not in a merely academic environment.

In systematic terms, ecopeformance intertwines with a conceptual web of previously developed notions—such as tension, ecorporeality, and schizopresence—only to be mentioned briefly in the present context.[6] In taanteatro, the premise of tension or the tension principle affirms the energetic interconnectedness of all phenomena in nature and culture. It operates as the non-discursive denominator of all elements composing a performance. Accordingly, ecorporeality denotes an amplified body concept holding that body and environment, including its diversity of life and existential forms, are mutual extensions. From a practical point of view, ecorporeality requires receptive and active awareness, not of the identity, but of the co-presence and mutual intertwining of the multiple forces and forms that generate, in their diversity but collectively, the emergence of a performative event. Finally, in taanteatro’s vocabulary, the word schizopresence designates this type of performative consciousness grounded in the elementary virtual level of performance, its tension flow.

From Ecoperformance to the International Ecoperformance Filmfestival

The notion of ecoperformance was introduced by Baiocchi around 2008/09 and integrated the presentation texts of DAN devir ancestral (DAN Ancestral Becoming).[7] This polymedia performance created in the Cerrrado region, a biome characteristic of the Center-East of Brazil, relied in its dramaturgic development not only on artistic concerns but also on the cooperation of environmental consultants and specialists in bioscience and zoology. The choreographer’s introductory note in the performance program booklet reads as follows:

DAN inaugurates the cycle of ecoperformances by Taanteatro Companhia. It elaborates the tensions between identity, the mestizo body, and the rich landscape of the Cerrado biome. By uniting my involuntary heritage (indigenous, African, European, and Asian) with the voluntary heritage of elective affinities acquired throughout my creative wanderings, I enact a corporeal becoming that scrambles the notion of the Self in time and space. Eco, from the Greek “oikos,” means house, the place where one lives. From the understanding of the body as an extension of the world and vice versa, inhabitant and house, body, and planet are confused. The constant attacks on animal, vegetable, and mineral life cause decay and death of bodies and cultures. Faced with the need for eco-ethical actions that aim at a careful interaction with all forms of existence, the ecoperformance DAN is a way to position me politically through artistic means.[8]

DAN premiered at the Bank of Brazil Culture Center in the Federal District of Brasília and toured in several Brazilian States until 2014. Conceived and presented as an outdoor installation and an out- and indoor performance, the visual dramaturgy of DAN included film projections, among them the cinematic triptych Ancestral Cerrado,[9] a composition of three interconnected films based on performances recorded in the astounding landscapes of the Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park as well as in degraded suburban areas surrounding Brasília, the capital of Brazil.

Following the premiere of DAN, Taanteatro Companhia developed projects aiming to amplify the discussion of ecoperformance as a form of political positioning by artistic means in favor of careful interaction with all forms of existence. Baiocchi’s need for eco-ethical actions took a performative shape in stage works, outdoor performances, the development of training techniques, and artistic residences. The widening of the conceptual debate about ecoperformance occurred between 2009 and 2019 via the Ecoperformance Forum held in Brazil and Argentina.[10] The forum program comprised testimonies, discussions, video screenings, and live performances, reaching out beyond Taanteatro’s artistic production by inviting performing artists, researchers, producers, journalists, and the audience in general to a broader scope of interactions about the relations between performance and ecology as well as a four-pillar perspective of performative sustainability (aesthetic, ecological, ethical, and economic). The company’s long-cultivated desire to situate the exchange of ideas about performing arts ecology within a mainly artistic setting finally came true in 2021, when the 1st International Ecoperformance Festival, held online as a part of the Taanteatro 30 Years commemorations, was announced as a project that,

in the face of the eco-political challenges of the 21st century, engages in the transcultural mission of gathering artists who perform in natural, urban, and virtual landscapes to poetically investigate, question, or reaffirm the co-presence, composition, and conflict of the body and the environment.[11]

On this occasion, and under the headline What is Ecoperformance?, the festival synthesized the concept of ecoperformance as follows:

Ecoperformance understands environment and body as inseparable dimensions of performative creation. In an ecoperformance, the environment constitutes a living and interactive play of presences and forces. The performer is not the central agent but one of the play’s components. At the same time that an ecoperformance experiments with environmental interactions as a performative event, it configures an environment process. Ecoperformance can happen in any landscape, natural or urban, and may, among other possibilities, question, honor, and reaffirm human being-environment interconnections. It may raise awareness of the harmful environmental impact of human actions and eventually become a vehicle of political denunciation.[12]

The inaugural edition of the festival received “proposals from five continents and selected 34 videos conceptualized [by the festival] as Ecopoet[h]ics and Ecopoet[h]ics in Progress.”[13] One year later, the number of submissions almost tripled while the festival itself was held online and in person.[14] According to the organizers,

the 2nd INTERNATIONAL ECOPERFORMANCE FESTIVAL intensifies its transcultural mission of bringing together transdisciplinary artists working in natural, urban, and virtual landscapes to investigate in an eco-poetic and eco-ethical way the tensions of conflict and composition between environment, body, memory, and ancestry.[15]

