How Politics Shaped Ecology: A Conceptual Look at a Science of Relationships

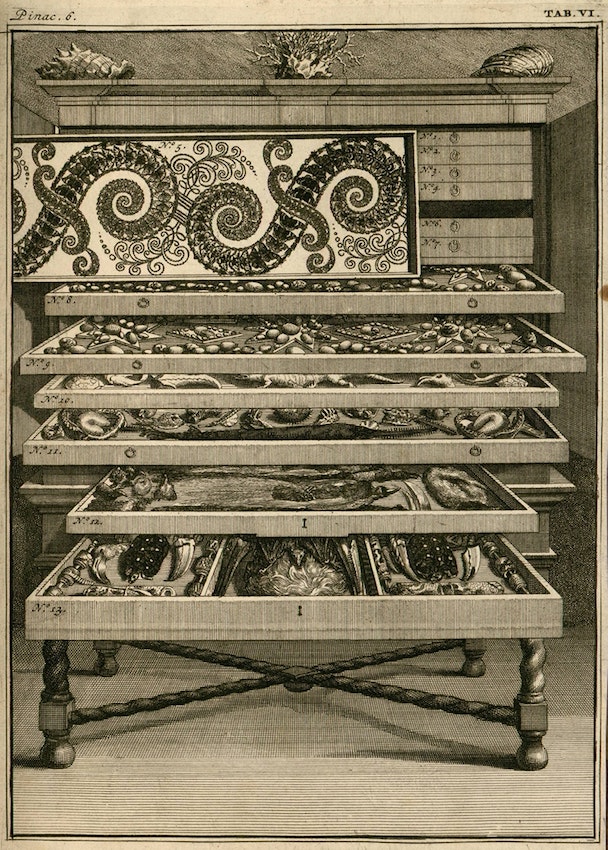

Image from Levinus Vincent, Wondertoneel der Nature (1706)

Jack Goldingham Newsom

How Politics Shaped Ecology: A Conceptual Look at a Science of Relationships

Ecology has taken as its object of study all the relationships that exist between and amongst living and non-living beings. Within the science, different concepts and methodologies have developed, some of which seek to justify political programmes—the very programmes which have led to the development of ecology in the first place. Thus, ecology is revealed to be a science of nature that is deeply social and political, with multiple competing paradigms at work. This insight, in turn, opens the way for new philosophical reflections.

Ecology as a discipline is inherently linked to the social and political movements of the time in which it is produced. This is because of its wide reach—studying both humans and natural relationships which do not involve humans—as well as questions of funding and the economic and political strategic objectives that ecology could fulfil. In the 21st century, many humans have come to terms with the fact that they are destroying ecosystems across the planet through their production and consumption decisions as well as the very economic and political motivations that originally led to the development of ecology as a science. I assert that if ecology is to become a science that helps human societies achieve radical systemic change, it needs to distance itself from current neoliberal, managerial, and cybernetic influences. Ecology must not be used to justify any political ideology based on the fact that its claims are intertwined with social and political imperatives. If ecology remains motivated by a desire to master and control nature, I strongly believe we will be unable to adequately confront the ecological crisis we are in.

This article looks at how ecology as a science has been influenced by social and political imperatives. It then discusses the epistemological underpinnings of these developments. Thirdly, an epistemological critique of ecology is proposed, drawing on the work of Georges Canguilhem. Finally, some possible avenues of critical thought are opened up to show how philosophical thinking can and must be done in this space.

The article focuses on what has happened in the scientific ecological movement, which has its proper set of premises and methodological challenges. It recognises from the outset, however, that many other approaches are possible in the relationship and understanding between humans and nature, especially the “ecologies” of indigenous peoples. These other methods should be understood on their own terms and could likely present similar openings for philosophical reflection.

The Beginnings of Ecology

The story of ecology begins with human beings in Europe and the United States noticing that their way of life was having an impact, never before seen, on the state of the planet and its ability to regenerate the resources they thought would always be present. This concern arose in the middle of the 19th century in most of the colonial powers of the Occident. During this period, the colonising empires were engaged in overseas voyages to conquer new lands with the aim of obtaining greater quantities of resources. From an economic point of view, they realised that if they wanted to pursue their industrial programmes and raise the living standards of their populations, they would require more resources than their territories could provide: the coal supply of England, for example, was small and finite. These powers were thus engaged both in a ‘race’ to develop their own empires at home and in the larger contest to control vast of human populations and natural terrains, including their flora and fauna, a contest that had begun many centuries before. In the process, explorers reported new plant and animal species that interested biologists in the colonial nations. Many biologists therefore left their homelands to collect and categorise these new species, bringing them back to the empire to create large botanical gardens.

In the middle of the 19th century, however, two changes occurred in the economic and political system, with the result that the focus of biology also changed and many new biological sub-disciplines were developed. As outlined by Yannick Mahrane in his article, “L’écologie: connaître et gouverner la nature,” the first change was a decline in the productivity of monoculture plantations such as wheat, corn, and sugar, which were beginning to lose their natural resistance to pests and weeds. The second change concerned the desires of politicians, who wanted to diversify and scientifically rationalise agricultural production in the colonies.[1] These two driving forces, most certainly linked, led to new research centres, laboratories, and greenhouses appearing in the United States and Europe so as to develop and grow tropical plants, find new methods to improve industrial agriculture, and feed these states’ growing populations.

The result was nothing less than a change in the ontological basis of biology as a science. Since Aristotle’s Metaphysics, we have mostly viewed the world as composed of different objects, individual and unlinked, each possessing an essence that makes them what they are. This objectification of the world that Aristotle named and brought about as a science and an ontology has allowed us to develop a mechanistic view of the world, develop technologies, and use these technologies to create machines, devices, and techniques; and has also allowed the sciences to develop to the extent they have today. Under this new political and economic imperative, however, biologists began looking not just at an apple as an object, but also at the tree, and the soil of the tree, the air around it, and the bees that pollinate its flowers. Instead of viewing the world in terms of separate and independent objects, biology began to look at all the relationships and the surrounding conditions of a particular object in order to understand it. Instead of seeing the plant in a field, it saw the landscape, the air, the climate, and the weather as factors that make up the plant itself. The organicist ontology at the origin of ecology was born, in opposition to a strictly mechanical physical science.

It was this change in viewpoint that was concretised by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 through the word “ecology.” Haeckel writes, “We mean by the term ecology the entire science of relations of the organism with the external world surrounding it, including, in a broader sense, all the ‘conditions of existence.’”[2] Dividing these conditions into organic and inorganic, Haeckel took the inorganic conditions to include physical and chemical properties such as light, heat, electricity, humidity, the availability of nutrients, and the state of the soil and water. The organic conditions included the ensemble of relationships with other living beings, whether supportive or destructive; for example, other beings that are eaten by an animal, and parasites that attack the same animal.

The framework, concepts, tools, and methodologies to study each of these relationships are completely different. For example, the instruments, criteria, and theoretical understanding that we use to study light sources for plants are unconnected to the way we study the threat that pests and small insects may present to the life of a particular plant. Despite these differences, ecology began to be taken up as an official scientific endeavour, as did the study of all these relationships from a variety of perspectives. The field of ecology developed in the decade following the publication of Haeckel’s work, with various contributions including the introduction of the word “biosphere” by Eduard Suess in 1875. The British Ecological Society, the first of its kind, was created in the United Kingdom in 1913.

The goal of the new ecological scientists, especially in the U.S., was not purely scientific: “these ecologists had the ambition to put ecology on the charts as the master discipline in the management and transfer of the natural resources of the United States.”[3] Ecology as a science was undertaking its research in order to understand nature and plant species in the United States, but also to realise the dream of the predominant discourse—humans as the masters of nature—a dream that, to this day, is far from realised. This form of ecology viewed nature and its resources as a system that worked according to particular rules and forms of regulation that existed a priori and could be determined by scientists and then manipulated so that human beings could shape their world as they liked.