The first two editions of the festival presented approximately 80 films from about thirty countries. The interest in eco-performative practices and theory started to rise in cooperation with Brazilian and international artistic, cultural, and educational institutions, organizations, and events.[16] It manifested in articles, interviews, lectures, workshops, seminars, courses, and film screenings. Furthermore, with the cooperation of artists from the first festival, Taanteatro Companhia published the ebook Ecoperformance (2022), providing “the first more comprehensive publication concerning a relatively new concept and practice in the field of the performing and audiovisual arts.”[17]

Since the creation of DAN Ancestral Becoming, Baiocchi’s initial conceptual triangle—Cerrado biome, mestizo body, and Self—has undergone a gradual reformulation. The third edition of the festival, re-baptized as the International Ecoperformance Filmfestival, saw a further increase in submissions by artists from 40 countries. It declared the organizers’ attention to ongoing eco-political developments and rephrased key components of ecoperformance:

Encouraged by the eco-responsible approach of the new Brazilian government, the festival organizers expect considerable resonance of transdisciplinary proposals by artists exploring the tensions between environment, body, and ancestry in natural, urban, and virtual landscapes.[18]

Ecopolitics of the Affects

As mentioned, ecoperformance relates to a conceptual triangle—tension, ecorporeality, and schizopresence—whose terms emphasize the essential character of co-presence and the energetic connectedness of performative phenomena.

Ecorporeality, in particular, stresses the continuity between the body and its immediate local and distant cosmic environment and underlines the ecoperformers’ participation in open, hybrid, and interwoven social, biological, and geological orders and lineages, far beyond mere family relations. In a recent interview for the Environmental Dance project,[19] Baiocchi describes this evolutionary, spatial, and temporal extendedness of the body as follows:

The performer’s body is not a body aborted in nature. It was not born through a magic gesture, [but] comes from very ancient genes. It comes from ancestry, just as the planet earth comes from a universe that [is] infinite in terms of time and space, […] an ancestry not only related to a time that has passed, a time that is fading away, but also the ancestry that is projected from today to tomorrow, indefinitely.[20]

In other words, in ecoperformance, the concept of ancestry transcends even the human species by extending pan-energetic kinship to all organic and non-organic beings and forms of becoming, but, at the same time, because of its genetic-evolutionary, cosmological, social openness, it implies, beyond the discovery of heritage, the ethical and aesthetic challenge of creating a legacy. As Baiocchi puts it:

What, then, are the questions we must now ask? One of them is: What kind of ancestor do I want to become for my descendants? And together with this question comes another: What worlds do I want to build with my art, work, and life? These are questions that underlie ecoperformance. They are necessary. Otherwise, we run the risk of performing works still centered on the notion of anthrópos; works overly anthropocentric. We envision and crave a more expanded body. And this is where we arrive at the concept of ecorporeality, which proposes a body operating in networks, not isolated from other bodies, beings, and lives. We need to observe this not only in our artistic production but also in our daily life production. The performer needs to incorporate this notion of a body embraced by the environment, the world, the planet, and its circumstances, a body in constant tension with the things it relates to, and vice versa.[21]

Baiocchi’s expanded body is a “cosmonized” body, extending towards two infinities: micro and macro. But this expansion occurs precisely by being sensitized, touched, and transformed by the marvels and horrors of the physical and sensory world. Ecorporeality reminds us that the environment is not simply a territory of surroundings at our service, defined through and dominated by a human center, but a land- and life-scape endowed with sovereignty independent from us. It also reconfirms the biological wisdom defining the environment as the set of multiple, complex, and dynamic organic and non-organic conditions that make the existence and life of other beings on Earth possible.[22]

From a taanteatro point of view, all bodies and beings are environmental intersections constituted by, open to, connected with, dependent on, and different from other environments. Bodies are environments that inhabit environments together with other bodies, and are inhabited by environments that are inhabited by bodies and their interactions, and so forth. Thus, ecorporeality emphasizes the environment not as an external territory, property, or abstraction, but as the living world (Nature and its cultural products) in and around us.

Baiocchi’s critique of an all-too-human, anthropocentric performance paradigm,[23] labeled by her as Anthropo-Scene, goes hand in hand with the refusal of a biblical yet still-enduring idea, namely that all nature-immanent life forms converge towards their human lord, and that humanity converges transcendentally towards God (or other supernatural realities).

The political relevance and agenda of Baiocchi’s body-environment concepts become evident, at the latest, when the disastrous ecological, social, and economic results of authoritarian teleological ideologies hostile to nature can no longer be ignored given the existential threats and crises we are experiencing right now—in two words, climate change. The eco-extended body implies a politics of the affects:

All bodies, not just the human body, are producers of relationships. In taanteatro terms, we could say: producers of tensions. We aim for positive and propositional tensions: tensions that may reflect and improve the world. In our proposal, ecorporeality and ecoperformance combine in a policy of the body and the performer, the amplified body-performer, and of interrelated body-nature-world-circumstances-events. Not of that little thing over there: my little world, my art. This I that thinks of itself as the center of the world must rethink itself. It must try to evolve symbiotically with all other beings, all of life, and all the animate and inanimate beings that make our life possible. Without plants, without animals, without water, without the air we breathe, without the planet breathing well, without a happy planet, we also will be sad.[24]

Further political, ethical, and decolonial implications of ecoperformance, although not explicitly mentioned by Baiocchi, arise from the interrelationship between Earth and the body. Prior to private property, all bodies participated in the land as its natural extension. Since, from an ecorporeal point of view, the environment and the body are mutually coextensive, the practice of ownership and concentration of land and wealth deprives the “landless” or dispossessed populations not only of resources, but of their body itself and its natural and cosmic dimension.[25] In this sense, through the restitution of the environment to the body, ecoperformance exercises a symbolic cosmo-politics essentially opposed to colonization projects and their correlated monopolies of meaning maintained by the lords of all kinds of territories.[26] While anthropocentrism and property are associated with ethics of domination and exploration, ecorporeality points to symbiotic ethics.

Ecorporeal Ancestry

Subjacent to the joyful orientation of Baiocchi’s performance politics lies a pre-reflective sense and awareness of belonging and kinship that naturally implies, but reaches far beyond, our fellow human beings. Given that ecorporeality conceives bodies and environments as mutual extensions (even though not to the same degree), ecorporeal ancestry extends kinship to all organic and non-organic forms of nature. One may say that, in ecoperformance, bodies are always involved in a two-folded process of becoming: becoming-environment and, therefore, ancestral becoming.

Ecorporeal environment interactions simultaneously call for the receptive and active use of our senses and imagination. By directing sensory and imaginative attention towards the astounding diversity of beings (and their presence, qualities, expressions) populating the environment, our receptive faculties become active and our activity receptive. A place where maybe at first little or nothing seemed to happen begins to reveal, step by step, its unexpected atmospheres and life forms. Often, the impression of absence—of events or actions—indicates nothing but the non-activation of our body’s sensory levels and imaginative capacities. This is no surprise, given the conditioning and overstimulation of our receptivity span and spectrum in our daily lives and digital habits by a restricted but recurrent set of stimuli that tend to limit our perception of the very existence of phenomena as possible and valuable interaction partners. In regard to our culturally induced atrophy of sensibility, ecoperformance offers the opportunity for a fresh start by resensitizing the performers’ affective and visionary abilities through the bodily experience of environments and the experience of their bodies as environments.

The identity-challenging idea of the extended body expressed by ecoroporeality entails a differential perception of ancestry which, in its turn, amplifies the performer’s eco-ethical consciousness by comprising interrelationships and interactions with a variety of non-human and non-organic agents and by defying us to develop entirely new sets of human-non human communication practices and categories.

From a taanteatro perspective, the practice of ecoperformance depends on the “interpenetration between body and environment.”[27] As far as the performer is concerned, it requires a process of becoming-environment, in other words, a rite of transfiguration. This performative transfiguration relies, on the one hand, on the transcendental idea of the world (or environment) as a tension flow and, on the other, on performative body practices as tension converters. This approach, situated on a level prior to social symbolizations, allows for the energetic mediation between world and body and permits the performer to access the virtual ontological or Dyonisian plane of becoming-in-between underlyingperformance. From Baiocchi’s point of view, the consciousness of the necessity of becoming-environment already qualifies a performer as an ecoperformer:

Yes, it is possible to say that the performer dives into this attempt. It is the least a performer has to do: to try. Of course, we are not that tree. We are not the seawater, and the seawater is not us. But, poetically and artistically, anything is possible. Our imagination can produce the most diverse realities. This symbiosis of body and environment and the effort to become what you already are, needs at least to be attempted. A performer who incorporated this necessity is already an ecoperformer.[28]

Far from wishful thinking, mere declaration acts, and self-aggrandizing poses surrounded by impressive natural or urban landscapes, the attempt of becoming-environment is a transformative process of fine-tuning the performers’ poetic and shamanic sensibilities and faculties.[29] It demands the conceptual as well as practical overcoming of affective and cognitive dispositions, conditionings, and identity traits that define the performers’ social individuality—in other words: the symbolic death of the performer. As with all kinds of playful serious performing, this process may require the development of investigative trainings and protocols involving the immersion in and the sensory experience of life dynamics proper to the chosen environment: to inhabit a landscape without being guided by a preconceived, result-oriented program, to be inhabited by its interplay of forces and forms, and to perceive how these environmental dynamics affect us, not necessarily as acts intentionally directed at us, but through their unfamiliar communicative presence and in regard of their co-creative influence on a performance as a whole.