The Second Phase of Ecology: A Natural Factory

The second phase of ecology began between the two World Wars, when ecology was institutionalised as a science about animals and plants. In this process, the militarisation and expanding reach of the capitalist and industrial economic system made the optimisation of autoregulating populations into the main subject of the field. Natural variations in population were modelled using statistical methods, thereby demonstrating, so ecologists believed, that these populations required a certain input of resources to sustain their growth, and that they had natural death and reproduction rates which could be exploited to obtain the maximal yield in cultivation.[4] Robert MacArthur’s research is emblematic of the ecology performed at this time, particularly with bird species such as warblers.[5] The growing militarisation of the West meant that military budgets and objectives started extending beyond the sphere of arms and national security. Defence departments began exploring how to secure food systems and, therefore, how to control and manage the many different life forms on their soil. The measurements performed by ecologists in different zones also began to include radioactivity, as a result of the development of nuclear technology.[6]

At the same time, a new metaphor began to take hold in the societies of the West—that of the factory, and the machine, originating from the Fordist economic vision in the United States: produce as much as possible at as low a cost as possible, through the use of machines and factories, in order to make larger profits. A similar trend is observable in the Soviet Union at the time, with science seen as a great modernising force for the economy.[7] Ecologists, nature, and the environment were not exempt from this visionary metaphor for the world. As many areas of society began to be viewed in terms of production processes, so did the populations of animals and plants that humans wanted to exploit for their own purposes. As Mahrane writes, “The science of ecosystems reconceptualises nature as an automated Fordist factory which works through inputs and outputs of energy and matter, organised around a standardised editing chain and a specialised division of labour.”[8] The most important measure of the performance of a particular ecosystem was the rate at which energy inputted into the system was convertible into biomass, and nature became a productive system subject to the same criteria of productivity as the labour market.

In ideological terms, these ecologists were optimistic, believing in technological solutions to the changes occurring in the ecosystems they were studying, changes of which they were increasingly aware. The idea was that better management based on better knowledge of the functioning of these systems would alleviate the errors that agriculturalists were committing, and thus halt the destruction of soils and the loss of different species. These researchers, many of whom were based at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in the United States, wanted to “transform ecology into a science of management of complex ecological systems and a tool to help public decisions.”[9] Whilst ecology was not yet a major topic in the public or political spheres, it remained a discipline with a political ideology underpinning its research programme: figure out how to better cultivate natural resources for the use of humankind, and develop technological solutions to avoid the negative externalities of this resource consumption. This statistical, quantitative, and rational approach to ecology has always viewed itself from within the social-political paradigm as contributing to the goals of the society at the time, removing the unknown and unpredictable from nature so that society could flourish.[10]

In the 1960s, ecology became an international challenge and movement. Between 1964 and 1974, a global project began to install observation stations around the world to measure the productive capacities of planet Earth. The rollout of this programme went in tandem with the creation of new departments of research in ecology at universities across the world. In the United States, the International Biological Programme had a budget of 43 million U.S. dollars between 1968 and 1974, and hoped to measure and predict environmental disasters and develop new technological solutions. Taking certain physical criteria as a starting point, models were developed to measure natural systems according to these criteria—a reductionist and deterministic approach that stood in contrast to more holistic approaches promoted by systems ecologists such as Eugene Odum at the University of Georgia. While the reductionist approach to ecology was criticised, it was also welcomed in many ecological circles because a variety and complementarity in approaches was seen as beneficial to the emerging discipline.[11]

The Third Phase: Ecology and Neoliberal Politics

As Western economies began to cement their liberal policies in the 1970s, ecology took another turn in its development. Following, once again, the economic policy and goals of the time, it began to view nature as a biosphere composed of different networks of ecosystems that are both complex and adaptative, and constantly subject to shocks (just as the economic system is subject to booms and busts). The states of equilibrium in an ecosystem, which previous ecologists tried to measure and which they took as a sign of the permanent state of the ecosystem, began to be viewed simply as transitory states, as results that would have changed had the observations been made at a different time. The deconstruction of models, social structures, and ways of life previously believed to be static and unchanging, along with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) and the 1972 Meadows Report (The Limits to Growth) further changed the attitudes of many ecologists.[12]