The co-evolutionary—symbiotically productive and shaping—interdependency between environment and body leads taanteatro to conceive them as inseparable dimensions of performative creation. Like an ecosystem, ecoperformance comprises a complexity of energetically, spatially, and temporally interrelated constituents (living or not) that depend on the system’s energy flow (or tension flow). The tension flow of a performance (not only ecoperformance) is determined by the presence, interactions, and expressive qualities of very different media, among which are a great variety of elements often and wrongly underestimated as passive, peripheral, ornamental, or supplementary in relation to human agents.

One may argue, however, and with good reason, that it is not the land, the sky, or the waters but us who declare certain events as performance, and that—given the preeminent conceptual and organizational role of human agents—the performing arts are by principle and exclusively anthropogenic and, in so far, also self-referential. So, what can it even mean to claim, as Lehmann does, that in the work of Taanteatro Companhia, “plants, animals, stones, and water are situated on the same level as the human actor”? Considering the difficulty of putting ourselves in somebody else’s shoes, isn’t this almost Copernican paradigm shift a mere fallacy? Are we humans not inevitably condemned to a maybe all-too-human anthropocentric perspective?

As the following considerations of Nietzsche’s perspectivism and Viveiros de Castro’s multi-perspectivism will hopefully demonstrate, self-referentiality is not an exclusively human privilege and not negative per se, but actually a shared trait of all beings and, up to a certain point, a necessary and entirely positive feature of self-awareness, self-affirmation, and self-realization in nature and culture. For these reasons, and from an eco-performative point of view, it is not necessary to define performance by the centrality of the human agent. The declared purpose of ecoperformance is not to deprive the performing arts of human actors, but—given the power, richness, and copresence of all kinds of performative life forces, as well as the compositional sensation and meaning generated by this copresence—to redimension their position and disposition within the performance. For ecoperformance, the human actor is one distinctive and important force among many, equally important and distinctive, forces that constitute the mediatic polyphony of performance.[30]

The recourse to the perspectivism of Nietzsche’s philosophy and Viveiros de Castro’s Amerindian anthropology may indicate how the variety of different perspectives that characterize every performative form of existence can be integrated and mediated in the context of the performance event, despite or perhaps precisely because of their respective singularity.

Nietzsche’s Perspectivism

“The Perspectivistic, [as] the basic condition of all life”[31] and the essence of knowledge is a recurrent topic of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophizing during his last creative decade.[32] According to Nietzsche, the essence of every living being (human and animal) arises from the encounter between organic conditions of existence and the being’s body, including its species-specific functional and perceptual forms, namely in the form of an epistemic perspective that generates a world peculiar to this being.

For Nietzsche, knowledge occurs following “the guideline of the body,”[33] “related to conditions of life,”[34] and “in the service of life,”[35] or, more precisely, of a specific life form. Each life form “of the organic world” comes with a “perspectivistic sphere,”[36] which is to be understood as the essential “perspectivistic inner multiplicity”[37] of an organic being, and which operates in favor of the selective egoism and struggle for self-preservation, growth, and self-awareness of this being; “in favor of his Will to Power”[38] and the interpretation of events in the form of “perspectivistic estimates by virtue of which we maintain ourselves in life.”[39] Since, according to Nietzsche, all forms of life and knowledge are self-referential and restricted to “a consideration from the corner,”[40] i.e., to a perspective without insight into the general purposes and course of the world, they are necessarily one-sided and unjust. Against the reduction of knowledge to purely anthropocentric models, Nietzsche concedes “that perhaps somewhere other interpretations than just human ones are possible,” given that “it is obvious that each being different from us feels different qualities and, consequently, lives in a different world than we live.”[41] In this way, Nietzsche’s philosophy opens up to the coexistence of multiple worlds and to the multiple interpretability of the world, respectively generated by different perspectives. However, he also underscores three anti-pluralistic elements:

- The thirst for domination of every drive for knowledge that “wants to impose” its perspective “as the norm on all other drives.”[42]

- The epistemic limitation of the mere appearance of knowledge, resulting from a species-specific perspective, within which man “cannot help but see himself beneath his perspectival forms and only through them.”[43]

- The falsification of our essentially singular and perspective-conditioned world experience as soon as “we translate it into consciousness”[44] and try to communicate it conceptually.

Amerindian Multi-Perspectivism

At first glance, Nietzsche’s thinking about body-environment relations and their key role in our existential, cognitive, and communicative potential may seem discouraging when it comes to the prospect of overcoming anthropocentric performance practices and conceptualizations. Nietzsche affirms the multiplicity of beings, worlds, and their interpretations. But he also denies the inter-communicability of perspective-specific experiences, not only between but also within species. As Nietzsche sees it, conscious communication never transmits our concrete perceptual experiences, only their conceptual generalizations and abstractions.

If the perspectives of all life forms are essentially self-centered, self-serving, and power-oriented, if we cannot even truly access the worlds of our immediate human neighbors, how can we then aspire to relate, interact, exchange, and communicate with non-human beings and actors? Can we earnestly attempt to overcome the Anthropo-Scene if our perspective as human beings is essentially and necessarily anthropocentric?

In response to these challenges, and recalling our considerations about ecorporeality, we may argue 1) that the human being exists and develops on an evolutionary continuum with other living and non-living beings, 2) that concept-based communication is only one form of interaction among a variety of others, and, therefore, 3) that the bodies and perspectives of different beings are indeed different but not entirely separated in their existence and lives on Earth. This differential inter-connectedness of life forms also might give us a clue as to how a philosophical unfolding of Nietzsche’s perspectivism, namely the Amerindian multi-perspectivism and one of its key aspects, the shamanic translation, can show us a way out of our monadic performative isolation.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s anti-colonial anthropology of immanence[45] is informed by Gilles Deleuze’s geophilosophy (which is, in turn, informed by Nietzsche) and reserves a privileged role for the shaman as a mediator of inter-species environmental experiences. The Brazilian anthropologist’s Amerindian multi-perspectivism attributes major social and (cosmo)political importance to the translation of shamanic experience for the indigenous community. The performative-narrative travelogue ritually following the shamans’ return from their schizophrenic journey mystically mediates their ecstatic experiences and processes of becoming in contact with non-human animal, plant, and mineral perspectives, and, at the same time, draws practical conclusions for community life.

Crucial to Viveiros de Castro’s anthropological endeavor—which claims conceptual affinity between indigenous metaphysics and Deleuzian philosophy (of Spinozist inspiration)—is its take on Amerindian human-nature relationships. In opposition to concepts based on human transcendence and superiority in relation to nature, indigenous thought regards man as immanent to nature and as different from, but on the same level as, other beings rather than as a difference of being. Amazonian thinking, says Viveiros de Castro, differs from Western anthropology in two fundamental respects: on the one hand, the reversal of the body-soul and nature-culture relationship; on the other, linguistically, the replacement of legal-theological codifications by an organically flowing, material, and sensory language.

Endowed with innate and interspecifically identical souls, all persons interpret the world from different perspectives due to the specificity of their bodies (to be created) in interaction with an environment. Based on the idea of a shared soul identity, multi-perspectivism holds that all beings “see (‘represent’) the world in the same way.”[46] “What changes is the world they see,”[47] as a result of the affect-based relationship of bodies (to be created) with their environment. Hence, Amerindian multi-perspectivism affirms that “the world [is] composed of a multiplicity of points of view”[48] constituted by the diversity of all existing beings (human, animal, spirit), each of them conceived as a person.

Following Nietzsche’s perspectivist self-referentiality, Viveiros de Castro’s multi-perspectivism maintains that each person (no matter the species) conceives her/himself as human and all other persons as non-human. Thus, the Amerindian conception of humanity is not based on metaphysical presuppositions regarding a specifically human substance or identity but refers to a person’s ontological potential to adopt a relational perspective, namely “the position of the cosmological subject.”[49]

Within Viveiros de Castro’s anthropology, the shaman’s journey can be described as a departure from the transcendent plane, described by Deleuze, of “a society’s organization of power”[50] towards the immanent plane of “individuating affective states of an anonymous force,”[51] that is, the unconscious of nature. For this reason, the body’s acquisition of its essence based on the interaction with the environment implies an increase of corporal manifoldness through composition processes with “a world that is increasingly wide and intense.”[52]

The ecstatic journey transports the shaman through ritual and symbolic death and the integration of different existential perspectives (by inhabiting them and being inhabited by them) to the realm of the recreation and reorientation of the affective faculties of the body.

Overcoming Nihilistic Perspectives

Nietzsche’s perspectivism, like Viveiros de Castro’s multi-perspectivism after him, starts from the diversity of perspectives constitutive of (the concept of) life. To Nietzsche, humans as well as animals are “complex formations of a relative life duration within becoming.”[53] Becoming, which “the means of expression of language are useless to express,”[54] is characterized by the absence of “enduring ultimate units, atoms, and monads.”[55] The concept of “unity,” the philosopher adds, “is not at all part of the nature of becoming,”[56] but was put into it, like the idea of being, “by us (for practical, useful perspective reasons).”[57] The assumption of units and things “serves our inseparable need for preservation” or, more precisely, the “preservation-intensification-conditions”[58] of human existences, which in turn are domination-structures or centers of domination characterized by multiplicity.[59] Life never exists in the singular, living diversity is the precondition of conceptual unity; this could be the formula summarizing Nietzsche’s thoughts in this context.