In the 1980s, a post-equilibrium approach was concretised as both ecologists and economists saw the faults of Keynesian large-scale economic management and similar notions of global equilibrium in ecology. Instead of maintaining equilibrium states “that permitted certainty, command, and control, [ecologists moved to] a ‘flux of nature’ paradigm focused on coping with uncertainty and complexity in dynamic and interconnected ecological systems.”[13] In line with the economic thinking of the time, Mahrane notes, “This new post-equilibrium ecology integrates perfectly in a logic that puts the accent on innovation, the flexibility of production processes and the decentralisation of management.”[14] One cannot miss the parallels between these terms and, say, the liberal politics of Emmanuel Macron in France as promoted during the most recent elections in 2022. Likewise, nature started being framed as a service provider, just like the company that provides our internet or the consulting companies that guide our governments. Nature, however, turns out to be a particularly difficult service provider because she is quite unpredictable and often goes against the wishes of her services’ consumers. To account for this difficulty, ecological thinking attempts to develop adaptative and flexible ways to manage nature.[15]

Just as in the 1930s the major metaphor for ecology was a closed system, a Fordist factory, also today, the influence of cybernetics and contemporary technology shows itself in ecological thinking. The natural machine is rejected in favour of the forest as a computer, a complex system network composed of multiple trees that each require air, oxygen, soil, and other resources, growing and perishing as part of interlinked and simultaneously occurring processes rather than independently of one another.[16] Different tasks are completed by different species, with different resources required to complete these tasks, and when we look at the ensemble of these tasks, we see the ecosystem functioning as a whole.

The Problem with Ecology: A Dominating Human-Nature Relationship

At the heart of ecological science still lies the implicit belief that human beings can control and govern nature: that they can step out of, and manage, a system of which they are a part. The goal of the prominent currents of ecology has always been to understand nature to such an extent that human beings can dominate and preside over it. And recent politics of environmental governance and environmental management, as exemplified by international climate change agreements and initiatives such as the 2004 European Environmental Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), still promote the idea that human beings can, in some way, gain a hold over the environment and nature, which can be manipulated, regulated, and controlled by human activity.

With each development in the history of the discipline, the presuppositions about who we are as human beings have also changed. In the first stage of ecology, the framework of the science was characterised by an organicist ontology. In the second stage, from 1945 to the 1970s, technological influences made ecologists view human beings in reductionist terms, following the idea of a computer or a machine. Like the human proposed by Thomas Hobbes and John Rawls in political theory, and Adam Smith in economics, cybernetic-influenced ecology proposes that the human being is a morally responsible yet strategic and calculating agent whose behaviour is constrained by the design of incentives and disincentives which make up the environment.[17] This results in political (and not only ecological/environmental) strategies that are authoritarian, moralising, and technocratic, based on the belief that if only governments and/or businesses could change the behaviour of individuals through carrot-and-stick techniques, they would be able to get themselves out of the crises they are in. This thinking has continued into the third stage, from the 1970s until today, despite the paradigm shift in the way nature is viewed, namely as a provider of ecosystem services that can be rendered to the benefit of human beings who require these services and must adapt to the changeable nature of the service provider (the Earth, the other living beings, etc). In this third stage, “human beings can control, and carefully use their own behaviours, attitudes and values to change their interactions with each other and the larger biophysical systems in which they are embedded.”[18]

Ecology, therefore, is intimately woven into the social and political goals of society. We must be aware of the fact that ecology does not present nature “as it is.” Rather, it has used dominant social and technological metaphors to represent that which seems to some to lie outside the category of humanity. These mechanistic metaphors are largely unable to explain the complexity and diversity present in nature. Whilst all models are to some extent false, because they simplify a natural phenomenon, we should still attempt to find ways of representing nature that are better able to account for what we know about it. As Jean-Paul Deléage has pointed out, ecology has now shifted its attention to the human-nature relationship. And although ecology by itself cannot remove or reduce the ecological crisis, it is crucial that we redefine the relationship between humans and nature in order to respond to this crisis. Philosophy and epistemology are the disciplines in which such a redefinition can take place.

An Alternative Viewpoint: Ecology as Historical Biology

What are the theoretical and conceptual alternatives to the current managerial environmental politics that is so prevalent in the 21st century, a politics that is largely ineffective and remains rooted in capitalist and neoliberal ideologies? For a philosophical critique of ecology from a historico-biological perspective, we can turn to the French philosopher of science, Georges Canguilhem, who has performed an epistemological study of the transfer of concepts between scientific disciplines, and between science and the social and political spheres. Canguilhem’s work brings into question many of the assumptions of the ecological sciences and can help us to elaborate another, more holistic kind of ecology, one that is not limited to the cybernetic analogies strongly criticised even within ecology itself.

One point of entry into Canguilhem’s critique is the concept of regulation. In an article on this concept, written for the Encyclopaedia Universalis in 1972, Canguilhem notes that regulation has a wide variety of meanings and uses in the fields of natural science, social science including economics, and also ecology and politics. The mechanistic form of the concept emerged from theological ideas. The regulation of nature is enabled either by a transcendent order that is given by a creator, God, or by a regularity of the conservation of constants that functions as a causal necessity. The finality of this order is also given either by God or because of natural laws. Within this mechano-theological conception, the order that we find here on Earth cannot be changed by living beings on the planet. According to physicists like Newton, only God can change the rules of regulation that he has set up. We arrive at this conclusion through a reductionist procedure: by cutting up the reality, we can see the necessary relations that conform to the rules.[19]

In the 21st century, the theological bases for this mechanistic concept have disappeared from much of social and scientific discourse. However, despite this, many people still think of a regulated nature according to laws that can be determined in a space where all the parameters are given in advance. For example, we continue with statistical modelling, sometimes believing the numbers we are calculating to be real representations of nature, not just models in a constructed set of circumstances. We think this way because we subscribe to the implicit idea that the world is regulated: every living being, every social system can be considered as regulated according to laws and norms established a priori.

To Canguilhem, any data we find that seems to show regularity, or a system in equilibrium, only demonstrates the state of disequilibrium of that system at a given time. In The Normal and the Pathological, he writes: “such analysis would not translate to a specific stable equilibrium, but the unstable equilibrium of norms and forms of life confronted momentarily and seen as approximately equal.”[20] The exception, then, is the rule, and imbalance is the norm in natural and biological systems. This approach criticises the very possibility of establishing ecology as a science of ecosystems in equilibrium, and a science of limits or boundaries that we can somehow violate according to certain uses of resources or pollution of environments.

The physical-mechanistic conception of regulation cannot account for the specificity of living beings and their plurality of normativities. But an alternative conception is enabled, Canguilhem maintains, by two new theoretical approaches: Darwin’s theory of evolution and the theories of the organism as developed by researchers like Kurt Goldstein. Canguilhem writes: “The characteristic of organic systems, unlike mineral structures, is their capacity for internal regulation.”[21] This means that the organism can develop its own norms and rules according to the conditions of the environment and its previous experiences. This creative capacity of the organism is always constrained by the material conditions of life, is therefore contingent upon these conditions, and cannot be established a priori. So, even without a theological underpinning such as God to guide the regulation of the planet, we can still say that regulation does exist somewhere in nature, namely within organisms themselves.

However, an issue arises when this idea of self-regulation is transposed to other fields of science, including the concept of the ecosystem, and thus modifies the way we see not only the organism, but all natural phenomena. Self-regulation makes sense in talking about organisms, but when applied to whole ecosystems, unanswered epistemological questions appear: Who is doing the regulating? According to what criteria are they regulating the ecosystem? It is exactly this point that Canguilhem criticises: the superposition of concepts across fields.

The example serves to demonstrate that the concepts taken as basic foundations in general considerations of ecology, such as ecosystem, equilibrium, and regulation, can be called into question. What, exactly, do these terms refer to, and according to which criteria can we establish any kind of norm, rule, or even system within the natural world? This resounding critique relativises ecologists’ claims regarding the earth and the biological world, and calls into question just how much we know about this immensely complex world that has developed its current structures over millions of years. We must beware of taking models as true or accurate representations of how things actually are. What is more, the predictive role that ecology has assumed, out of political necessity, rests on a theological-mechanical worldview that entails assuming a regularity and a certain baseline upon which predictions can be made. This is the same worldview that has led to the ecological problem in the first place.