While Nietzsche’s perspectivism postulates the multiplicity of worlds and of the appreciative interpretations of all forms of life—in their specific being and their so-and-so acting and reacting—it also characterizes every being as a “power center—and not only man—[that] constructs the rest of the world by himself, i.e., measures, touches, shapes by his strength.”[60] This perspectivist constructiveness, however, manifests itself such that “each specific body strives to become master of the whole space and to expand its power (—its Will to Power:) and to push back everything that resists its expansion.”[61] Ultimately, it aims “at the preservation and increase in power of a particular animal species.”[62]

It is striking but by no means surprising that, at the beginning of high-level industrialization, Nietzsche paid little attention to the possibly fatal consequences of maximized anthropocentric power expansion—consequences that emerge apocalyptically today as a result of one hundred and fifty years of Anthropocene-Progress, and moved by an anthropogenic form of will to power turned totalitarian. In terms of the Deleuzian interpretation of Nietzsche, one may say that in the Anthropocene the negative and reactive form of will to power (or despotic desire) reaches the horizon of absolute negativity where it turns against itself and transmutes into the will to downfall by threatening to destroy the very conditions that make its existence possible—a will that contradicts life itself through the instrumentalization, standardization, and elimination of the diversity of life and by threatening the self-extinction of human perspectives through the industrial combustion of living nature. And all this despite good selfish reasons not only to tolerate the preservation of alternate perspectives but also to further them for the sake of self-preservation.

The apparent inevitability of being “every man for himself,” as the saying goes, or, in multi-perspective terms, of considering oneself “human” while all others are “non-human,” must not obscure the fact that closeness to oneself is only possible through closeness to others and the Other in the broadest possible sense. By institutionalizing its dominant patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting, the contemporary mega-urban lifestyle stops us from cultivating sensibilities that may otherwise allow us to accept and engage with flora, fauna, geo-, hydro-, and atmospherical elements as well as with other objects and events as possible and valuable interaction partners. Nature-unfriendly concepts combined with a lack of experience of nature provoke perceptual atrophy and lead to a vicious circle: the assumption that qualities that are not felt (anymore) simply do not exist and, therefore, do not require attention and the development of practices refining our interrelationships.

The translation of shamanic experience as discussed by Viveiros de Castro presupposes the existence and cultivation of a cultural receptivity that at least concedes the prospect of sensory and meaningful interspecies interactions. But the axioms of human transcendence of nature and the absolute non-communicability between perspective-related experiences remain irreconcilably opposed to an affective-cognitive openness and experimental willingness to, as Baiocchi puts it, at least attempt to develop performative encounters between human and non-human agents on operationally equal and nonetheless singular levels. In the face of a societal trajectory towards our own misery and downfall via the contempt for nature and nature in man, there are valid reasons for questioning those images, principles, theories, and practices that have led us so close to the abyss. This complex of misleading assumptions and procedures certainly includes those that claim or imply fundamental barriers between nature and human beings, thereby disqualifying human-nature interaction processes that do not restrict themselves to a purely logocentric understanding of communication (which cannot even fully account for interaction among humans).

At this point of a sensory and sensitive opening towards mediation dynamics that do not deny but transcend the element of informative, descriptive, and analytical language in favor of intensive transmissions, performers naturally come back into play and claim their place—and what is the shaman if not a multimedia performer, poet, and interspecies communication specialist?

Shaman, Mystic, Performer

A compelling manifestation of ecorporeal experience and ancestral awareness can be found in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The opening poem of Book I Inscriptions announces Whitman’s purpose under the title “One’s Self I Sing,” and in Book IV Autumn Rivulets he shares his cosmonized idea of the Self through the poem “There Was A Child Went Forth”:

There was a child went forth

And the first object he look’d upon, that object he became

And that object became part of him for the days or a certain part of the day

Or for many years or stretching cycles of years.[63]

Flowers, grass, birds, trees, fish, wild and domestic plants and animals, strangers and relatives, streets, houses, goods, vehicles, boats, rivers, mountains, the sky and the clouds: in Whitman’s vision, all “these became part of that child” and, by poetic transmission, they also “become of him or her that peruses them now.”[64] Whitman’s depiction of the mystical integration of reality in its differential entirety and with one’s own body can be extended from the visual to a generalized synaesthetic perception.

Far from rejecting rationalities and sciences that are friendly to Earth and Nature, the desire of departure from the Anthropocene and its Anthropo-Scene towards the Symbio-Scene requires the rediscovery and social cultivation of sensory receptivity, poetic imagination, and shamanic faculties, that is, a transformative type of empathy and interaction with all kinds of beings and becomings, something that may be called a mysticism of immanence.

For quite some time now, our life conditions have been under threat. And therefore, in retrospect, it does not come as a surprise that not so long ago in our civilizational development, the idea that “everything is connected” was capable of causing an almost revelationary impression, at least in occidental literary circles. Since then, the exaltation and marvel at cosmic entanglement has left its place to endless fears, worries, and denunciations of the past and its representatives. But instead of reiterating, day by day, in apocalyptic coloration, the intrinsic inescapability of our monadic perspectives, and capitalizing on the troubles and disasters to come, we should rather go beyond and invest more in depictions of possible futures, not in an a-critical fashion but in the mode of prophecy sustained and fulfilled by ideas and actions.

“The Theater Still Doesn’t Exist”

Antonin Artaud’s iconoclastic and energizing exclamation extolling the constant invention and reinvention of the performing arts holds for ecoperformance as well. There will never be a standard model for the (eco)performing arts, no masterpiece defining rule or form, but rather, always, a performative becoming regenerated by the new perspectives of upcoming agents within a critical-creative tradition.

Among the possible contributions of ecoperformance to the field of performing arts, its considerable capacity for dramaturgical innovation deserves attention. This potential—resulting from the integration and intermediation of perspectives, with their respective expressive resources, previously judged as irrelevant or incompatible—may enrich our concepts of socially relevant performative topics and forms or representation, and modify our notions of meaning.

Far from relegating human performers to a secondary plane, ecoperformance offers an immense experimental field of co-evolution with the molecular and and molar transformations of natural, urban, and virtual landscapes. Sometimes, the prefix eco- leads to the mistaken assumption that ecoperformance must occur “harmoniously” and exclusively in Nature. This assumption is inconsistent with both the creative and critical character of ecoperformance. In fact, the creative emergence of ecoperformance is due to a critical awareness of the historically problematic relation between nature and culture, between the body and its natural and cultural environments. Ecoperformance may occur in any environment. Despite its focus on body-environment relations and its symbiotic character, it may even focus entirely on the human body as long as it explores impersonal existential and expressive dimensions of bodies as environments.

Precisely this sort of research-expedition, as Lehmann put it, into the territory of unfamiliar body-environments and in interaction with their particular materialities, spatialities, and temporalities, opens up the prospect for the amplification and differentiation of the sensory, affective, and locomotive expressive faculties of performing artists. Given this creative openness, we may gladly echo Artaud, our ancestor: “Ecoperformance still does not exist.

Born in Duisburg, Germany, WOLFGANG PANNEK is the Director of the São Paulo-based Taanteatro Companhia, alongside the Brazilian choreographer Maura Baiocchi, with whom he is the co-author of several books, most recently Choreographic Theater of Tensions: Forces & Forms (2020). Wolfgang is also the Producer of the International Ecoperformance Filmfestival and holds an M.A. in philosophy, literature, and psychology.

dePICTions volume 3 (2023): Critical Ecologies

[1] Hans-Thies Lehmann, “A Radically ‘Green’ Theater,” in Maura Baiocchi and Wolfgang Pannek, eds., Choreographic Theater of Tensions: Forces & Forms, São Paulo: Transcultura, 2020, 8.

[2] Lehmann, “A Radically ‘Green’ Theater,” 8.

[3] For further information, see Wolfgang Pannek and Maura Baiocchi, “Towards a Symbio-Scene,” in WolfgangPannek, ed., Ecoperformance, São Paulo: Transcultura, 2022, 123-127.

[4] For further information, see my article, “Ecoperformance,” in Pannek, ed., Ecoperformance, 16-31.

[5] In order to distinguish between Taanteatro Companhia as performing arts company and the choreographic theater of tensions as its methodological and conceptual approach, we adopt the expression taanteatro (without capital T).

[6] A comprehensive overview of taanteatro concepts can be found in Maura Baiocchi and Wolfgang Pannek, “Dance of Concepts,” in Choreographic Theater of Tensions, 23-39.

[7] Videos of DAN Ancestral Becoming are available on Taanteatro Companhia’s Vimeo channel at these two links [14 April 2023].

[8] Excerpt from the program booklet of DAN Ancestral Becoming, São Paulo: Transcultura, 2010.

[9] A simplified version of the triptych Cerrado Ancestral is available on Taanteatro Companhia’s Vimeo channel at this link [14 April 2023].

[10] For further information, consult the blog of the Ecoperformance Forum and also on the site of Taanteatro’s [des]colonizações project [14 April 2023].

[11] Excerpt from the presentation text of the 1st International Ecoperformance Festival [14 April 2023].

[12] Excerpt from the International Ecoperformance Festival website [14 April 2023].

[13] Excerpt from the International Ecoperformance Festival website [12 April 2023].

[14] Since 2022, the International Ecoperformance Filmfestival has had a permanent partnership for in-person screenings with the São Paulo-based cinema Cine Satyros Bijou.

[15] Excerpt of the presentation text of the 2nd International Ecoperformance Festival [14 April 2023].

[16] Among these productive unfoldings around the concept and practice of ecoperformance are cooperations with performing arts departments at Brazilian and international universities such as State University of São Paulo (Unesp), State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Federal University of Goiás (UFG), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Khon Kaen University (Thailand), University of Toronto (Canada), Brown University (US), and The Oslo School of Architecture and Design (Norway).

[17] Wolfgang Pannek, “Editorial Note,” in Pannek, ed., Ecoperformance, 6.

[18] Excerpt from the International Ecoperformance Filmfestival website [5 March 2023].

[19] Environmental Dance is an online project by the Berlin-based Company Christoph Winkler [14 April 2023].

[20] Excerpt from Ecoperformance: Interview with Maura Baiocchi, International Ecoperformance Filmfestival YouTube channel, 6 February 2023 [14 April 2023], revised by Baiocchi.

[21] Excerpt from Ecoperformance: Interview with Maura Baiocchi.