Ecology Cannot Justify Our Political Decisions

How can we get out of this bind? And what does ecology as a science actually have to offer us? Canguilhem stresses the difference between the ecologist and the human being, the former with a task of research, the latter with a responsibility for his/her own life and the life of all others. In his article, “La Question de l’écologie : la technique ou la vie ?,”Canguilhem writes,

While making us aware of the biologically negative effects of the techniques and economy of the so-called developed societies, [ecology] tells us nothing—and has nothing to tell us—about the implicit or explicit choices that orient the decision-making powers. The political ideologies that claim to be based on ecology can only serve it by letting us believe that it supports them.[22]

We cannot, therefore, expect ecology to provide us with answers regarding climate change and our destruction of the environment. For example, ecology cannot tell us whether an emissions trading scheme (ETS) or replacing all petrol cars with electric ones will ‘fix’ the ecological crisis. Ecology can tell us it is in our interests to reduce our emissions: how we do such a thing, or whether we do it, is a consideration for politicians and citizens alike.

Ecology has, as its task, the attempt to understand more about the relationships between living beings. But the science itself is marked by a lack of clarity, with multiple, conflicting points of view, theoretical frameworks, and models vying for space. As Canguilhem notes, ecology opens a space in which philosophical thinking can engage in two tasks. The first is to recognise which questions need to be posed, so that ecology does not get lost in its own conceptual entanglements. The second is to watch and critique the transfer of concepts from and to the political space, such as regulation and equilibrium, which now define the neo-liberal economic paradigm. As we have seen above, a conceptual breakdown of the metaphors involved in ecology shows that science does not just present “facts about nature.” Political, social, and economic ideas influence our conception of nature, and our conception of nature influences our socio-political agendas.

In “La Question de l’écologie,” Canguilhem writes:

The term ecology currently designates an ideological amalgam. It ranges from liberal mea culpa to Marxist-Maoist anti-capitalism, from archaic naturism to hippie protest, from romanticism to regionalism. But ecology deserves better than ideological infatuation. This infatuation is moreover only the surface effect of a collective sensitivity to a question whose authentic place of formulation is philosophical thought.[23]

The question mentioned by Canguilhem concerns way that human beings inhabit the Earth, and the way they consider themselves as human beings. It is a uniquely philosophical question and cannot be answered by ecologists through their research. Rather, it must be addressed by philosophers, who work with concepts. Ecology opens a philosophical space by raising the question of relationship, be it between human and nature, nature and society, living being and other living beings, or human and world/earth. As a science, and not necessarily as a self-reflective discipline (despite the existence of reflective ecologists), ecology has shown the connection between human beings and biological systems, which, in turn, has brought into question many philosophical reflections of the last two millennia, the foundations of our societies, and the ways of life that we in developed societies practice. It is upon this fertile ground that political ecology can, and did, take shape. Canguilhem argues, however, that once this space has been opened by ecology, only philosophy can reflect on and present alternatives to the way we understand the relationship between humankind and nature. Ecology can tell us about the amount of human-produced plastic present in the soil, but it cannot represent to us, as beings seeking meaning in the world, what our relationship with nature is and should or could be like. It is philosophy, along with similar practices such as narrative and story-telling, that enables the generation of meaning.

I advocate for a tandem between ecology and philosophy in understanding the human-nature relationship. However, more radical views have been asserted. By some, including Cornelius Castoriadis, ecology is even considered to be non-scientific:

Ecology is essentially political, it is not “scientific.” Science is incapable, as a science, of setting its own limits or goals. If you ask it about the most efficient or economical ways to exterminate the earth’s population, it can (it must!) give you a scientific answer. As a science, it has absolutely nothing to say about the “good” or “bad” character of this project.[24]

Perhaps more so than other disciplines with a scientific ambition, ecology cannot separate itself from the human perspective. We cannot justify policy decisions using ecology because the discipline itself was built to serve our political desires. Ecological “results” or conclusions must be taken and interpreted with caution, especially when they are used to motivate or critique social systems. To blindly take ecological statistics to critique capitalism, say, is bound to fail because the very scientific basis upon which ecology rests is fragile and open to critique. At the same time, though, ecology is an immensely useful discipline in pointing us to the heart of the ecological problem itself: the relationship between living beings and, in particular, between human beings, other living beings, and the planet as a whole.