[22] Thus, and above all, ecorporeality emphasizes environment neither as property nor as an abstraction, but as nature (and culture as nature’s product) and, therefore, as the living world that the human body, as well as any body, is part of, and that not only surrounds, but crosses and constitutes us.

[23] Our linguistic habits, as far as body-environment relations are concerned, tend to be self-referential. And to a certain extent, the human instrumentalization of nature and its reduction to a resource follow the same logic of linguistic hubris that reduces Welt (world) to Umwelt (environment). This may explain why Baiocchi moved from the label environment performance—which she employed in the late 1980s—to ecoperformance.

[24] Excerpt from Ecoperformance: Interview with Maura Baiocchi.

[25] Ownership of land entails ownership of its inhabitants. The land owner does not conceive himself as part of the property but as transcendent to it and as the master of its destiny. Everything existing within the property only has meaning in relation to the owner—the anthrópos—the central and personal union of law, surveillance, and punishment. Following this profaning logic, the dispossessed—human and non-human—no longer determine their existence or the meaning of their lives. To a society based on material and symbolic property, the mere existence of people not aiming at ownership constitutes a living objection, all too often considered worthy of oppression and even extinction.

[26] The relations between ecoperformance and decolonial thinking will be explored in an upcoming article for the performing arts magazine Arte da Cena, published by the Federal University of Goiás.

[27] Pannek, “Ecoperformance,” 28. The passage continues: “The body becomes landscape: natural landscape, cityscape, light-, color- and soundscape which, in turn, become part of the body.”

[28] Excerpt from Ecoperformance: Interview with Maura Baiocchi.

[29] Taanteatro Companhia has developed a series of such practices. For further information, see Maura Baiocchi and Wolfgang Pannek, “Mandala of Body Energy” and “Rite of the Shaman,” in Baiocchi and Pannek, eds., Choreographic Theater of Tensions, 43-58, 85-92.

[30] Even—or better, precisely—the identity between title and main character’s name in a classic tragedy like Hamlet makes it clear that the entire set of conflicts suffusing Denmark with a rotten smell also takes place in the young prince’s body, transforming it into a battlefield of power struggles and social degradation.

[31] Friedrich Nietzsche, JGB-Vorrede—Jenseits von Gut und Böse: Vorrede (Beyond Good and Evil: Foreword), first published 4 August 1886, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023]. All translations from Nietzsche are mine.

[32] Nietzsche’s confrontation with the epistemological problem of perspectivism occurred between 1880 and 1888. It permeated works such as Beyond Good and Evil; Human, All Too Human; The Gay Science; and the Posthumous Fragments.

[33]Friedrich Nietzsche, NF-1885,2 [91], Posthumous Fragments, Autumn 1885-Autumn 1886, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[34] Nietzsche, NF-1885,39 [13], Posthumous Fragments, August–September 1885, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[35] Nietzsche, NF-1884,26 [334], Posthumous Fragments, Summer-Autumn 1884, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[36] Nietzsche, NF-1885,43 [2], Posthumous Fragments, Autumn 1885, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[37] Nietzsche, NF-1885,1 [128], Posthumous Fragments, Autumn 1885-Spring 1886, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[38] Nietzsche, NF-1885,2 [108], Posthumous Fragments, Autumn 1885-Autumn 1886, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[39] Nietzsche, NF-1885,2 [108], Posthumous Fragments, Autumn 1885-Autumn 1886, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[40] Nietzsche, NF-1885,40 [14], Posthumous Fragments, August-September 1885, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[41] Nietzsche, NF-1886,6 [14], Posthumous Fragments, Summer 1886-Spring 1887, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[42] Nietzsche, NF-1886,7 [60], Posthumous Fragments, End 1886-Spring 1887, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[43] At best, Nietzsche concedes to man the ‘hopeless curiosity” of wanting to know “what other kinds of intellect and perspective there might exist.” Nietzsche, FW-374, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (The Gay Science), § 374, first published 24 June 1887, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[44] Nietzsche, FW-354, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, § 354, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[45] Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics: For a Post-structural Anthropology, trans. Peter Skafish, Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014.

[46] Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, 71, emphasis in original.

[47] Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, 71, emphasis in original.

[48] Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, 55.

[49] Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, 72.

[50] Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, trans. Robert Hurley, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1988, 128.

[51] Deleuze, Spinoza, 128.

[52] Deleuze, Spinoza, 126.

[53] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[54] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[55] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[56] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[57] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[58] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[59] Nietzsche, NF-1887,11 [73], Posthumous Fragments, November 1887-March 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[60] Nietzsche, NF-1888,14 [186], Posthumous Fragments, Spring 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[61] Nietzsche, NF-1888,14 [186], Posthumous Fragments, Spring 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[62] Nietzsche, NF-1888,14 [184], Posthumous Fragments, Spring 1888, Nietzsche Source: Digital Critical Edition [15 April 2023].

[63] Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, New York: Modern Library, 1950, 288-289.

[64] Whitman, Leaves of Grass, 289.

Responses