Aotearoa New Zealand-born thinker JACK GOLDINGHAM NEWSOM is currently conducting his PhD research in philosophy at Université Paris 8. His work focuses on political ecology: finding conceptual clarity amongst confused terminology and developing links between ecology as a science and the human project of reorienting our societies towards ecological futures.

dePICTions volume 3 (2023): Critical Ecologies

[1] Yannick Mahrane, “L’Écologie. Connaître et gouverner la nature,” in Dominique Pestre and Christophe Bonneuil, eds., Histoire des sciences et des savoirs, t. 3 : le siècle des technosciences, Paris: Seuil, 2015, 275-295, here 277.

[2] Ernst Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Allgemeine Grundzüge der organischen Formen-Wissenschaft, mechanisch begründet durch die von Charles Darwin reformirte Descendenz-Theorie, Berlin: G. Reimer, 1866, my translation.

[3] Mahrane, “L’Ecologie,” 282.

[4] Dean Bavington, “From Hunting Fish to Managing Populations: Fisheries Science and the Destruction of Newfoundland Cod Fisheries,” Science as Culture 19.4 (2010): 509-528.

[5] Robert H. MacArthur, “Population Ecology of Some Warblers of Northeastern Coniferous Forests,” Ecology 39.4 (1958): 599-619.

[6] Mahrane, “L’Ecologie,” 285.

[7] Jean-Paul Deléage, Une histoire de l’écologie, Paris: Seuil, 1994, 203.

[8] Mahrane, “L’Ecologie,” 284.

[9] Mahrane, “L’Ecologie,” 286.

[10] Stephen Bocking, “Ecosystems, Ecologists, and the Atom: Environmental Research at Oak Ridge National Laboratory,” Journal of the History of Biology 28.1 (1995): 1-47.

[11] Chungling Kwa, “Radiation Ecology, Systems Ecology and the Management of the Environment,” inMichael Shortland, ed., Science and Nature: Essays in the History of the Environmental Sciences, Oxford: British Society for the History of Science, 1993, 213-250, here 232.

[12] See Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, Boston: Houghton Miffin, 1962; Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens II, The Limits to Growth, New York: Universe Books, 1972.

[13] Dean Bavington, “Managerial Ecology and Its Discontents: Exploring the Complexities of Control, Careful Use and Coping in Resource and Environmental Management,” Environments 30.3 (2002): 3-21, here 3.

[14] Mahrane, “L’Ecologie,” 290.

[15] Jessica Dempsey, Enterprising Nature: Economics, Markets, and Finance in Global Biodiversity Politics, Oxford: Wiley, 2016.

[16] Daniel B. Botkin, The Moon in the Nautilus Shell: Discordant Harmonies Reconsidered, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, 158, 177.

[17] Bavington, “Managerial Ecology,” 10.

[18] Bavington, “Managerial Ecology,” 13.

[19] Georges Canguilhem, La Connaissance et la Vie, Paris: Hachette, 1962.

[20] Georges Canguilhem, Le Normale et le Pathologique, Paris:Presses Universitaires de France, 1966, 105.

[21] Georges Canguilhem, “La question de l’écologie : la technique ou la vie ?,” Dialogue, 22 (1974): 37-44.

[22] Canguilhem, “La question de l’écologie.”.

[23] Canguilhem, “La question de l’écologie.” 1974

[24] Cornelius Castoriadis, “La Force Révolutionnaire de l’écologie,” interview with Pascale Egré, in Cornelius Castoriadis, La Société à la dérive, Paris: Seuil, 2005, my translation.

Responses